Exploratory data analysis (EDA) is a scientific technique developed by the mathematician John Tukey in the 1970s widely used in Data Science. It consists of performing initial investigations on a data set so as to have a better understanding of its nature, and potentially use it for business or academic applications. This technique provides valuable insight in a quick way, and is useful when we are working with large data sets.

There is no rule of thumb regarding the steps to take in order to perform an EDA, because data varies between cases. Additionally, the purpose of why we’re using this technique in the first place also varies.

In a general way, an EDA could consist of the following:

- Understand the structure of the data.

- Evaluate if preprocessing is required. If so, generate a methodology for preprocessing.

- Uncover general patterns not visible at simple sight.

- Using statistical descriptions.

- Using visualization techniques.

For more specific applications, we could include more advanced methods such as studying variable correlations using statistical methods, or even testing ML methods such as linear regression or classification techniques to evaluate if the information could be useful to us.

In this 3-article Guided Project, we will discuss some popular EDA approaches, specific libraries to perform diagnostics & statistical analysis, visualization techniques for better understanding our data, and more advanced ML techniques.

We’ll be using Python scripts which can be found in the Guided Project Repo.

Exploratory Data Analysis methods

EDA can be divided into four types, depending on the nature of our data set and the tools we use to analyze it:

1. Univariate, non-graphic

This analysis contemplates the study of a single variable using non-graphical methods. It’s the simplest one of the four. We can have an extensive data set with multiple potential study variables. Still, if we leave them all out and focus on one, it will be a univariate analysis. This is tricky because stating the variables we will study could be part of our EDA. The decision of which method to use should be a product of the problem statement, i.e. what we’re trying to achieve with our analysis.

2. Bivariate, graphic

This analysis contemplates the study of two variables and their potential correlation. It includes visualization methods helpful in studying multiple variable correlations. Some of the visualization methods most commonly used include:

- Histograms for studying the overall distribution of each variable.

- Box plots for studying the data distribution of each variable, along with some important statistics such as mean and quartiles.

- Scatterplots for studying the correlation between two variables.

3. Multivariate, non-graphic

This analysis contemplates the same study as above but includes visualization methods. We can use multiple plots, but the most commonly used are:

- Bar charts with an x-axis including multiple independent variables and a y-axis including one dependent variable.

- Pair plots including scatter plots and histograms.

Why perform an EDA?

EDA has become a big thing in Data Science. It’s sometimes referred to as a vital step in understanding data, and it’s true. Still, we need to remember that not because everyone’s using it, we should also be using it, at least as the step-by-step approach we mentioned earlier.

It’s very easy to get our hands on some data and start performing tests which could be useless for our case. Before attempting to write any code, it’s vital first to understand what we are trying to achieve, where this data set came from, how it was generated and what is expected out of the analysis, and only then design a methodology that will help us solve our business problem. True, we don’t always know all these variables, and an EDA could answer some of them, but we should at least try to have clarity on what we’re trying to do.

In cases like this, it’s helpful to state a business case and then design a scientific methodology that will help us solve that problem logically.

A simple business case

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide, accounting for 2.1 million new cases and 1.8 million deaths in 2018. In 1987, it surpassed breast cancer to become the leading cause of cancer deaths in women. An estimated 154,050 Americans are expected to die from lung cancer in 2018, accounting for approximately 25 per cent of all cancer deaths. The number of deaths caused by lung cancer peaked at 159,292 in 2005 and has since decreased by 6.5% to 148,945 in 2016. [1]

Smoking, a main cause of small and non-small cell lung cancer, contributes to 80% and 90% of lung cancer deaths in women and men, respectively. Men who smoke are 23 times more likely to develop lung cancer. Women are 13 times more likely than compared to non-smokers. [1-1]

Lung cancer can also be caused by occupational exposures, including asbestos, uranium and coke (an important fuel in the manufacture of iron in smelters, blast furnaces and foundries). The combination of asbestos exposure and smoking greatly increases the risk of developing lung cancer.[1-2]

Our client, an insurance company, has asked us to conduct a correlational study between different behavioural & genetic characteristics and lung cancer incidence. For this, they provided a medical dataset containing a set of anonymous patients and their medical files generated upon hospital admission.

1. Data set usability

For this example, we will use the Lung Cancer Prediction Dataset by The Devastator which can be found on Kaggle.

One crucial step before selecting a data set is to verify its usability. Typically, this would be part of the actual EDA process, but Kaggle already gives us helpful information. We can head to the Usability section, where we will find a usability score and a detailed breakdown.

For our case, we have the following parameters as of February 2023:

- Completeness · 100%

- Subtitle

- Tag

- Description

- Cover Image

- Credibility · 100%

- Source/Provenance

- Public Notebook

- Update Frequency

- Compatibility · 100%

- License

- File Format

- File Description

- Column Description

This tells us that according to Kaggle, our data set is entirely usable, complete, fully credible & fully compatible.

Evaluating usability is important because we might have an initial idea which is not feasible due to the nature of the data set. In real life, we may not have the privilege of choosing between data sets and selecting the most complete or credible. Still, we can talk to the people responsible for the data generation to understand better what we’re dealing with. This is a common practice in the industry, especially when the data is generated in-house and does not come from an external source; we can talk with the data engineers responsible for data sourcing and get a complete description of the data structure and maybe even some usability parameters. In some cases, we can even request a data reformatting previous to data import if this is something we would deploy in a production environment and notice inconsistencies with how the data is being handled. Again, every situation is different, and there is no rule of thumb for how to deal with data sets during the preprocessing steps.

Kaggle also offers a section including the data set head and a simple histogram for each column. Since this feature would most likely not be in our hands when working with real-world data, we will skip it and figure it out ourselves.

Now that we know more about the usability of our data set, we can download it.

2. Understanding our data set

We will first import the required modules. These will be used throughout the entire Guided Project:

Code

# Data manipulation modules

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import xlsxwriter

# System utility modules

import os

import shutil

from pathlib import Path

# Plotting modules

import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Statistical modules

from scipy.stats import pearsonrWe will also define our plot parameters beforehand:

Code

# Before anything else, delete the Matplotlib

# font cache directory if it exists, to ensure

# custom font propper loading

try:

shutil.rmtree(matplotlib.get_cachedir())

except FileNotFoundError:

pass

# Define main color as hex

color_main = '#1a1a1a'

# Define title & label padding

text_padding = 18

# Define font sizes

title_font_size = 17

label_font_size = 14

# Define rc params

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = [14.0, 7.0]

plt.rcParams['figure.dpi'] = 300

plt.rcParams['grid.color'] = 'k'

plt.rcParams['grid.linestyle'] = ':'

plt.rcParams['grid.linewidth'] = 0.5

plt.rcParams['font.family'] = 'sans-serif'

plt.rcParams['font.sans-serif'] = ['Lora']We will then load our .csv file as a Pandas DataFrame object:

Code

df = pd.read_csv('cancer patient data sets.csv')The first thing we can do is grasp a general understanding of the data set shape and its data types:

Code

print(df.shape)

print(df.dtypes)Output

(1000, 26)

index int64

Patient Id object

Age int64

Gender int64

Air Pollution int64

Alcohol use int64

Dust Allergy int64

OccuPational Hazards int64

Genetic Risk int64

chronic Lung Disease int64

Balanced Diet int64

Obesity int64

Smoking int64

Passive Smoker int64

Chest Pain int64

Coughing of Blood int64

Fatigue int64

Weight Loss int64

Shortness of Breath int64

Wheezing int64

Swallowing Difficulty int64

Clubbing of Finger Nails int64

Frequent Cold int64

Dry Cough int64

Snoring int64

Level object

dtype: objectWe can see that our Data Frame contains 1,000 rows and 26 columns. We can also see that 24 columns have int64 as their data type, and two have object, in this case, meaning string types.

We can then proceed to print the head of our object to see what our data looks like:

Code

print(df.head())Output

index Patient Id Age Gender ... Frequent Cold Dry Cough Snoring Level

0 0 P1 33 1 ... 2 3 4 Low

1 1 P10 17 1 ... 1 7 2 Medium

2 2 P100 35 1 ... 6 7 2 High

3 3 P1000 37 1 ... 6 7 5 High

4 4 P101 46 1 ... 4 2 3 High

[5 rows x 26 columns]Upon taking a closer look at the output, we can confirm that the two object type variables are, in fact, strings. The other variables appear to be categorical, except for age, which is numerical.

A categorical variable is a variable that can take on one of a limited and usually fixed range of possible values. A categorical variable is limited by the data set itself, and its meaning and magnitude are assigned by the data set author.

Categorical variables can be classified as nominal or ordinal.

A categorical nominal variable describes a name, label or category without natural order. An example could be a binary representation of sex, i.e. male = 0, female = 1.

A categorical, ordinal variable is one whose values are defined by an order relation between the different categories. An example could be the level of exposure to a given chemical, i.e. low exposure = 1, medium exposure = 2, high exposure = 3.

As we will see soon, having categorical variables as integers instead of strings is helpful since many ML methods accept categorical variables as arrays of integers. The act of converting non-numerical variables to numerical values is called dummifying, though we will not cover it here in detail.

This information will also be beneficial once we start designing our features for an ML model implementation, a process also called feature engineering.

Before moving to the next step, we can check for null values in any of our columns:

Code

print(df.isnull().values.any())Output

FalseThe output tells us that our data set does not contain any null value. This was also specified in the Completeness parameter inside the Usability section.

We can also remove the index column:

Code

df.drop(columns = "index", inplace = True)Finally, we can also confirm that we have a unique set of patient ID’s, so as not to include duplicates in our analysis:

Code

print(df['Patient Id'].nunique())Output

10003. Initial investigations

In order to make more sense of the data set, we can perform some simple statistical descriptions of each variable. This will help us understand how we can start using our data, its limitations and, eventually, start designing potential prediction methodologies.

We can begin by performing a statistical description of our variables:

Code

round(df.describe().iloc[1:, ].T, 2)Output

mean std min 25% 50% 75% max

Age 37.17 12.01 14.0 27.75 36.0 45.0 73.0

Gender 1.40 0.49 1.0 1.00 1.0 2.0 2.0

Air Pollution 3.84 2.03 1.0 2.00 3.0 6.0 8.0

Alcohol use 4.56 2.62 1.0 2.00 5.0 7.0 8.0

Dust Allergy 5.16 1.98 1.0 4.00 6.0 7.0 8.0

OccuPational Hazards 4.84 2.11 1.0 3.00 5.0 7.0 8.0

Genetic Risk 4.58 2.13 1.0 2.00 5.0 7.0 7.0

chronic Lung Disease 4.38 1.85 1.0 3.00 4.0 6.0 7.0

Balanced Diet 4.49 2.14 1.0 2.00 4.0 7.0 7.0

Obesity 4.46 2.12 1.0 3.00 4.0 7.0 7.0

Smoking 3.95 2.50 1.0 2.00 3.0 7.0 8.0

Passive Smoker 4.20 2.31 1.0 2.00 4.0 7.0 8.0

Chest Pain 4.44 2.28 1.0 2.00 4.0 7.0 9.0

Coughing of Blood 4.86 2.43 1.0 3.00 4.0 7.0 9.0

Fatigue 3.86 2.24 1.0 2.00 3.0 5.0 9.0

Weight Loss 3.86 2.21 1.0 2.00 3.0 6.0 8.0

Shortness of Breath 4.24 2.29 1.0 2.00 4.0 6.0 9.0

Wheezing 3.78 2.04 1.0 2.00 4.0 5.0 8.0

Swallowing Difficulty 3.75 2.27 1.0 2.00 4.0 5.0 8.0

Clubbing of Finger Nails 3.92 2.39 1.0 2.00 4.0 5.0 9.0

Frequent Cold 3.54 1.83 1.0 2.00 3.0 5.0 7.0

Dry Cough 3.85 2.04 1.0 2.00 4.0 6.0 7.0

Snoring 2.93 1.47 1.0 2.00 3.0 4.0 7.0Some of these variables can be verified by common sense. We know, for example, that Age values should belong to a close interval. We also know we should have two unique values for the Gender variable.

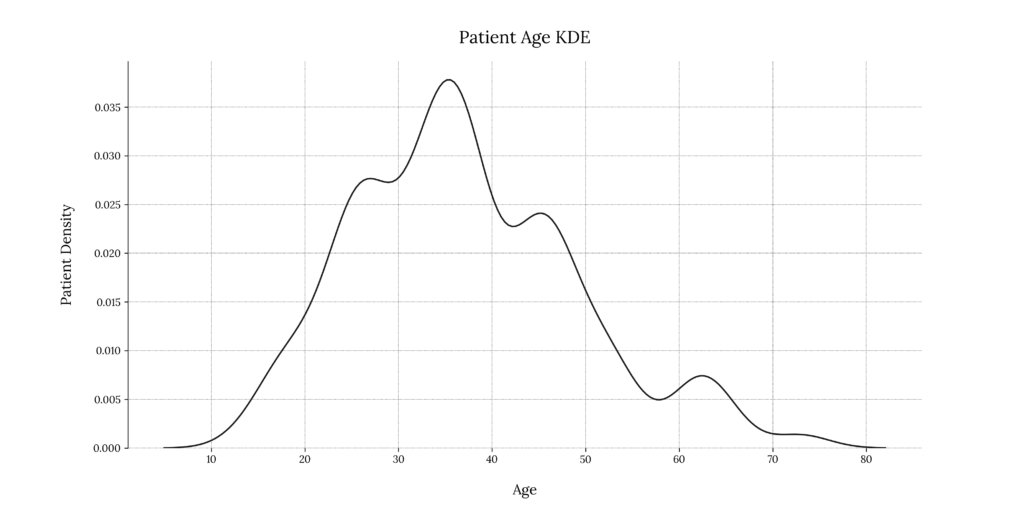

We can get to know our sample better by plotting a Kernel Density Estimate (KDE) plot to visualize the Age distribution. This method will return a plot for a smoothed probability density function:

Code

# Create figure

plt.figure('Patient Age Distribution')

# Plot the age distribution

sns.kdeplot(df['Age'], color = color_main)

# Enable grid

plt.grid(True, zorder=0)

# Set xlabel and ylabel

plt.xlabel("Age", fontsize=label_font_size, labelpad=text_padding)

plt.ylabel("Patient Density", fontsize=label_font_size, labelpad=text_padding)

# Remove bottom and top separators

sns.despine(bottom=True)

# Add plot title

plt.title('Patient Age KDE', fontsize=title_font_size, pad=text_padding)

# Optional: Save the figure as a png image

plt.savefig('plots/' + '01_patient_age_KDE.png', format = 'png', dpi = 300, transparent = True)

# Close the figure

plt.close()Output

We can see that our population distribution is skewed towards the center-left. The range of age with the highest number of incidences lies between 22 and 26 years of age. We can also notice an increased number of cases in the range of 38 to 40 years.

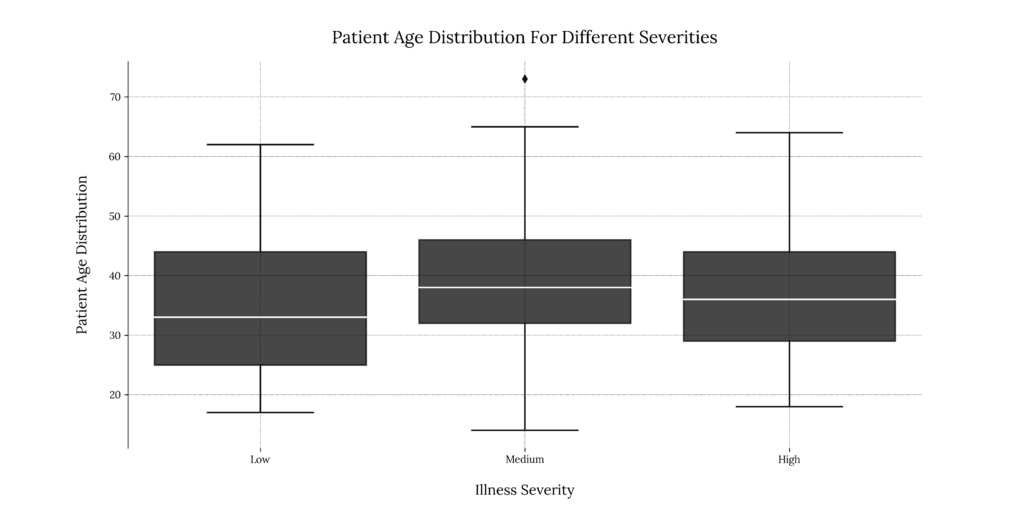

Now that we have an idea of the overall age distribution for our sample, we can try to understand the age distribution for each level of Cancer affectation. For this, we have the Level variable available, denoting illness severity.

The way we can do this is by using a boxplot:

Code

# Create figure

plt.figure('Patient Age Distribution For Different Severities')

# Plot the age distribution for different illness severities

sns.boxplot(x='Level',

y='Age',

data=df,

order=["Low", "Medium", "High"],

color=color_main,

medianprops=dict(color="white", label='median'),

boxprops=dict(alpha=0.8))

# Enable grid

plt.grid(True, zorder=0)

# Set xlabel and ylabel

plt.xlabel("Illness Severity", fontsize=label_font_size, labelpad=text_padding)

plt.ylabel("Patient Age Distribution", fontsize=label_font_size, labelpad=text_padding)

# Remove bottom and top separators

sns.despine(bottom=True)

# Add plot title

plt.title('Patient Age Distribution For Different Severities', fontsize=title_font_size, pad=text_padding)

# Remove subplot title

plt.suptitle('')

# Optional: Save the figure as a png image

plt.savefig('plots/' + '02_patient_age_distribution_for_different_severities.png', format = 'png', dpi = 300, transparent = True)

# Close the figure

plt.close()Output

This gives us little information; for low severity, patients range primarily from 25 to 43 years, the median being roughly 33 years of age. For medium & high severity, the median age appears to be slightly higher, approximately 38 and 36 years, consecutively. We also seem to have one outlier in the Medium severity group.

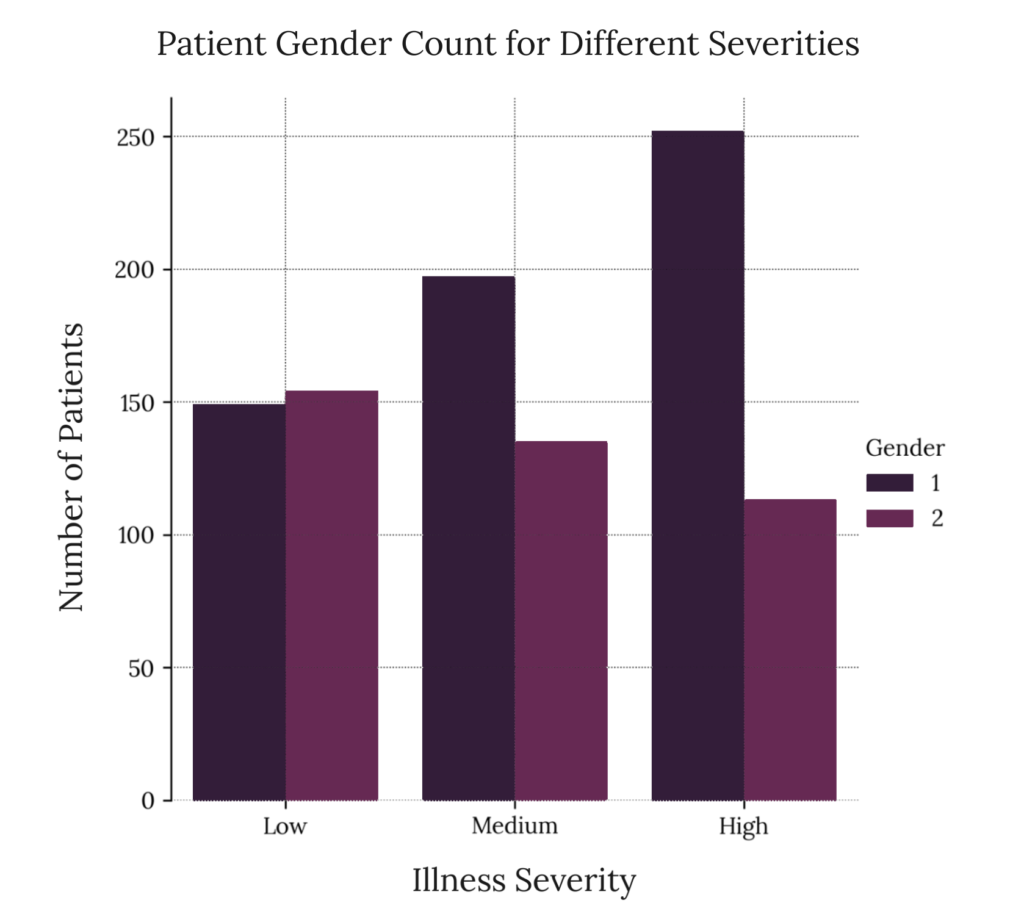

We can further investigate if the Gender variable plays a role in the illness severity for our sample. We can do so by using a grouped bar chart:

Code

# Create figure

plt.figure('Patient Gender Composition For Different Severities')

# Plot the age distribution for different illness severities

df_group = df.groupby(['Level', 'Gender'])['Patient Id'].count().reset_index()

sns.catplot(data=df_group,

kind="bar",

x="Level",

y="Patient Id",

hue="Gender",

palette = sns.color_palette("rocket"),

alpha=0.8,

order=["Low", "Medium", "High"]

)

# Enable grid

plt.grid(True, zorder=0)

# Set xlabel and ylabel

plt.xlabel("Illness Severity", fontsize=label_font_size, labelpad=text_padding)

plt.ylabel("Number of Patients", fontsize=label_font_size, labelpad=text_padding)

# Remove bottom and top separators

sns.despine(bottom=True)

# Add plot title

plt.title('Number of Patients For Different Severities', fontsize=title_font_size, pad=text_padding)

# Remove subplot title

plt.suptitle('')

# Optional: Save the figure as a png image

plt.savefig('plots/' + '03_patient_gender_count_for_different_severities.png', format = 'png', dpi = 300, transparent = True)

# Close the figure

plt.close()Output

This tells us more about the potential nature of illness affectation in our sample; medium and high affectation levels are more prevalent in men, while low affectation levels are roughly equal. This is by no means a quantitative analysis and does not provide a potential correlation. We must employ more rigorous statistical methods to start generating a valid hypothesis.

4. Variable correlation study

There are multiple statistical methods and visualization techniques that can come in handy. For studying a potential bivariate correlation, we typically use correlation matrices for tabular-like visualizations or scatterplots for graphical visualizations. The first provides a quantitative result, while the latter provides a qualitative result.

Since we have a large number of variables and we don’t know which ones we could use to predict illness severity, we will start by using a variation of the correlation matrix by employing a correlation heat map.

4.1 Using a correlation matrix

A correlation matrix is a standard statistical technique which generates pairs for all variables and calculates a correlation coefficient, including all variables paired with themselves denoted in the matrix diagonal.

Pandas has a built-in method, df.corr(), which accepts a Data Frame and returns a correlation matrix populated with correlation coefficients for each pair of variables. The advantage of this method is that we can decide between three different correlation methods, the default being the Pearson correlation coefficient. This will be important because of the nature of our data.

For our example, the Pearson coefficient is not helpful since we have categorical, ordinal data (The Pearson correlation method is adequate for continuous, linear variables). A better approach for our case would be to employ a rank correlation coefficient such as Spearman’s or Kendall’s; both are included in the df.corr() method.

If we are to use the Spearman correlation, we must consider some assumptions:

- Our data must be at least ordinal.

- The scores on one variable must be monotonically related to the other variable.

The first assumption is covered. The second assumption is more problematic since we have yet to determine if all of our variable pairs are monotonic, i.e. as one variable increases, the other one increases (monotonically increasing), or as one variable decreases, the other one decreases (monotonically decreasing).

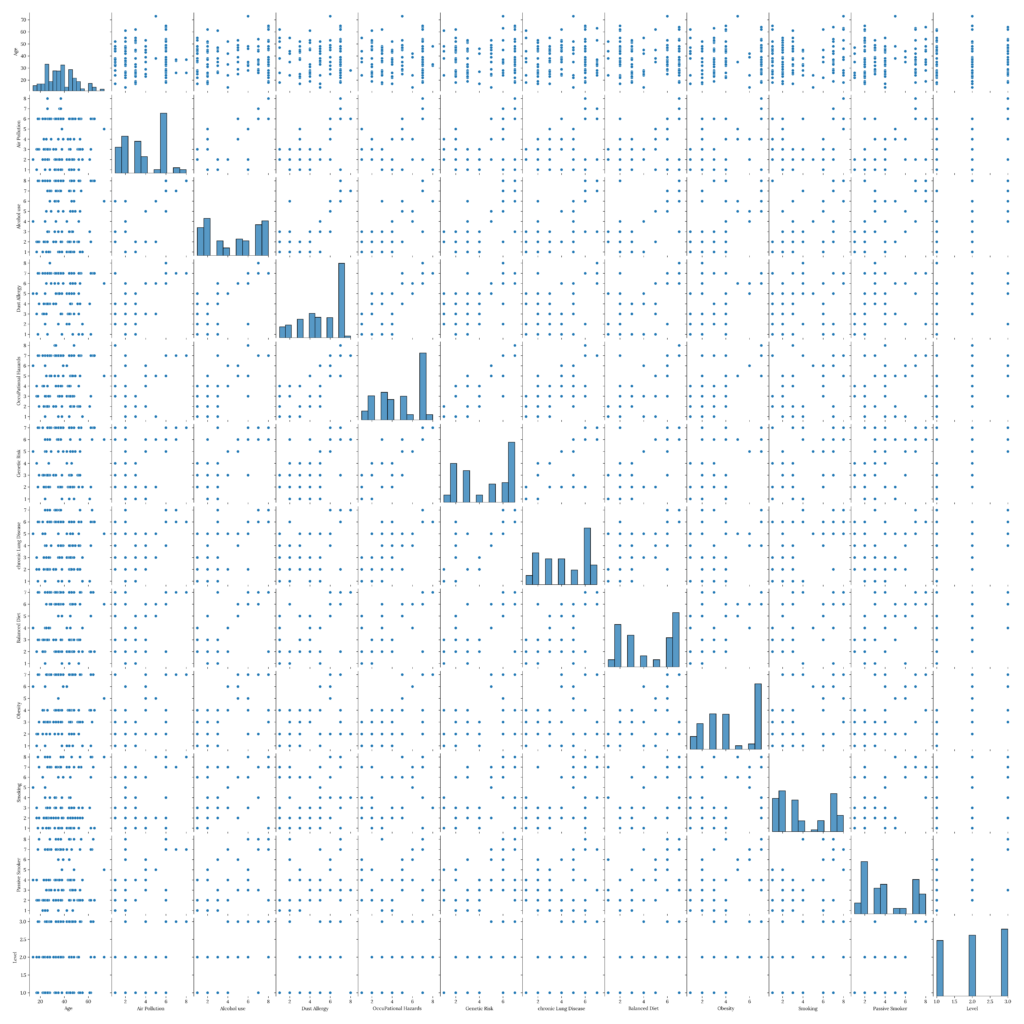

We can perform a simple test by using a pair plot. This visualization technique plots pairwise relationships in a dataset in the form of scatterplots, including all variables with themselves denoted in the diagonal of the output matrix as histograms. It’s very similar to our heat map approach, only that we’re plotting the variables, so first, we will need to select the ones we will include.

Referring back to our business case:

- We’re looking for risk factors that could result in higher Lung Cancer severity levels, such as smoking habits and air pollution exposure levels.

- We’re not looking for symptomatic variables describing the patient’s actual health status, such as sneezing, coughing or snoring. This would be irrelevant to our client.

- We will also not include the

Gendervariable since it does not comply with our ordinal assumption.

In the end, we’re left with the following:

Patient Id(As an identifier, though we will not include it in the correlation analysis)AgeAir PollutionAlcohol useDust AllergyOccuPational HazardsGenetic Riskchronic Lung DiseaseBalanced DietObesitySmokingPassive SmokerLevel

We will also need to convert our Levels variable to a categorical, ordinal numerical format:

Code

# Define variables to keep

ordinal_vars = ['Patient Id',

'Age',

'Air Pollution',

'Alcohol use',

'Dust Allergy',

'OccuPational Hazards',

'Genetic Risk',

'chronic Lung Disease',

'Balanced Diet',

'Obesity',

'Smoking',

'Passive Smoker',

'Level']

# Create new Data Frame

df_corr = df[ordinal_vars]

# Map Level to numeric values

illness_level_dict = {'Low' : 1,

'Medium' : 2,

'High': 3}

df_corr['Level'] = df_corr['Level'].map(illness_level_dict)

# Remove Patient Id variable for correlation study

df_corr_m = df_corr.drop(columns = ['Patient Id'])

# Plot a pair plot

# Create figure

plt.figure('Pair Plot', figsize=(20, 22))

# Plot Pair Plot

g = sns.pairplot(df_corr_m)

# Enable grid

plt.grid(True, zorder=0)

# Remove bottom and top separators

sns.despine(bottom=True)

# Add plot title

g.fig.suptitle('Pairplot for All Categorical Variables', y=1.02, fontsize=title_font_size)

# Optional: Save the figure as a png image

plt.savefig('plots/' + '04_pairplot_categorical_variables.png', format = 'png', dpi = 300, transparent = True)

# Close the figure

plt.close()Output

It’s challenging to see the actual data points data because of our number of variables. We could analyze our variables pair by pair and investigate each case, but this would take more time and, in our case, is unnecessary. Also, our data set is small, and we’re working with discrete categorical data, so our scatterplots will display separated data points in many cases. Nevertheless, if we pay close attention, we will notice that, in most cases, variable combinations present increasing monotonicity.

Now that we have a general notion of our variable pair trends, we can conduct a Spearman correlation analysis:

Code

# Spearman Correlation Analysis

# Create figure

plt.figure('Spearman Correlation Heatmap for Risk Factor Variables', figsize=(20,18))

# Create the correlation matrix

df_corr_ms = df_corr_m.corr(method='spearman')

# Plot using heat man

sns.heatmap(round(df_corr_ms, 2), annot=True, cmap=sns.cm.rocket_r)

# Enable grid

plt.grid(True, zorder=0)

# Remove bottom and top separators

sns.despine(bottom=True)

# Add plot title

plt.title('Spearman Correlation Heatmap for Risk Factor Variables', fontsize=title_font_size, pad=text_padding)

# Remove subplot title

plt.suptitle('')

# Optional: Save the figure as a png image

plt.savefig('plots/' + '05_spearman_correlation_heatmap_risk_factor_categorical_variables.png', format = 'png', dpi = 300, transparent = True)

# Close the figure

plt.close()Output

We can see that most of our variables have at least some degree of correlation (Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient goes from -1 to +1).

The variable with the weakest correlation in all cases is Age, while the variable presenting the strongest correlation with the Level variable appears to be Obesity followed by Balanced Diet and, interestingly enough, Passive Smoker along with Alcohol Use and Genetic Risk.

To make more sense of our results, we can consult a table of correlation coefficient values and their interpretation:

Table 1. Correlation Coefficient Values and Their Interpretation

Taken from “Nonparametric Statistics for Non-Statisticians: A Step-by-Step Approach”.

4.2 Calculating p-values

Calculating correlation coefficients is not enough to determine the degree of correlation between two variables. If we were to deliver our analysis as is, the results would lack statistical significance; as we know, there’s a possibility that two variables can be correlated by chance and that, in reality, one or both of the variables were generated randomly. A p-value test will help us analyze that.

Formally, a p-value is a statistical measurement used to validate a hypothesis against observed data. It measures the probability of obtaining the observed results, assuming that the null hypothesis is true. The lower the p-value, the greater the statistical significance of the observed difference.[2]

We can perform a p-value test for the Spearman Correlation analysis using the scipy.stats spearmanr module. We write the df_corr_ms and the df_pvals_ms DataFrame objects to an Excel Workbook as part of our client deliverable. If we wanted to report these results to our client, we could opt for a tabular format.

For this, we can use the ExcelWriter handler method along with the xlsxwriter engine, which can be installed using pip if required:

Code

pip install xlsxwriterCode

# Copy of dataframe to compare against itself

df_corr_c = df_corr_m.copy()

pvalmat = np.zeros((df_corr_m.shape[1], df_corr_c.shape[1]))

for i in range(df_corr_m.shape[1]):

for j in range(df_corr_c.shape[1]):

# Pearson correlation test

corrtest = spearmanr(df_corr_m[df_corr_m.columns[i]], df_corr_c[df_corr_c.columns[j]])

pvalmat[i,j] = corrtest[1]

# Dataframe for p-values

df_pvals_ms = pd.DataFrame(pvalmat, columns=df_corr_m.columns, index=df_corr_c.columns)

# Round results

df_corr_ms = round(df_corr_ms, 4)

df_pvals_ms = round(df_pvals_ms, 6)

# Export to Excel sheet

writer = pd.ExcelWriter('outputs/Risk_Factor_Analysis.xlsx', engine = 'xlsxwriter')

df_corr_ms.to_excel(writer, sheet_name = 'Spearman_Corr_Coef')

df_pvals_ms.to_excel(writer, sheet_name = 'Spearman_Pvals')

writer.close()We can take a look at our correlation test results as well as the associated p-values:

Output

Table 2. Spearman Correlation Coefficients for Chosen Potential Risk Factor Categorical Variables

Output

Table 3. Spearman p-values for Chosen Potential Risk Factor Categorical Variables

If we look closer at our p-values, we can see that for virtually all variables except for Age, the result is negligible (very close to 0). This means there is a 0% chance that a random process generated the results from our sample. In contrast, there’s a 1.2% chance of random events causing the ‘ Age’ with ‘Level’ correlation.

This tells us enough of what we need to know to start designing a predictive model.

In the next part of this 3-segment Guided Project, we will go over nine different classification algorithms and compare their performance.

Conclusions

In this segment, we introduced the concept of EDA. We put it into practice by conducting correlational studies, specifically, the Spearman correlation test and a statistical significance analysis to unveil potential risk factors for patients with three different severity levels of Lung Cancer.

Countless articles and posts suggest different statistical methods without any theoretical background. It’s essential to understand the underlying theory behind the methods we’re using for our analysis. This is easier said than done, but we must be rigorous in our techniques. Otherwise, we could be delivering biased information to our client.

Finally, choosing the proper visualization methods is vital since each object has a purpose; we could also be misleading our client if we chose incorrect visualization techniques.