We live in an era where reliable data has become an invaluable asset. We’re constantly bombarded with information from multiple sources, trying to grab our attention as quickly, effectively, and cheaply as possible. This has given rise to previously unheard phenomena that have been emerging over the past few years: anxiety-induced headlines & news fatigue, information overload, the surge of deepfakes, the perpetuation of clickbait culture, and many others. As we’ll explore, this trend has resulted in unstable confidence levels in traditional & non-traditional news sources.

This has allowed providers to search for alternative solutions; some examples include Ground News, NewsGuard, Full Fact, Snopes, and Media Bias/Fact Check. These platforms aim to provide news using techniques such as fact-checking, bias ratings, and source comparisons.

But despite this, the news platforms will cover only a portion of the whole picture. For example, discussing an increase in inflation without addressing underlying causes such as global market dynamics or monetary policies, covering natural disasters focusing solely on immediate impacts, without including root causes such as climate change driven by fossil fuel burning, or even highlighting technological advancements in the healthcare industry without considering the accessibility or affordability challenges for vulnerable groups.

This is precisely where this series, The State of Our World in 2024, comes into play. Throughout a collection of blog articles & guided projects, we’ll go over a detailed snapshot of our current global situation, attacking from multiple fronts:

- General Macroeconomics

- Industry & Trade

- Environmental Health

- Political Sociology

- Health and Well-Being

- Educational Development

- Demographic Trends

- Housing and Living Standards

- Social and Humanitarian Issues

- Private Sector

In this first Guided Project, we’ll explain the why and how of this series. We’ll start by discussing motivations, expectations, and a brief overview of the state of the news today. We’ll then define our document structure, provide a summary of measurement theory, & prepare our project using Python & R. Next, we’ll give a brief introduction to R for Data Science since it’ll be the main language for this series (an introduction to Python will also be provided when we get to the predictive methods sections).

Finally, we’ll start by building our country hierarchy from public databases. This framework will set the building blocks of all the analyses we’ll be performing throughout this series.

We’ll be using R scripts, which can be found in the Guided Project Repo.

About this series

For some time now, I’ve been thinking about the flood of news and opinions we’re exposed to daily. It’s a lot. Everywhere we turn, there’s talk about economic downturns, social upheavals, environmental crises, full-scale wars, or increased polarization. And if you’re anything like me, this constant flow of information can leave you feeling anxious (this phenomenon even has an appointed term called “headline stress disorder”, but more on this later). You want to be involved, but there’s too much going on.

Are things as bad as they sound? Are they better or worse? Are we getting the whole story or just fragments shaped by the loudest voices? Which sources of information are we consulting? Are they first-hand, second-hand, third-hand, or entirely made up? Are they government-based or private-based? Are they leaning towards a left stand, a center stand, or a right stand? Are we stuck inside a bubble of news provided by recommendation systems?

It turns out that ingesting information is a lot like ingesting food. Just as we can lean towards a balanced diet, we can also use reliable data sources and try to think critically whenever we’re presented with an opinion.

Over the last months, I’ve created a data repository filled with gigabytes of reliable data from credible sources – a quest that’s been daunting but also enlightening. What I’ve found is a wealth of organizations providing information that doesn’t often make it into the daily news cycle, data that can help us see beyond the headlines and draw our conclusions, and that is most frequently consulted by Economists or Statisticians when it should be readily accessible to the general public (yeah, some of these datasets hardly get past nine downloads…per month).

I’m not an Economist by any stretch; neither am I suggesting the unrealistic task of scrutinizing every news piece we get in our hands. I’m simply a Data Scientist who’s curious and looking for better ways to approach how we consume & interact with data.

This is why each week throughout the next couple of months, I’ll share my findings with you, examining different aspects of our world’s current state – not to add to the noise but to help us all make sense of it and hopefully gain some tools in the process.

What to expect

For those who have been following this blog for some time now, you’ll know that I like hands-on approaches, and this series will be no exception. We’ll not simply discuss results. Instead, we’ll go over each piece of code we use for analysis & visualization.

We’ll look at a lot of data from internationally renowned sources like The World Bank, UN, UNICEF, ILOSTAT, World Health Organization, and much more. I’ll be learning right alongside you, breaking down complex economic concepts into something slightly more digestible. I’ll always provide the raw data appropriately cited so you can always draw your own conclusions and use it however you want. I’ll also include all the second-hand resources I consulted throughout this process and found superb at complementing the primary sources.

We’ll also talk about data processing, statistical methods, visualization best practices, reporting best practices, and more.

The goal? To equip ourselves with better tools for critical analysis. To move beyond anxiety-inducing headlines and understand the broader context – historical patterns, global comparisons, underlying causes and effects, the credibility and biases of different sources, and all the details that shape a story.

For this series, we’ll mostly use R & RStudio; however, we’ll also include additional technologies such as Python for predictive methods, JupyterLab, VS Code & PowerBI for dynamic reporting.

The state of news today

How are people perceiving news today? How does this trust affect how people react toward national and worldwide conflicts? Which are the main sources of information consulted by people of different demographics?

1. Media Confidence

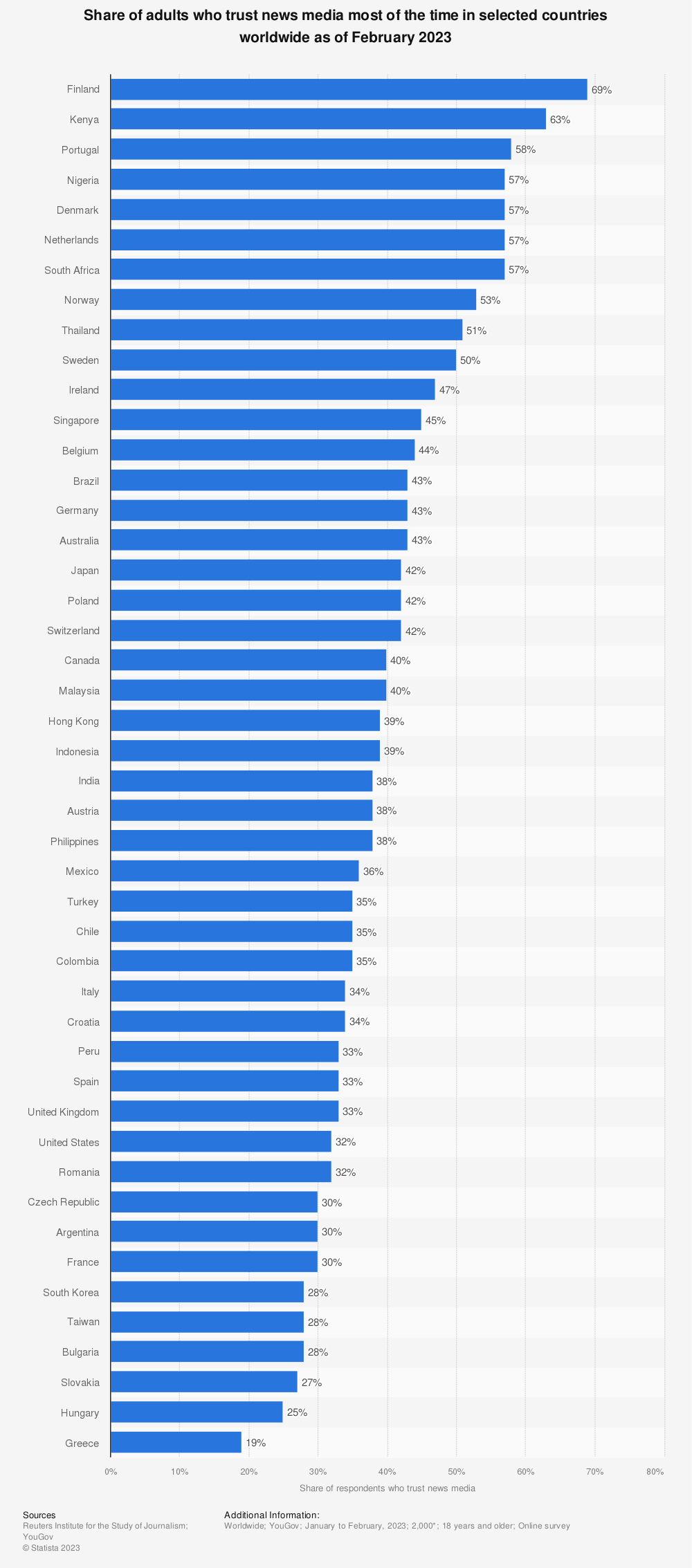

According to Reuters’ Institute for the Study of Journalism Digital News Report 2023, only 10 out of 46 countries have a share of adult trust in news media as of February 2023 above 50%. This means that 78.2% of the surveyed countries have a trust share below 50%:

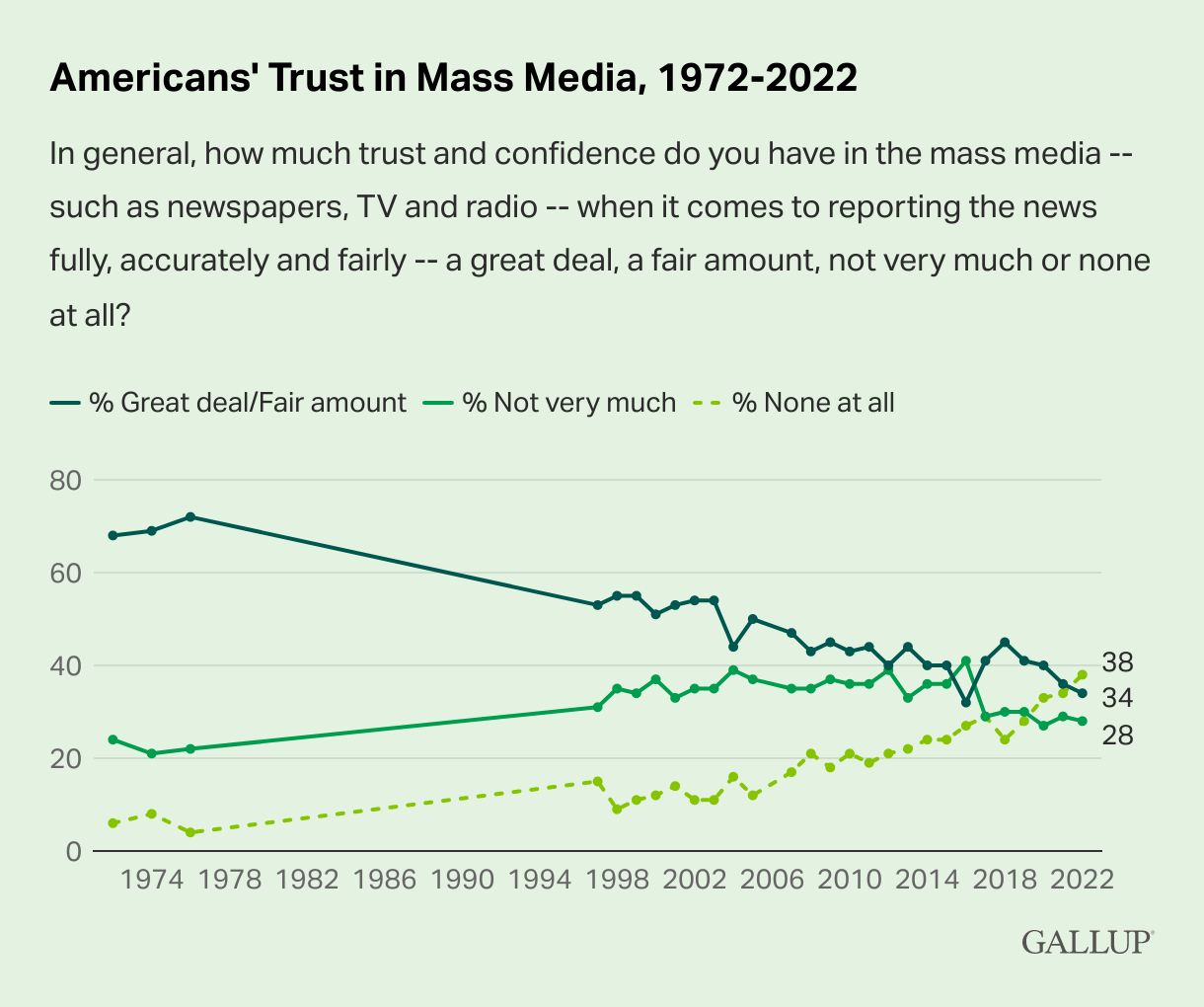

This can be due to multiple reasons and often depends on region-specific circumstances. For example, according to a 2022 Poll conducted by Gallup, the United States presented a significant decline in trust in media outlets during the time Donald Trump was in his presidential campaign, but has been showing a decline in high-trust levels (% Great deal/Fair amount) since the Poll’s first appearance in 1972:

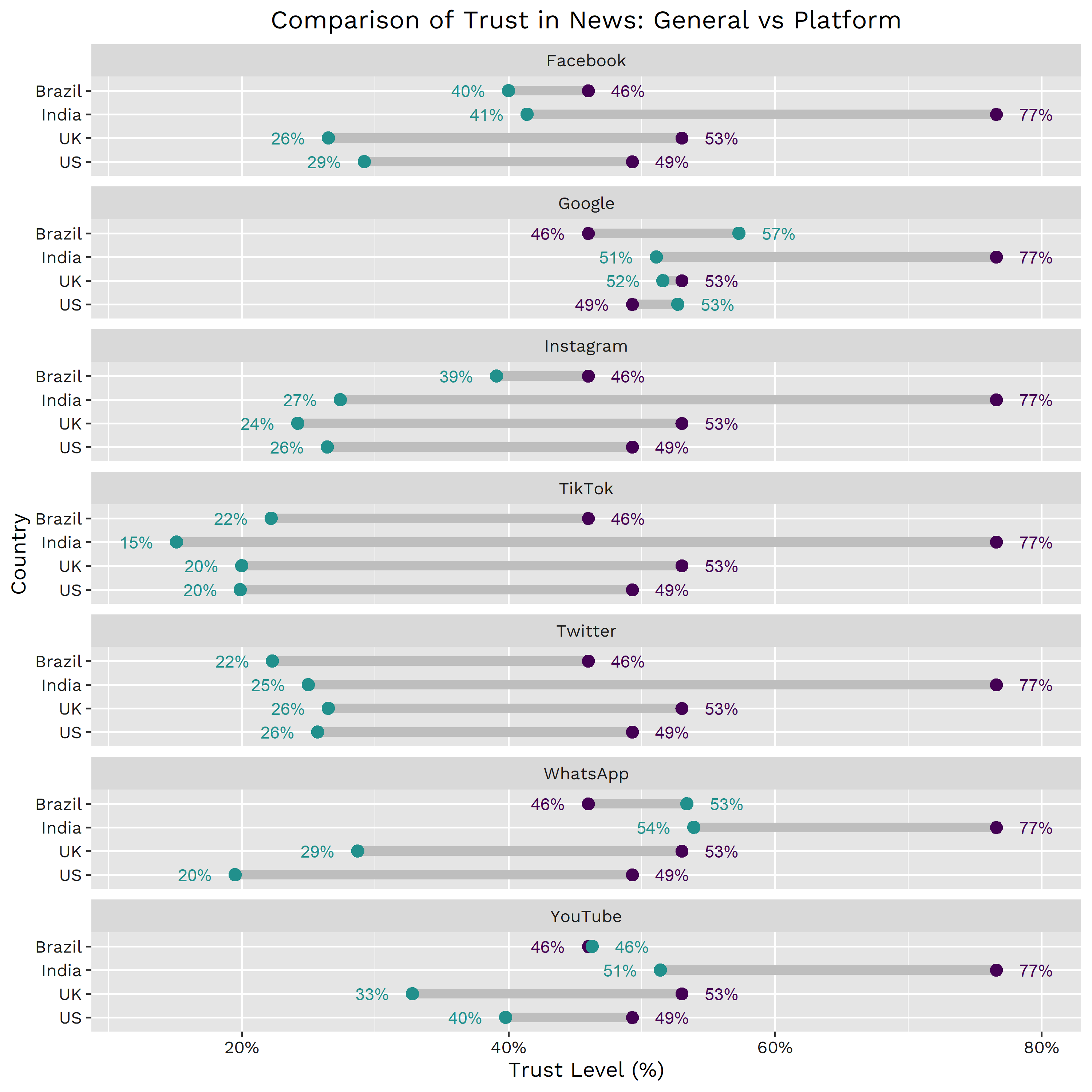

If we look at alternative platforms such as social media & search engines, we can see that according to the Reuters Institute, people in Brazil, India, the UK & the US still trust traditional news outlets more than social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, & Twitter (now X).

According to a study published by the Reuters Institute & the University of Oxford in 2022, the gap between trust in news on platforms vs. trust in news, in general, is significant for most of the platforms under study for the four economies. In general, people from these four countries tend to trust alternative sources, specifically social networks, less than traditional outlets (blue are news from platforms, purple are news from traditional outlets):

However, there are still some alternative news sources whose content is often not rigorously verified and whose gap vs. traditional news confidence is not that significant (i.e., people in the selected countries trust them more than traditional news outlets). One example is Google, which, according to Statista, perceived roughly 80% of its revenue from advertising in 2020 (the lowest since 2017). Another great example is YouTube falling under a similar scenario, where it’s publicly known that the majority of its revenue comes from advertising.

So now that we know a bit about how people perceive traditional & alternative news sources, how do people feel about misinformation as a perceived threat?

2. Misinformation

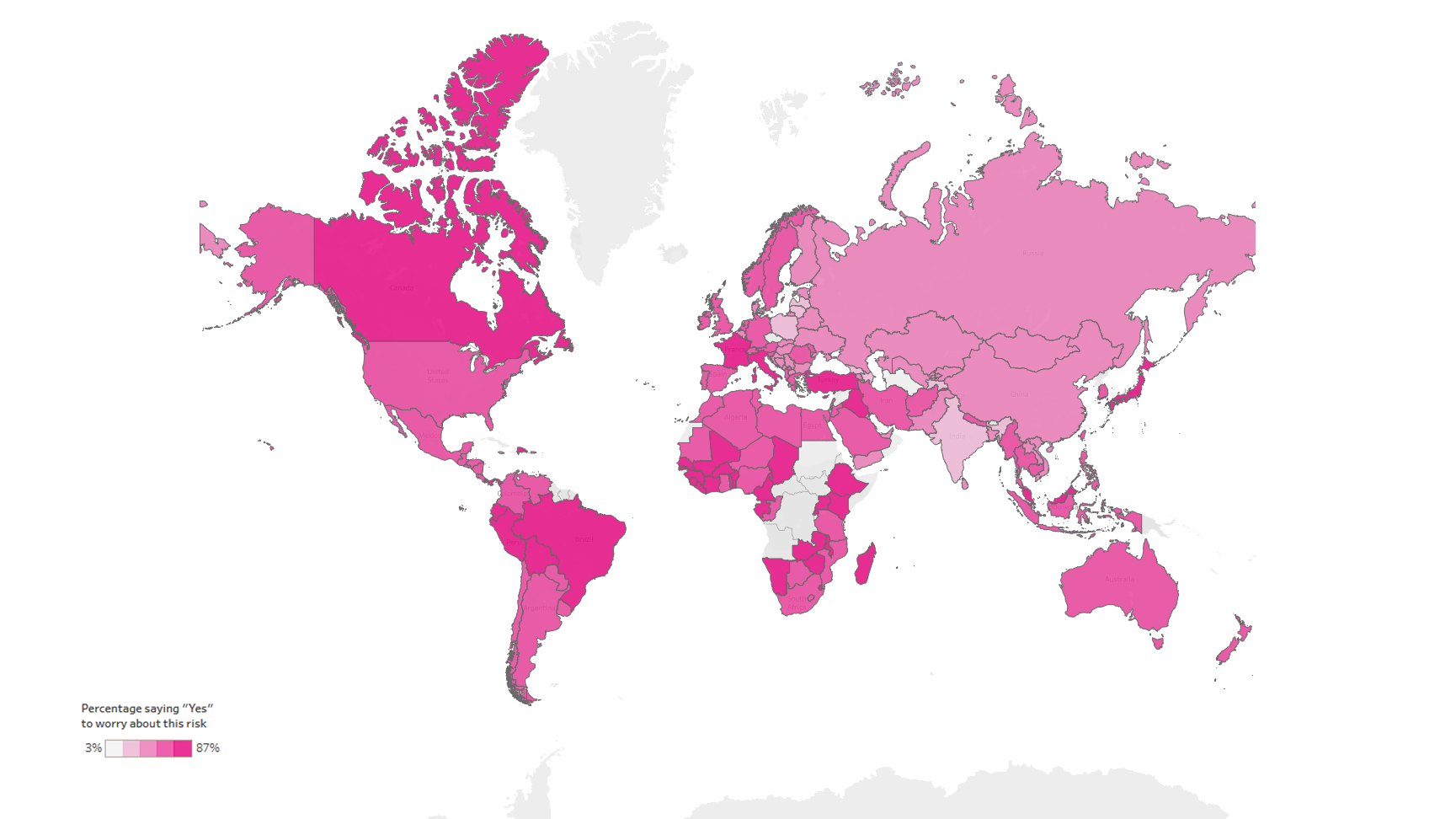

According to a study conducted by The Lloyd’s Register Foundation, 57% of internet users across all parts of the world, socioeconomic groups, and all ages regard false information, or “fake news“, as a major concern. According to the same study, concern is more prevalent in regions of high economic inequality and where ethnic, religious, or political polarization exists, leading to the weakening of social cohesion and trust. However, there is still a relevant number of developed countries with high percentages:

We can see that this figure reveals some regional patterns; people in Eastern Europe (46.9%, average) and Central Asia (38.1%, average) express low levels of concern. In contrast, Western and Northern Europe present higher numbers (64.5%, average). If we go to the Americas, we see that most countries stand out as regions where concern for misinformation is relatively high, particularly North America (67.4%, average) & the Caribbean Countries (74.2%, average).

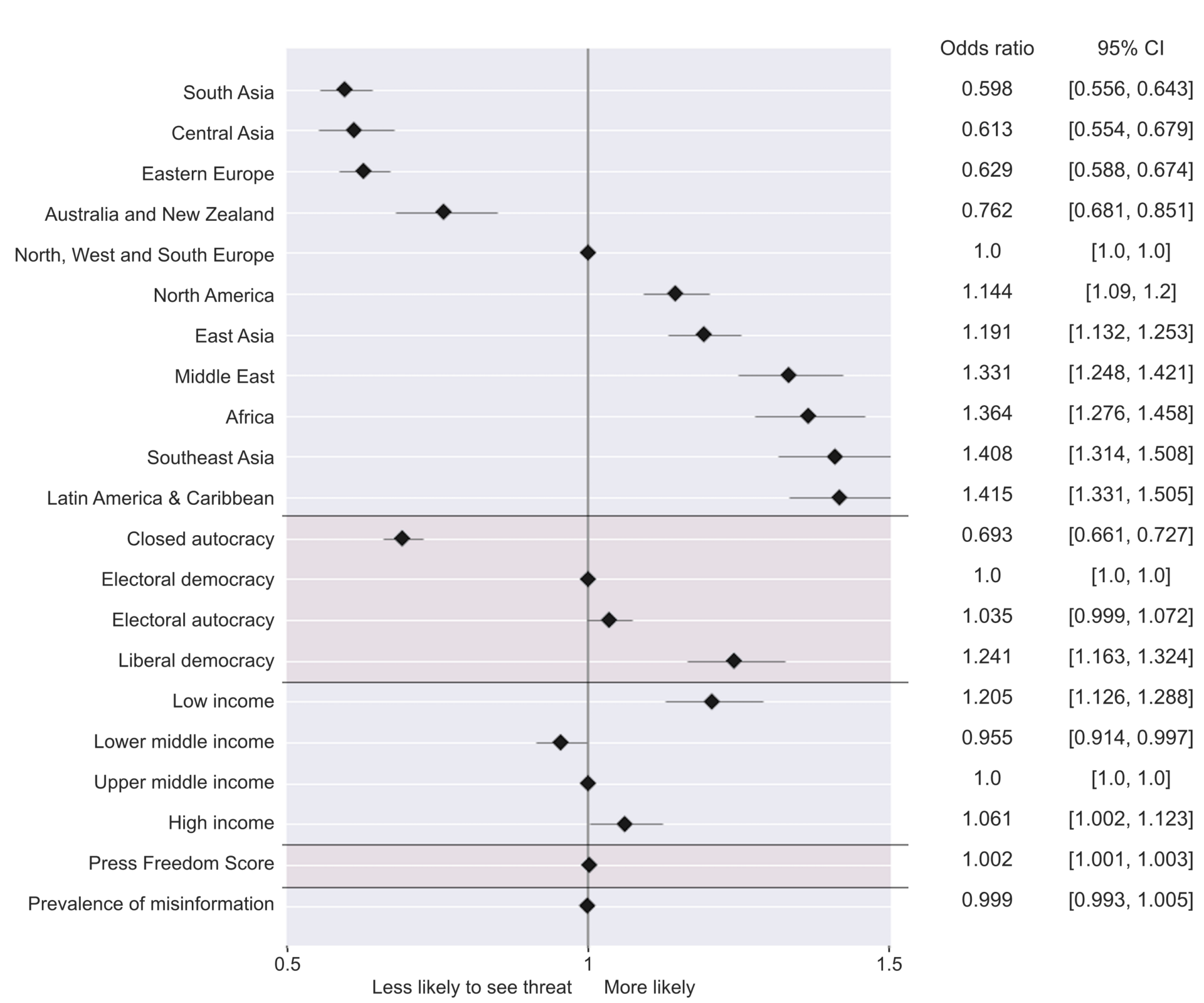

Interestingly, The Harvard Kennedy School also performed a country-level correlational study between variables found in the V-DEM dataset and the percentage of people who express concern regarding misinformation. They used a logistic regression model to model which variables predict risk perception of misinformation and published the results in their peer-reviewed article Who is afraid of fake news?:

From the figure above, we can suggest that:

- As discussed previously, there is a clear pattern when talking about regional-level likelihoods.

- Closed autocratic regions, where the media is mostly state-driven and strictly monitored, are less likely to express concern about misinformation. This can be due to the closed nature of autocratic governments and, thereby, the lack of exposure to international media. Also, fear of repercussions from the government when challenging the status quo is common and publicly known in these regions. These points are explored in more detail in the following sources:

- In contrast, electoral autocracies have a fairly higher percentage of likelihood, with liberal democracy having the highest.

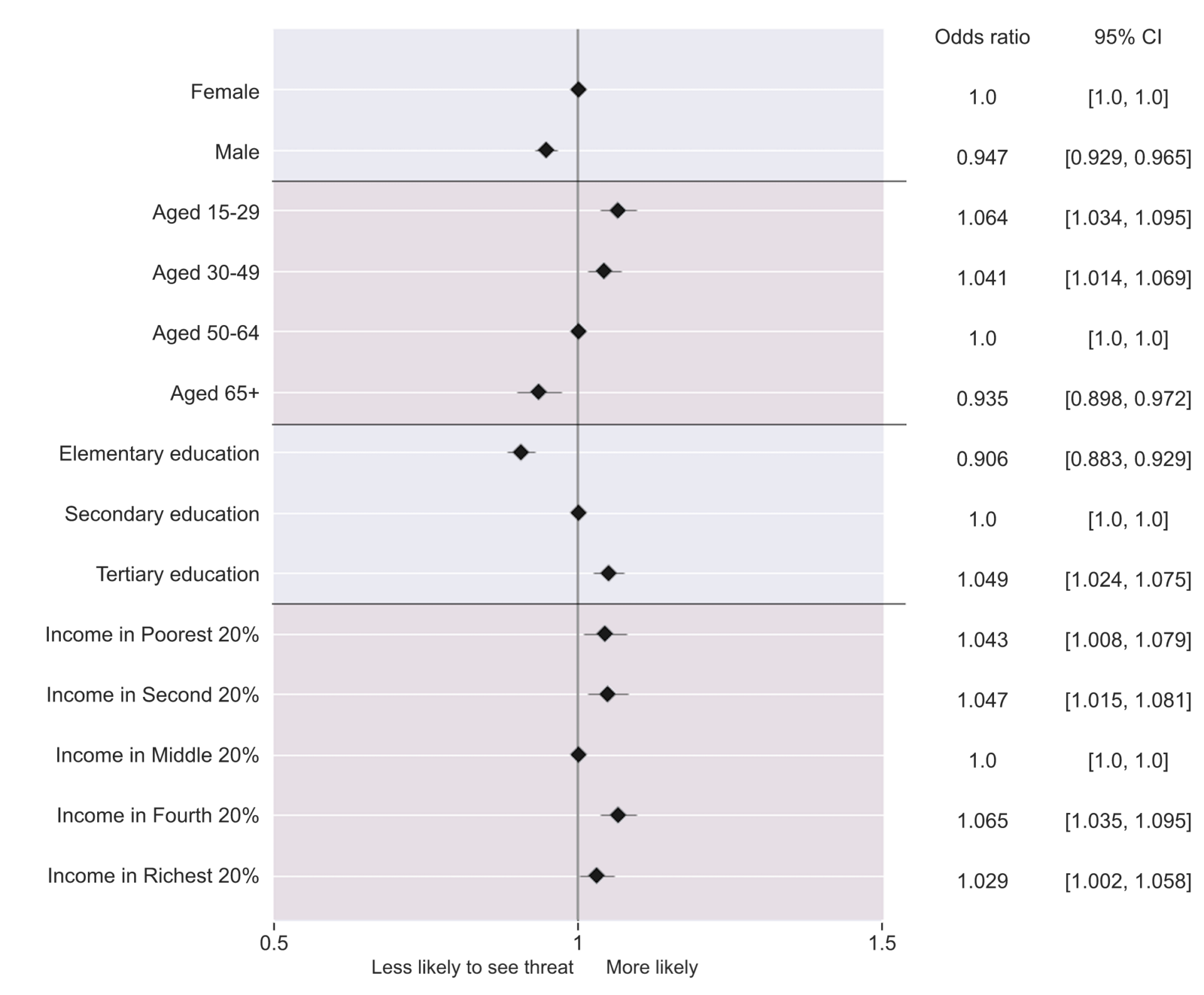

From the figure above, we can see that:

- Older people tend to express less concern about misinformation. This change is statistically significant and presents a clear trend from younger to older people.

- More educated people express more concern about misinformation. This is especially significant when examining the gap between Elementary and Secondary Education.

- Gender has a 5% gap, where females perceive more concern than men.

- Income levels are fairly similar, the only outlier being the middle-income group (above 40% & below 80%), which expresses less concern than the other income groups.

In short, misinformation appears to be a significant concern for a sufficient set of countries, and underlying patterns can help explain why this is happening.

So, what steps can we take to ensure the information we’re ingesting is reliable?

3. The QUIBBLE method

There are many journalistic practices we can adopt as everyday newsreaders; the most important ones can be summarized into what I call the QUIBBLE method (Questioning Underlying Information Before Believing, Learning, and Endorsing). You see, when we’re hit with news, the headline is often much more prevalent than the actual information contained in the article. This is mostly because “we live in a hypercompetitive world, and clickbait titles simply sell more news”.

Thus, when the data arrives, we already have a certain predisposition. This not only causes a potential bias but also affects people emotionally, as observed by Dr. Steven Stosny in his Washington Post opinion piece in 2017.

4. Breaking patterns

So, how can we bypass this initial reaction and focus on whether the piece is valid in the first place? There are some techniques we can (consciously) practice whenever we’re exposed to news articles and general information:

4.1 Verifying the primary source

- Ensure the primary source is credible and authoritative: This includes trusted authors, credible research institutions, and peer-reviewed material.

- Check if the sources are cited correctly, actually exist, and are accessible to the public: This one is a bit tricky since studies can sometimes reference data sources (most of the time, this happens for secondary sources) provided by organizations that require registration, that have paywalls, or that require an application procedure for us to be able to access the data. However, most socioeconomic data sources (public organizations such as The World Bank, ILOSTAT, OECD, IMF, etc.) are free for public consultation and even offer well-documented public APIs (some private organizations offer composite indexes or preprocessed data, and those can charge for subscription fees).

- Confirm that the data matches the information provided by the sources: Sometimes, the author may include a reference (by mistake or purposefully) that does not match the data being displayed. This can be caused by negligence, bad URLs, or even mistakes when writing the piece.

4.2 Understanding source bias and funding

- Research the inclinations or biases of the source: This is especially relevant since some news outlets can have mild to strong political inclinations and can even be partially or completely funded by governmental organs or for-profit private institutions. This is normal and does not necessarily mean that there will be a conflict of interest; however, we must consider balancing the sources we consult.

- Identify the funding behind the research or data collection: This helps uncover potential conflicts of interest. Of course, this is not always possible since private organizations can partially or fully fund public organizations (same as above, this is not always a problem. In fact, it’s sometimes beneficial since domain expertise is often required; the trick lies in simply knowing this fact before fully committing to an opinion). Common examples of this phenomenon include pharmaceutical companies funding medical studies and digital privacy studies funded by technology companies, among others.

4.3 Analyzing the metrics used

- Understand the metrics or indicators being used and how they are defined: Having at least a general notion of which metrics are being used to present conclusions is relevant since, for example, apparently similar metrics can have drastically different considerations or can even be measured in different units.

- Assess the appropriateness & validness of the metrics: A given metric might not be adequate for measuring given phenomena, and often, a single metric will not fully explain the real-world situation being described. This is why the study of socioeconomic, political, and environmental phenomena is often tackled from multiple angles.

4.4 Evaluating data collection methods

Examine how the data was collected and if there could be any errors in this process: Oftentimes, the authors will cite how the data was collected (e.g., surveys, experiments, administrative data), accompanied by the parameters of said collection. This is relevant when talking about surveys & polls; for example, incorrect sample sizes and unstratified sampling techniques under the wrong contexts can drastically skew the study’s outcome. This is especially detrimental if these considerations are withheld and not made known to the public when presenting the results.

4.5 Inspecting Data Visualization Techniques

I would argue that a big part of a misinformed opinion can come from incorrect visualization practices since it’s fairly easy to make mistakes or purposefully lie to the public using this technique; a simple change in the axis scales can completely transform how the audience perceives data. Below are a couple of nice resources with examples of what not to do when visualizing data:

- Misleading Graphs: Real Life Examples, Statistics How To

- Bad Data Visualizations, Real Life Examples Out There in the Wild, Tom Ellyatt

- Look at the types of visualizations (graphs, charts, maps) used to present the data: Not all visualizations fit all scenarios. There are several best practices are in place when selecting the most optimal visual object to show results. An excellent resource is the Best Practices for Data Visualization Guideline by the Royal Statistical Society.

- Assess whether the scales (linear, logarithmic) are appropriate and not misleading: This can be a major source of confusion since many data sources don’t even report the units they’re using. Another nice example widely found in line charts is what’s known as “exaggerated scaling“, where the minimum or maximum values of a given scale are exaggerated to reduce or increase apparent change.

- Ensure legends and labels are clear and accurate: As we mentioned, sometimes, a given axis might not have labels or units. This can cause misinterpretation or plain lack of understanding.

4.6 Checking for Data Consistency and Timeliness

- Ensure the data is consistent internally and with other credible sources: Socioeconomic data will often be reported by multiple sources, especially if we’re talking about relevant metrics such as GDP, Inflation, Consumer Price Index, Unemployment Rate, etc. The trickier part comes when the metric was designed by a single organization, the most common example being composite indexes (although other metrics are also included here). Composite indexes are metrics built from multiple indicators. Some composite index examples include:

- Confirm that the data is current or relevant to the time period being discussed: It’s sometimes hard to get up-to-date data, especially for the more airtight countries (e.g., closed autocracies, dictatorships), economies with ongoing political conflicts (e.g., recent coups, temporal governments), or economies with volatile political situations (e.g., once reported but stopped due to change in political regime). These cases are part of the bigger concept referred to as data holes. Some examples include Afghanistan, North Korea, Venezuela, and Syria. Moreover, some of these economies do not even belong to international reporting organizations such as the IMF, The World Bank, OECD, etc. This can create difficulties in gathering updated information, and if there is information but it’s outdated, it can tell a whole different story from the actual facts.

4.7 Reviewing Statistical Methods

- If a statistical analysis is included in the piece, check that said analysis is well-documented: Sometimes, the analyses used will be referenced from external research papers or created in-house and validated by a careful peer review process (this is the best scenario, but it’s not always possible). The most relevant organizations (ILOSTAT, The World Bank, IMF, etc.) will, most of the time, provide a detailed breakdown of their statistical methods as footnotes. They will sometimes be accompanied by considerations, assumptions & warnings for the method(s) in question. Examples include estimates for unknown data, sample design & collection techniques, predictive models, etc.

- Understand or at least have some notion of the statistical methods used to analyze the data: This is not always possible since some methods can be fairly technical. However, many authors often try to summarize the methods used in the executive summary or the body of the article. If in question, we can always make direct inquiries to the author(s).

- Check if the conclusions drawn are statistically valid and reasonably derived from the data: This is especially relevant since, as we have discussed, statistics is a powerful tool that can be used to mislead (purposefully or by ignorance) by using very simple descriptive statistics such as mean & standard deviation (e.g., skewness by outliers, scarce data points, etc.), to more complex methods such as estimators, hypothesis tests or predictive models (e.g., the underlying assumptions are not met, the results are cherry-picked, the model is overfit and can’t be generalized). In this series, we’ll learn to discern whether a given statistic makes sense under a given context and which statistics need the support of other statistics to get a more comprehensive picture (e.g., averages can often come with the count of observations, a quartile breakdown & the variance or standard deviation). We’ll also learn how to deal with assumptions, their importance, how to report if a given assumption for a given model is not met, and how to measure the implications of assumptions to our overall results.

5. It happens to everyone, really

As a Data Scientist, I’ve gone through countless occasions where the information had one or more of the slips abovementioned (I myself am guilty of this error). It’s easy to miss details, generate the wrong visualization, mess up the scales, use the wrong parameters for a statistical method, over-trust the source, and even come up with wrong conclusions due to lack of domain knowledge.

And this is fine since it’s all part of the process. What’s crucial is that we develop critical thinking in terms of how we consume & interpret information; we already know how data can be manipulated and that there are tools we can use to come up with better hypotheses & conclusions. What’s left now is practicing critical thinking again and again.

So, now that we know what to expect let us start preparing our project.

Document structure

Since we’ll be managing a lot of information & results, we’ll keep an organized structure throughout the article. Most of this will be extrapolated to the entire series. The framework will be as follows:

- Workspace setup using R & Python: We’ll use both languages throughout this series. We’ll use R for most data transformation operations, statistic methods, and visualizations. Python will be strongest when we start designing predictive models later in the series. We’ll create an R project & R & Python environments.

- A brief introduction to R: Since much of what we’ll do here will be related to reading & preprocessing data, designing statistical analyses, and designing & creating effective visualizations in R, we’ll invest some time discussing how this works.

- Statistical Analysis & Metrics Visualization: This will be the core of this series. We’ll mostly focus on visualizing data from multiple sources and perform statistical analyses if required. This section will be hierarchically divided as follows:

- Segments: Indicate the overall area of focus (e.g., Demographic Trends).

- Subjects: Indicate a more specific topic and contain a group of metrics (e.g., Immigration and Integration).

- Metrics: Indicate measurements used to track and assess the status of a specific process. As we’ll see soon, metrics can be classified into subgroups (e.g., Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX))

You can find a detailed breakdown of the Segments, Subjects, & Metrics here. I recommend that you use this document as a reference throughout the entire series since it’s organized sequentially. We’ll use the same order as the one in the document.

A word on metrics

Before diving deeper into the data, we must understand what a metric in this context is. A metric is a measure used to track and assess the status of a specific process. A metric can be classified depending on:

- If our metric is independent or depends on other metrics.

- If our metric measures a relationship between two numbers.

- If our metric shows an occurrence frequency and not a single event.

- If our metric measures the intensity of a given phenomenon.

We can try to group metrics based on these attributes:

- Indicator: Indicators are specific, observable, measurable attributes or changes representing a concept of interest. An example would be the poverty rate, which indicates the proportion of the population living below the national poverty line.

- Index: An index is a composite metric that aggregates and standardizes multiple indicators to provide an overall score. A well-known example is the Human Development Index (HDI), which combines indicators of life expectancy, education, and income to rank countries into levels of human development.

- Benchmark: Benchmarks are standard points of reference against which things may be compared or assessed. Some nice examples would be voter turnout rates or the number of women in political office compared to international averages.

- Ratio: A ratio is a quantitative relationship between two numbers, showing how often one value contains or is contained within the other. For example, the gender wage gap compares women’s and men’s median earnings.

- Rate: A rate is a special type of ratio showing the frequency of an occurrence in a defined population over a specific time period. For instance, literacy rates and crime rates are both frequency measures.

- Scale: Scales are used to measure the intensity or frequency of certain phenomena and often involve a range of values. The Air Quality Index (AQI), for example, measures the level of air pollution on a scale from 0 to 500.

- Survey Results: These are data collected directly from people, such as public opinion on government policies or satisfaction with public services.

Why is this important to understand? Whenever we hear about some metric in the news, we’re not always presented with how it’s calculated, which version is being used, what benchmarks are being considered, etc. This can quickly lead to misinformation. Below are some real examples:

- Reporting an unemployment rate without context, such as failing to explain whether they’re referring to the U-3 rate (the most commonly reported rate, which counts people without jobs who are actively seeking work) or the U-6 rate (which includes part-time workers who want but can’t find full-time work and people who have stopped looking for a job) can significantly alter the perceived state of the economy.

- Mentioning a literacy rate of 95% without understanding the appropriate benchmark (such as the average literacy rate for its region or income group) might completely bias the result towards a positive outcome when the real outcome, when benchmarked properly, might be extremely low.

- Interpreting a moderate score on an Air Quality Index (AQI) as “safe” without understanding the specific pollutants measured and their health impacts can lead to underestimating health risks.

- Comparing GDPs between countries without adjusting for Purchase Power Parity, or simply using Nominal GDP vs Real GDP without acknowledging that the first one includes an unadjusted inflationary component can lead to unfair comparisons and a worse or better perception of a given economy than how it’s doing.

- Taking survey results at face value without considering potential biases in the survey design or the sample’s representativeness can lead to incorrect conclusions about public opinion. This is extremely common and often happens around political contexts, specifically at political polling (this Medium article does a great job at explaining this phenomenon), where the sample is poorly designed, the results are poorly processed, the estimators are poorly created, etc.

The bottom line is that statistics is a very powerful tool that can be used to gather insights but also to mislead people, purposefully or by accident. Knowing how metrics are designed & built is already an extremely valuable tool we can use anytime Colgate decides to bring out a new advert on how good their product is.

Of course, knowing our metrics and their components & classification is just the first step. Throughout this series, we’ll try to explain every metric, including at least their most relevant properties & assumptions.

Preparing our workspace

After reading all my gibberish, the time has come to actually start doing something. We can begin by setting up our workspace. This will include:

- Setting up a folder structure.

- Setting up an R project and an R environment.

- Setting up a Python environment.

- Installing required packages for both parties.

1. Folder structure set up

We’ll set up a simple folder structure. Here’s what we’ll need:

- A

datafolder: This will contain all our input files.- With a subfolder for raw data for our extractions.

- With a subfolder for processed data for formatted, clean data.

- An

outputsfolder: This will contain all our results.- With a figures subfolder for all graphs & plots.

- With a results subfolder for all flat files & Excel sheets.

- A

srcfolder: This will contain our source code.- With a Python folder for the predictive model section.

- With an R folder for the preprocessing, analysis & visualization section.

- A

.gitignorefile: This will help us control tracking of specific files & folders from our repository.

Hence, the tree structure will look something as such:

Project Root

│

├── src

│ ├── R

│ │ └── scripts.R

│ │

│ ├── Python

│ │ ├── scripts.py

│ │ └── venv (Python virtual environment)

│ │

│ └── requirements.txt (Python package requirements)

│

├── data

│ ├── raw (Raw data files)

│ └── processed (Processed data files)

│

├── output

│ ├── figures (Generated figures, charts)

│ └── results (Results in CSV, Excel, etc.)

│

├── .Rproj (R Project file)

│

└── .gitignore (To exclude files/folders from Git)2. Environment set up

We can set up our environments once we have clarity on our project’s directory structure. We’ll start with R and then move on with Python.

2.1 R

Throughout this segment, we’ll mostly be using Posit’s RStudio Desktop. A detailed step-by-step installation tutorial can be found here.

We’ll set up two different components in R:

- An R Project: This will help us set up a working directory associated with our project. It includes an .Rproj file, which, when opened, sets the working directory to the location of this file and restores the session state. This will be useful for accessing inputs using relative paths and keeping everything tidy.

- An R Environment: This will help us manage R dependencies.

- Multiple R Scripts: These will be the core of our project. They will contain all the code we’ll use throughout this segment.

2.1.1 The R Project

We’ll start by creating our project. For this, we’ll use the Project Root directory we selected previously:

- Open RStudio.

- Go to

File>New Project. - Choose

Existing Directory. - Define the location chosen as the Project Root directory.

- Click

Create Project.

Depending on our Project Root directory name, we should have a new file with the .Rproj extension. This file works as a configuration file and sets the context for our project.

2.1.2 The R Environment

We’ll now create an R Environment specifically tailored for this project. From within RStudio, we’ll head to the R console and execute the following:

Code

install.packages("renv")This will install the renv package if we don’t have it already. We should get an output similar to the following:

Output

package ‘renv’ successfully unpacked and MD5 sums checkedOnce installed, we can activate our environment using the console:

Code

renv::init()If everything goes well, we should end up with the following new files & folders under our Project Root directory:

.Rprofile: This script runs automatically whenever you start an R session in a specific project or directory. It’s used to set project-specific options, like library paths, default CRAN mirrors, or any R code you want to run at the start of each session.renv.lock: This file is created by therenvpackage. It’s a lockfile that records the exact versions of R packages used in your project.renv: This is the folder containing our new environment, similar to what happens with Pythonvenvorvirtualenv.

2.1.3 Installing packages

For this series, we’ll need several R packages:

- Reading & writing:

readr: Provides the capability to read from comma-separated value (CSV) and tab-separated value (TSV) files. We’ll use this for reading mainly from csv files.readxl: Provides the capability to read Excel files, specifically tailored for well-known datasets (faster, uses more RAM, only analyzes the first 1000 rows to determine the column types). We’ll use this for reading datasets in Excel files.openxlsx: Provides the capability to read Excel files, specifically for big files with unknown values (does not have the first-1000-row-reading limitation). We’ll use this for reading from Excel files.writexl: Provides a zero-dependency data frame to.xlsxexporter based onlibxlsxwriter. Fast and no Java or Excel required. We’ll use this for our results exporting.arrow: Provides an interface to the ‘Arrow C++’ library. We’ll use this for reading & writing.parquetfiles, which we’ll explore once we get to the Machine Learning part of this series.

- Data manipulation:

dplyr: Data manipulation & complex transformations.tidyr: Changing the shape (pivoting) and hierarchy (nesting and ‘unnesting’) of a dataset by sticking to the tidy data framework: Each column is a variable, each row is an observation, and each cell contains a single value.data.table: Provides fast aggregation of large data, fast ordered joins, fast add/modify/delete of columns by group using no copies at all, list columns, and friendly and fast character-separated-value read/write. In short, a fasterdata.frameimplementation.stringr: Provides a cohesive set of functions designed to make working with strings as easy as possible.lubridate: Provides multiple methods for working easily with dates. This will be especially important in this series since we’ll deal with time series analyses often.purr: Provides various enhancements to R’s functional programming (FP) toolkit by providing a complete and consistent set of tools for working with functions and vectors.

- Statistical analysis:

car: Provides a set of common & advanced statistical functions. We’ll use this when we get to the statistical analysis part of this segment.broom: Summarizes key information about statistical objects in tidytibbles. This makes it easy to report results, create plots, and consistently work with large numbers of models at once.

- Data visualization:

ggplot2:ggplot2is a system for declaratively creating graphics based on The Grammar of Graphics. This will be our core data visualization package.ggalt: A compendium of new geometries, coordinate systems, statistical transformations, scales, and fonts for ggplot2. We’ll use this to complement our visualizations.RColorBrewer: Provides color schemes for maps (and other graphics) designed by Cynthia Brewer as described at ColorBrewer2. We’ll use this to create beautiful & consistent color maps.viridis: Provides color maps designed to improve graph readability for readers with common forms of color blindness and/or color vision deficiency. We’ll use this to complement the color maps provided byRColorBrewer.extrafont: Provides tools for using fonts other than the standard PostScript fonts. We’ll use this package to customize our visualizations.

Note: We’ll install the tidyverse package, which already includes the following:

ggplot2dplyrtidyrreadrtibblestringrpurrforcats

We’ll create our first R file inside our Project Root folder. In this file, we’ll declare the packages we’ll use. We’ll install them & import them. The script will be called setup_dependencies.R and will contain the following:

Code

# Define packages to install

required_packages <- c("tidyverse",

"readxl",

"openxlsx",

"arrow",

"writexl",

"data.table",

"car",

"broom",

"ggalt",

"RColorBrewer",

"extrafont",

"viridis")

for (package in required_packages) {

# We will check if the package is loaded (hence installed)

if (!require(package, character.only = TRUE)) {

install.packages(package)

}

}

# Snapshot the environment with renv

renv::snapshot()This file will behave as a dependency control file, where each time we need to change a specific package, we’ll be able to do so from here without having to manage dependencies from the analysis scripts we’ll be creating. For now, let us simply execute this script; all the packages should be installed in our environment, and the environment snapshot should be generated. This ensures that we freeze the package versions we will install now.

Now that R is set up, we can continue with Python.

2.2 Python

Similar to R, we’ll also create a Python virtual environment.

We’ll start by installing the virtualenv package:

Code

pip install virtualenvWe’ll then create our virtual environment using virtualenv:

Code

cd the-state-of-our-world-in-2024\src\Python; virtualenv venv --python='C:\Users\yourusername\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\python.exe'We’ll then create the requirements.txt for this project. We’ll include the following packages:

pandas: Provides data structures and operations for manipulating numerical tables and time series. We’ll use it as our main workhorse in Python for reading, transforming & writing data.numpy: Provides support for large, multi-dimensional arrays and matrices, along with a large collection of high-level mathematical functions to operate on these arrays. We’ll use this for several data transformation operations.openpyxl: Provides methods for reading & writing Excel files. We’ll use it to manage datasets that come in.xlsxformat and write results.scipy: Provides algorithms for optimization, integration, interpolation, eigenvalue problems, algebraic equations, differential equations, statistics and many other classes of problems. We’ll use it for a handful of applications, such as interpolating missing data and performing statistical computations along withstatsmodels,among others.matplotlib: Provides a huge set of methods for creating static, animated, and interactive visualizations. We’ll use this as our base package for creating plots in the ML segment of this series.seaborn: Provides a high-level interface for drawing attractive and informative statistical graphics. We’ll use it to complementmatplotlibwith visualizations.scikit-learn: Provides a set of simple and efficient tools for predictive data analysis. This library will be our workhorse for the ML part of this series.statsmodels: Provides classes and functions for the estimation of many different statistical models, as well as for conducting statistical tests, and statistical data exploration. We’ll use it for simpler statistical computations, although R will be our workhorse for this task.tensorflow: Provides several Machine Learning algorithms. We’ll use them when we get to the ML part of this series.ipykernel: Provides the IPython kernel for Jupyter. We’ll use it to create Jupyter notebooks later in this series.arrow: Provides an interface to the ‘Arrow C++’ library. We’ll use this to read & write Parquet files, which we’ll explore once we get to the Machine Learning part of this series.

pandas

numpy

xlsxwriter

scipy

matplotlib

seaborn

scikit-learn

statsmodels

tensorflow

ipykernelWe’ll finally install the requirements in our virtual environment:

Code

.\venv\Scripts\Activate.ps1; pip install -r requirements.txt; deactivateA brief introduction to R for Data Science

As we mentioned, this series will be heavily focused on reading & transforming data, producing descriptive statistics, designing statistical experiments, and creating visualizations using R. Because of this, we’ll quickly go over the basics in the context of Data Science. We will not go over the absolute basics of R since that is out of the scope of this series. However, a comprehensive beginner’s tutorial can be found here. You can skip to the Building the country hierarchy section if you’re familiar with R for Data Science.

1. What is R?

R is a dynamically typed functional programming language designed by statisticians for statisticians. Unlike languages such as Python, Java, or C++, R is not a general-purpose language. Instead, it’s a domain-specific language (DSL), meaning its functions and use are designed for a specific area of use or domain. In R’s case, that’s statistical computing and analysis.

So why R? Why not stick with Python if R is so specific?

Well, Python was not designed to be a statistical programming language; a good deal of the more advanced statistical methods are not available in the base packages or could even not be available at all. Even simpler, data visualization, a crucial component in scientific computing, is by far stronger in R with the implementation of ggplot2. Some might even argue that data transformation operations are easier & more intuitive in R, but that discussion is so tainted already that I’ll leave it for you to decide.

One thing is clear under our specific context: R excels at statistical computing & visualization, and Python excels at advanced Machine Learning algorithms. And if we combine both, we have practically everything we need to perform the following actions:

- Import data.

- Validate data.

- Transform & reshape data.

- Perform descriptive statistics.

- Implement advanced classical statistical methods.

- Implement advanced Machine Learning algorithms.

- Visualize our data.

2. Importing modules

Once we have a library installed, importing it in R is straightforward. We can use the library() function to import the library to our current project:

Code

library(tidyverse)This will make all tidyverse methods available to our session.

Let us load the following libraries we’ll be using for this introduction to R:

Code

# Load libraries

library(tidyverse)

library(readxl)

library(data.table)

library(ggalt)

library(RColorBrewer)

library(viridis)

library(car)3. An introduction to functions

Functions are key in maintaining our code modular, and they can save us a lot of time when preprocessing & transforming similar datasets. A function in R works similarly to a function in Python.

A function will:

- Accept zero or more inputs:

- Functions in R can be designed to take any number of inputs, known as arguments or parameters. These inputs can be mandatory or optional. Functions without inputs are also valid and often used for tasks that don’t require external data, like generating a specific sequence or value.

- Functions in R can also accept other functions as inputs, as we’ll see in a moment.

- Perform a given set of instructions:

- The function’s body contains a series of statements in R that perform the desired operations. This can include data manipulation, calculations, plotting, other function calls, etc. The complexity of these instructions can range from simple one-liners to extensive algorithms.

- Return zero or more outputs:

- An R function can return multiple values in various forms, such as a single value, a vector, a list, a data frame, or even another function. If a function doesn’t explicitly return a value using the

return()function, it will implicitly return the result of the last expression evaluated in its body. Functions intended for side effects, like plotting or printing to the console, might not return any meaningful value (implicitly returningNULL).

- An R function can return multiple values in various forms, such as a single value, a vector, a list, a data frame, or even another function. If a function doesn’t explicitly return a value using the

Additionally, R functions have features like:

- Scope: Variables created inside a function are local to that function unless explicitly defined as global.

- Default Arguments: Functions can have default values for some or all their arguments, making them optional.

- Lazy Evaluation: Arguments in R are lazily evaluated, meaning they are not computed until they are used inside the function.

- First-class Objects: Functions in R are first-class objects, meaning they can be treated like any other R object. They can be assigned to variables, passed as arguments to other functions, and even returned from other functions.

4. Declaring custom functions

We can declare custom functions in a similar fashion to what we would do in Python:

Code

# Declare a simple function with no arguments and a return statement

myfun_1 <- function() {

myvar_1 <- 1

myvar_2 <- 2

return(myvar_1 + myvar_2)

}

# Call function

myfun_1()

# Declare a simple function with arguments and a return statement

myfun_2 <- function(x, y, z) {

return(x * y * z)

}

# Call function

myfun_2(2, 3, 4)

# Declare a function accepting another function as argument and a return statement

inside_fun <- function(x, y) {

return(x * y)

}

outside_fun <- function(myfun, x, y) {

# Use inside fun

return(myfun(x, y))

}

outside_fun(inside_fun, 2, 4)Output

[1] 3

[1] 24

[1] 85. Reading data

In R, we can import data to our workspace by reading it from a physical file, using an API, or using one of the included R datasets. In our case, we’ll focus on reading data from existing files, specifically .csv, .xlsx, & .parquet files (the latter we’ll leave for later since we’ll not use it for the initial steps). Once we read a file in R, we can save our data in different data objects, depending on our requirements. There are three main data objects we’ll use in this series:

data.frame: They are tightly coupled collections of variables that share many of the properties of matrices and lists, used as the fundamental data structure by most of R’s modeling software.data.table: They are an enhanced version of adata.frameobject, the standard data structure for storing data inbaseR.tibble: Atibbleortbl_dfis an object based on thedata.frameobject, but with some improvements:- They don’t change variable names or types.

- They don’t do partial matching.

- Are stricter in terms of non-existing variables.

- Have an enhanced

print()method.

Some notes:

- A

data.tableobject is an extension of adata.frameobject. Hence, anydata.tableobject is also adata.frameobject. - This is relevant since, as we’ll see, many of the methods applying for

data.frameobjects are similar and sometimes equal to the ones to its enhanced version.

There are four main methods we’ll be using to read from the defined file types to the defined objects:

- Reading

.csvfiles intodata.frameobjects. - Reading

.csvfiles intodata.tableobjects. - Reading

.xlsxfiles intodata.frameobjects. - Reading

.xlsxfiles intodata.frameobjects and transforming them todata.tableobjects.

5.1 Reading csv files into data.frame objects

We can read csv files into data.frame objects using the following syntax:

Code

# Define directories

rDir <- "data/raw/"

wDir <- "outputs"Code

# Load data using read.csv (Dataframe)

df_csv_dataframe <- read.csv(file.path(rDir,

"GDP_Per_Capita",

"API_NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD_DS2_en_csv_v2_6011310.csv"))

# Check object type

class(df_csv_dataframe)Output

[1] "data.frame"5.2 Reading csv files into data.table objects

We can also read .csv files into data.table objects using the following syntax:

Code

# Load data using fread (data.table)

df_csv_datatable <- fread(file.path(rDir,

"GDP_Per_Capita",

"API_NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD_DS2_en_csv_v2_6011310.csv"),

header=TRUE)

# Check object type

class(df_csv_datatable)Output

[1] "data.table" "data.frame"5.3 Reading xlsx files

We can read .xlsx files into data.frame objects using the following syntax:

Code

# Load data using read_excel (Dataframe)

df_xlsx_dataframe <- read_excel(file.path(rDir,

"Drug-Related_Crimes",

"10.1._Drug_related_crimes.xlsx"),

sheet="Formal contact")

# Check object type

class(df_xlsx_dataframe)Output

[1] "tbl_df" "tbl" "data.frame"We can also transform our data.frame object to a data.table object using the following syntax:

Code

# Transform data.frame to data.table from excel-read file

df_xlsx_datatable <- as.data.table(df_xlsx_dataframe)

# Check object type

class(df_xlsx_datatable)Output

[1] "data.table" "data.frame"Once we have our data objects available, we can get information about our data and transform our objects using different operations.

6. An introduction to dplyr

dplyr is a package included in tidyverse, a collection of R packages specifically designed for data science-related tasks. In the words of the maintainers, dplyr is a grammar of data manipulation, providing a consistent set of verbs that help solve the most common data manipulation challenges (it’s important to mention that, while dplyr offers alternative methods for several base R implementations, it does not completely substitute it in most cases, so a hybrid approach is sometimes recommended):

mutate(): Adds new variables that are functions of existing variablesselect(): Picks variables based on their names.filter(): Picks cases based on their values.summarize(): Reduces multiple values down to a single summary.arrange(): Changes the ordering of the rows.

All of the operations above can be used with the group_by() method, which allows us to perform any operation “by group”.

Additionally, we also have the mutation join operations:

inner_join(): Returns matchedxrows.left_join(): Returns allxrows.right_join(): Returns matched ofxrows, followed by unmatchedyrows.full_join(): Returns allxrows, followed by unmatchedyrows.

Below are some key points regarding dplyr:

- It natively works with

data.frameobjects. - When possible, the data object will always be the first argument in any method.

- When possible, the output of a method will be a

data.frame. This allows us to pipe methods sequentially, as we’ll see in a minute.

6.1 The dplyr verbs

At its core, dplyr supports five verbs or transformations. We already mentioned them in the previous section, but here we’ll take a more detailed look at how to use them.

6.1.1 select()

select() will be responsible for transforming columns (variables) based on their names. With select() we can:

- Extract a column.

- Reorder columns.

- Rename columns.

- Remove columns.

6.1.2 filter()

filter() is used on a per-row basis to subset a data frame. With filter() we can:

- Remove

NaNvalues. - Filter by entry name on a given column.

- Filter by using comparison & logical operators.

- Filter by using other methods such as:

is.na()between()near()

- Filter by using our own functions for evaluation.

- And much more.

6.1.3 mutate()

mutate() is used to apply transformations to existing columns in our data frame. The result can then be saved to the original column or added as a new column to our data frame. With mutate() we can:

- Apply a mathematical function to an existing column.

- Assign a rank based on a given column’s values.

- Apply transformations using conditional constructs.

- And much more.

6.1.4 arrange()

arrange() is used to order the rows of a data frame by the values of selected columns.

6.1.5 summarize()

summarize() is used to perform summary statistics on a column basis. With summarize() we can:

- Get the mean of the values on a given column.

7. Data transformations & dplyr

dplyr is strongest in the data transformation area. We can combine verbs & methods to do practically most of the transformation & preprocessing work we need for this series. Let us now illustrate dplyr‘s capabilities with some hands-on examples.

7.1 Transformations using a single verb

We can start by illustrating how a transformation with a single verb can be defined:

Code

# Get a single column

metrics_2005 <- df_csv_dataframe %>%

select('X2005')

# Check head

head(metrics_2005)As we can see:

- We start by declaring a new variable called

metrics_2005, which will accept the computation results. - We then refer to the data frame object

df_csv_dataframe. This will be the starting point of our transformation. - We then use the

select()verb to extract a specific column. - Hence, the output will be the same type as the input, with only one column (

x2005) as the selected column. - Finally, we print the head of the object.

Output

X2005

1 36264.435

2 2635.508

3 1075.671

4 2780.209

5 4835.670

6 5865.291We can also remove NaN entries and add a new column that adds up all values on our single-column dataframe:

Code

# Filter NA

metrics_2005 <- metrics_2005 %>%

filter(!is.na(X2005))

# Mutate using arithmetic operations

metrics_2005 <- metrics_2005 %>%

mutate(sum_2005 = sum(X2005))

# Check head

head(metrics_2005)Output

X2005 sum_2005

1 36264.435 3341552

2 2635.508 3341552

3 1075.671 3341552

4 2780.209 3341552

5 4835.670 3341552

6 5865.291 3341552But wouldn’t it be nice to do this on a single expression? I mean, assigning & reassigning variables is tedious. Well, turns out dplyr has an implementation that solves this problem.

7.2 Transforming using multiple verbs (the pipe operator)

Complex data transformations using single expressions with dplyr can be achieved by using the pipe operator %>%. People with functional programming backgrounds and SQL users will find this approach very familiar; at its core, the pipe operator serves as an interface between one input and one output. It accepts one input and evaluates the next function with it:

... output input -> %>% -> output input -> %>% -> output ...So, in this way, the output of a function automatically becomes the input of another function without having to assign any intermediate variables.

Let us start by doing a three-step transformation using the pipe operator. We want to use the df_csv_dataframe to:

- Only select the base columns & latest year

- Remove

NaNentries for the latest year - Create an additional column that calculates the mean of the

X2022column.

Code

# Perform transfromation

df_2022 <- df_csv_dataframe %>%

select(c(Country.Name,

Country.Code,

Indicator.Name,

Indicator.Code,

X2022)) %>%

filter(!is.na(X2022)) %>%

mutate(mean_2022 = mean(X2022))Output

Country.Name Country.Code Indicator.Name Indicator.Code X2022 mean_2022

1 Africa Eastern and Southern AFE GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 4169.020 25187.34

2 Africa Western and Central AFW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 4798.435 25187.34

3 Angola AGO GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 6973.696 25187.34

4 Albania ALB GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 18551.716 25187.34

5 Arab World ARB GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 16913.653 25187.34

6 United Arab Emirates ARE GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 87729.191 25187.34Note that:

- We can break lines at the end of each pipe operator, making the expression highly readable.

- We can use vectors of column names inside

select().

7.3 Transforming using other functions

We can also pipe our data to other functions, such as:

unique(): Returns a vector, data frame or array like entry object but with duplicate elements/rows removed.count(): Returns an object of the same type as the entry object with the count of unique values of one or more variables.- Custom functions: We can declare a custom function and pass it as an argument in our chain of transformations.

- And much more

We can, for example, return the unique number of items from a specific column in our data.frame:

Code

# Perform additional operations

unique_codes <- df_csv_dataframe %>%

select(Country.Code) %>%

unique() %>%

arrange(desc(.))

# Check head

head(unique_codes)Note:

- We call

desc()with a dot.as an argument. The use of the dot.is a feature of thedplyrpackage, which acts as a placeholder for the data being passed through the pipeline. In short, we’re telling R “arrange the data in descending order based on the data itself“. Since the data at this point is just a single column, it effectively means “arrange the unique country codes in descending order“. This is extremely useful when we don’t want to rewrite the entire column name again.

Output

Country.Code

1 ZWE

2 ZMB

3 ZAF

4 YEM

5 XKX

6 WSMWe can even include the head() statement in the pipe sequence. This way, we get the top n items ordered alphabetically in descending order:

Code

# Get the top 10 items ordered alphabetically on descending order

unique_codes_head <- df_csv_dataframe %>%

select(Country.Code) %>%

unique() %>%

arrange(desc(.)) %>%

head(., 10)

# Check object

unique_codes_headOutput

Country.Code

1 ZWE

2 ZMB

3 ZAF

4 YEM

5 XKX

6 WSM

7 WLD

8 VUT

9 VNM

10 VIR7.4 Calculating aggregations

Aggregations are a key aspect of data analysis & data science. They let us look at summarized version(s) of the data when we have, for example, a variable that we wish to group by. Having said this, we also need to be careful when summarizing data; some metrics cannot be directly summarized due to the nature of their calculation. We have three main scenarios where this can happen:

- The calculation is arithmetically or statistically incorrect.

- The calculation is arithmetically or statistically correct, but the metric should not undertake the given calculation since it changes its meaning.

- The calculation is both arithmetically or statistically & contextually incorrect.

For example:

- Averaging Averages in Income Levels: Suppose we have average income data for multiple cities in a country. A common mistake is calculating the national average income by simply averaging these city averages. This method is incorrect because it doesn’t account for the population size in each city. The correct approach consists of using a weighted average, where each city’s average income is weighted by its population.

- Summing up Rates or Percentages: Let’s say we have unemployment rates for different age groups within a region. Summing these rates to get a total unemployment rate for the region is a mistake. Rates and percentages should not be added directly because they are proportions of different population sizes. The correct method is to calculate the overall rate based on the total number of unemployed individuals and the total labor force size.

- Aggregating Median Values: Median values represent the middle point in a data set. It will be statistically incorrect if we have median income data for several groups and try to calculate an overall median by averaging these medians. The median should be calculated from the entire data set, not by averaging individual medians.

- Mean of Ratios vs. Ratio of Means: This mistake occurs when dealing with ratios, like debt-to-income ratios. Averaging individual ratios (e.g., averaging debt-to-income ratios of several households) can give a different result than calculating the ratio of the means (total debt divided by total income of all households). Each method has its own interpretation and use, and using one instead of the other can lead to incorrect conclusions.

These are just some common examples, but the point is made.

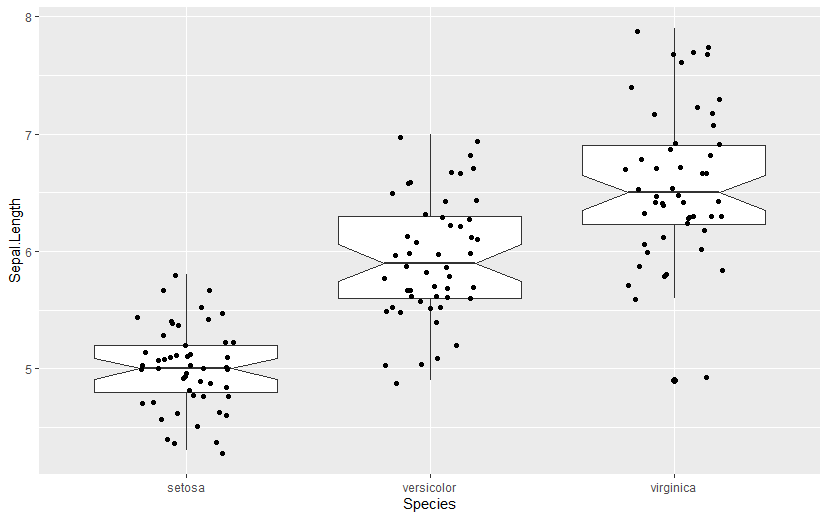

The two key functions for aggregating using dplyr are group_by() and summarize(). Let us dive into an example right away. Let us use the classic built-in iris dataset:

Code

data("iris")

iris$Species %>% unique()Output

[1] setosa versicolor virginica

Levels: setosa versicolor virginicaSo we have the following unique Species:

setosaversicolorvirginica

We can group by Species and get some summary statistics for each group:

Code

# Group by Species & calculate summary stats

iris_summarized <- iris %>%

group_by(Species) %>%

summarize(Mean.Petal.Length = mean(Petal.Length),

Mean.Petal.Width = mean(Petal.Width))

# Check head

head(iris_summarized)The result is a tibble object of the specified dimensions:

- Three columns (one for the group name and one for each aggregate).

- Three rows (one per Species).

Output

Species Mean.Petal.Length Mean.Petal.Width

<fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 setosa 1.46 0.246

2 versicolor 4.26 1.33

3 virginica 5.55 2.03The mean() function is just one option, but we can use whichever aggregate function we need, including, of course, custom functions.

8. Data tidying & tidyr

As mentioned previously, tidyr is also included in the tidyverse package. Its main use case is to create tidy data. According to the official documentation, tidy data is data where:

- Every column is a variable.

- Every row is an observation.

- Every cell is a single value.

The importance of using tidy data is that most of the time when using some of the tidyverse packages, functions will work with this format by default and will require additional maneuvers when we present other forms. For example, let us come back to the following dataset:

Code

colnames(df_csv_dataframe)Output

"Country.Name",

"Country.Code",

"Indicator.Name",

"Indicator.Code",

"X1960",

"X1961",

"X1962",

...As we can see, we have the following columns:

Country.Name: Identifies the observational unit (country), which is appropriate.Country.Code: Identifies the observational unit (country), which is appropriate.Indicator.Name: Identifies another aspect of the observation, which is also appropriate.Indicator.Code: Identifies another aspect of the observation, which is also appropriate.X1960,X1961,X1962, …,X196n: Represent values of a variable over time (years), which is not appropriate.

The problem is that “year” is supposed to be a variable; instead, we’re saying that each year is a variable in and of itself. In its current form, our dataframe does not adhere to the principles of a “tidy” dataframe as defined by the tidyverse philosophy.

This dataset format is fine when we’re performing simple calculations using dplyr or even Base R; however, the problem is more evident when visualizing our data:

ggplot2is designed with the assumption that data is tidy. This design makes it straightforward to map variables to aesthetic attributes like x and y axes, color, size, etc.- Tidy data allows for more flexible and complex visualizations. We can easily switch between different types of plots or layer multiple types of visualizations together without significantly restructuring our data.

- Tidy data simplifies the process of creating facets (subplots based on data subsets) or grouping data.

If our data is not tidy:

- We’ll generally still be able to plot, but there might be limited features, specially for more advanced plotting.

- We’ll most probably be doing extensive data transformations inside the plotting code, which is far from ideal.

Going back to the previous example, imagine plotting a time series for this metric; we would have to maneuver over the fact that the time variable is scattered across all columns instead of indicating a single column.

So in short, using tidy data in tidyverse is always recommended; we’ll always use tidy data in this series when creating visual objects, and also sometimes when performing transformations.

8.1 Generating tidy data

tidyr has a ton of functions; we’ll not be using all of them, of course. In this series, we’ll mostly be using the following:

pivot_longer: Transform from wide to long.pivot_wider: Transform from long to wide.

Let us start with a simple example, where we would like to tidy our df_csv_dataframe. In short, we need to:

- Take all columns containing yearly entries.

- Convert them to a single column called

year. - For each observation, expand vertically to accommodate all years in a single column.

And the best of all is that we can use tidyr functions as dplyr transformation steps, making this a breeze to work with:

Code

# Tidy data (use year cols)

df_csv_dataframe_longer <- df_csv_dataframe %>%

pivot_longer(cols = starts_with('X'),

names_to = "year")

# Check head

head(df_csv_dataframe_longer)Let us break this down in more detail:

- The data structure will always be the first argument for

pivot_longer. However, we’re piping usingdplyrsyntax, so this is not required (we’re piping the actual object). - The second argument is the column set we would like to transform to a single variable, in this case, all columns starting with the character ‘X’.

- The third argument is the column’s name that will store our converted observations (previously single variables). By default, R will set this as

name. - The fourth argument indicates the column’s name that will contain the values. By default, R will set this as

value.

Output

Country.Name Country.Code Indicator.Name Indicator.Code Year Value

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD X1960 NA

2 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD X1961 NA

3 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD X1962 NA

4 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD X1963 NA

5 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD X1964 NA

6 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD X1965 NAWell this is nice, but how do we get rid of the X prefix? (This happens because when loading datasets, R sometimes prepends numeric columns with a string character X.) We don’t want this in our dataset, right? Turns out tidyr devs thought of this already, and implemented a nice names_prefix argument we can use to get rid of any prefix in our names column:

Code

# Tidy data (use year cols)

df_csv_dataframe_longer <- df_csv_dataframe %>%

pivot_longer(cols = starts_with('X'),

names_to = "Year",

values_to = "Value",

names_prefix = 'X')

# Check head

head(df_csv_dataframe_longer)Output

Country.Name Country.Code Indicator.Name Indicator.Code Year Value

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1960 NA

2 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1961 NA

3 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1962 NA

4 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1963 NA

5 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1964 NA

6 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1965 NAFair, but what if we don’t have the X prefix to work with in the first place? Since we’re counting on it in order to know which columns to convert to observations, we’ll have to perform some previous steps first:

Code

# Create a new df_csv_dataframe from our data.table object

# data.tables do not automatically prepend numeric col names with X

df_csv_dataframe <- as.data.frame(df_csv_datatable)

# Declare base cols (we'll respect these)

base_cols <- c("Country Name",

"Country Code",

"Indicator Name",

"Indicator Code")

# User pivot_longer without column prefixes

df_csv_dataframe_longer <- df_csv_dataframe %>%

pivot_longer(cols = !all_of(base_cols),

names_to = "Year",

values_to = "Values")

# Check head

head(df_csv_dataframe_longer)Output

`Country Name` `Country Code` `Indicator Name` `Indicator Code` Year Values

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1960 NA

2 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1961 NA

3 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1962 NA

4 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1963 NA

5 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1964 NA

6 Aruba ABW GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD 1965 NALet us break this down in more detail:

- We first make a copy of our

data.tableobject so that we get the year names without the prependedXcharacter. - We then define a new vector called

base_cols.This object will contain the columns we want to keep intact when executing the transformation. - Lastly, we call

pivot_longer, but instead of indicating a set of columns to pivot, we declare all columns except the base columns. - The rest stays exactly the same.

8.2 Generating untidy data

Of course, we can do the inverse operation as we did in the last example and make our data object wider by pivoting column values as new variables. This comes in handy when we get a dataset that has the following columns:

- Variable: A set of variables.

- Value: A set of values corresponding to each of the variables.

When in reality, we should have:

- One variable per column.

- One observation per row.

Let us try to do an example:

Code

# Declare Dataframe

# Declare variables column

df_variables <- c("Height",

"Width",

"X Coordinate",

"Y Coordinate")

# Declare values column

df_values <- c(10,

20,

102.3,

102.4)

# Declare frame using vectors as columns

df_long <- data.frame(variables = df_variables,

values = df_values)

# Check head

head(df_long)Output

variables values

1 Height 10.0

2 Width 20.0

3 X Coordinate 102.3

4 y Coordinate 102.4So, what we need to do is convert every variable to a new column and set each value in a row. Each row would be a new observation, but this dataframe only has one observation (let us call it object A). Hence, our object will only contain 1 row:

Code

# Pivot wider in order to get tidy object

df_wider <- df_long %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = variables,

values_from = values)

# Check head

head(df_wider)Output

Height Width `X Coordinate` `y Coordinate`

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 10 20 102. 102.And that’s it; we’ve transformed our original dataset into a tidy set by using tidyr & dplyr.

9. Merging objects

Merging is a crucial part of data manipulation, and we’ll be doing a lot in this series. Merging works very similarly to other languages, such as Python. There are different types of merge operations, depending on the underlying set theory implementation we’d like to use.

Merging in R can be executed using multiple libraries. However, we’ll use three in this series:

- Base R

dplyrtidyverse

9.1 Merging using Base R

Base R provides us with a merge() function. We can use it to perform the following join operations:

- outer

- left

- right

- inner

However, the function is the same, and what changes in this case is the join argument we pass:

Code

# Using Base R merge()

# Define two frames

df_countries <- data.frame(country_key = c("SEN", "LTU", "ISL", "GBR"),

country = c("Senegal", "Lituania", "Iceland", "United Kingdom"))

df_metrics_1 <- data.frame(country_key = c("LTU", "MEX", "GBR", "SEN", "ISL"),

metric = c(23421, 234124, 25345, 124390, 34634))

df_metrics_2 <- df_metrics <- data.frame(country_key = c("LTU", "SEN", "CHE", "GBR", "ISL"),

metric = c(37824, 89245, 28975, 49584, 29384))

# Create new frame merging left for df_countries on key

df_left_base <- merge(df_countries, df_metrics_1, by = "country_key", all.x = TRUE)

# Check head

head(df_left_base)

# Create new frame merging right for df_metrics on key

df_right_base <- merge(df_countries, df_metrics_1, by = "country_key", all.y = TRUE)

# Check head

head(df_right_base)

# Create new frame merging inner on key

df_inner_base <- merge(df_countries, df_metrics_1, by = "country_key", all = FALSE)

# Check head

head(df_inner_base)

# Create a new frame by merging df_left_base with df_metrics_2 using left_merge

df_left_base <- merge(df_left_base, df_metrics_2, by = "country_key", all.x = TRUE)

# Check head

head(df_left_base)Output

country_key country metric

1 GBR United Kingdom 25345

2 ISL Iceland 34634

3 LTU Lituania 23421

4 SEN Senegal 124390

country_key country metric

1 GBR United Kingdom 25345

2 ISL Iceland 34634

3 LTU Lituania 23421

4 SEN Senegal 124390

country_key country metric.x metric.y

1 GBR United Kingdom 25345 49584

2 ISL Iceland 34634 29384

3 LTU Lituania 23421 37824

4 SEN Senegal 124390 892459.2 Merging using dplyr

We already saw that dplyr has very nice transformation functions. Additionally, it also provides merge functions. However, these vary with regards to the join operation we’re trying to perform:

Code

# Using dplyr

df_left_dplyr <- df_countries %>%

left_join(df_metrics_1, by = "country_key") %>%

inner_join(df_metrics_2, by = "country_key")

# Check head

head(df_left_dplyr)Output

country_key country metric.x metric.y

1 SEN Senegal 124390 89245

2 LTU Lituania 23421 37824

3 ISL Iceland 34634 29384

4 GBR United Kingdom 25345 495849.3 Merging using purr

At last, we have the reduce() function from the purr package. The reduce() function is not just a merge function; it’s much more than that. The reduce() function is a commonly used method in functional programming. In fact, it’s one of the staples of any FP language along with map() and mapreduce().

The reduce() function will reduce a list of objects to a single object by iteratively applying a function. We have two flavors:

reduce(): Will reduce from left to right (we’ll be mostly using this one)reduce_right(): Will reduce from right to left.

Let us put reduce() in practice by using our previous examples:

Code

# Using purr's reduce() function

df_list <- list(df_countries,

df_metrics_1,

df_metrics_2)

df_left_reduce <- df_list %>%

reduce(left_join, by = "country_key")

# Check head

head(df_left_reduce)Output

country_key country metric.x metric.y

1 SEN Senegal 124390 89245

2 LTU Lituania 23421 37824

3 ISL Iceland 34634 29384

4 GBR United Kingdom 25345 49584This approach has three main advantages that we’ll greatly leverage throughout this series:

- We can merge n number of objects using one single expression.

- It fits seamlessly with

dplyr. - We can use any function, including custom functions (of course, not just necessarily for merging).

10. Classical statistics

This mini tutorial would not be complete without going over some of the very basic classical statistics concepts in R, given that R is a statistics-oriented programming language, and we’ll be making fairly extensive use of some of the methods included. Please keep in mind that this is in no way a comprehensive review of classical statistics theory. Instead, it’s a very quick mention of the most relevant methods in R and how we’ll implement them in our analyses.

10.1 Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics are a key aspect of Data Science & Data Analysis. They provide ways of summarizing & describing data and are used extensively in Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) since they often provide a friendly & comprehensive entry point where our data is extensive.

In the words of Jennifer L. Green et al., descriptive statistics summarize the characteristics and distribution of values in one or more datasets. Classical descriptive statistics allow us to have a quick glance at the central tendency and the degree of dispersion of values in datasets. They are useful in understanding a data distribution and in comparing data distributions.

Descriptive statistics can be categorized based on what they measure:

- Measures of Frequency

- Examples: Count, Percent, Frequency.

- Objective: Shows how often something occurs.

- Measures of Central Tendency

- Examples: Mean, Median, and Mode.

- Objective: Locates the distribution by various points.

- Measures of Dispersion or Variation

- Examples: Range, Variance, Standard Deviation.

- Objective: Identifies the spread of scores by stating intervals.

- Measures of Position

- Examples: Percentile Ranks, Quartile Ranks.

- Objective: Describes how scores fall in relation to one another. Relies on standardized scores.

R has implementations for all of the statistics above. They’re simple to use and can also be obtained using summarization functions:

Code