Scala is a strong, statically typed, high-level, general-purpose programming language that supports both object-oriented programming and functional programming. It was developed by Martin Odersky & a group of computer scientists at EPFL in Switzerland.

In this Blog Article, we’ll discuss some historical background regarding Scala, the main advantages & disadvantages of the language, and provide an introduction to functional programming and its main traits. We’ll then go over installation & configuration using VS Code & the powerful Metals extension, and creating, compiling & running projects using sbt.

We’ll create our first Scala project and use it to discuss Scala’s main features, general syntax, main constructs, and main types. We’ll close this segment with some next steps for those interested in learning more about Scala & functional programming.

We’ll be using Scala 3 scripts which can be found in the Blog Article Repo.

What is Scala?

Scala, which stands for Scalable Language, is a strong, statically typed, high-level, general-purpose programming language that supports both object-oriented programming and functional programming. It was mainly developed with data-intensive applications in mind and is built on top of Java, which means that Scala compiles to Java bytecode and is executed by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM).

Scala was built with three main purposes in mind:

- To be scalable

- To be powerful

- To be safe

Each of these characteristics is carefully taken care of by a wide variety of carefully-crafted features, such as a robust type hierarchy structure, a wide collection of sophisticated higher-order methods, a reinvention of classes & objects combined with type-driven development, and much more.

1. A brief historical overview

Scala’s journey begins in the early 2000s at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland, under the guidance of Martin Odersky. Drawing from his experiences with Java and functional programming languages, Odersky aimed to design a language that married the best aspects of both worlds. The first version of Scala was released publicly in 2004, and since then, it has evolved significantly.

For example, a turning point came in 2021 with the launch of Scala 3, introducing various new features and changes that made the language even more robust and versatile. While Scala has been growing slowly compared to other languages, it has been gaining more popularity since the Scala 3 release.

2. The foundations

Scala is built on top of Java; it uses the entire Java typeset and the JVM for compilation & execution. This means that many of Scala’s concepts will be familiar if we are already familiar with Java or a similar language. Scala’s interoperability with Java is one of its strongest suits. We can use Java libraries and frameworks in Scala and vice versa. The fact that Scala compiles to Java bytecode and runs on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) provides the advantages of portability, efficiency, and access to the mature ecosystem of Java.

However, while Scala has strong ties with Java, it brings its own innovations and constructs. Scala introduces a rich type system, case classes, traits, and an advanced collection library. It also adds many functional programming features, such as first-class functions, immutability by default, and pattern matching.

A unique aspect of Scala is its fusion of object-oriented and functional programming. Every value is an object, and every operation is a method call in Scala, adhering to object-oriented design principles. At the same time, Scala adopts many principles of functional programming, like higher-order functions and strong support for recursion.

In essence, Scala takes the familiar foundation of Java but builds upon it with its own set of innovative features and design philosophy, creating a truly powerful language for modern programming needs.

Why Scala?

Choosing the right programming language is like choosing the right tool for a job. Scala often stands out as a top contender in software development. Why? Well, it boils down to five key attributes:

- Scalability

- Parallelism

- Security

- Adoption

- Functional programming

1. Scala(bility)

Let’s start with the obvious, given the name: Scala is designed with scalability at its core. It has an innate ability to grow seamlessly alongside the demands of our projects. Whether we’re working on a small script to automate a simple task, building out the core system for a startup, or even if we’re deep in developing a sophisticated, distributed application, Scala just works.

And it’s not just about the size of the projects we’re working on. Scala allows us to write code in a style that suits us. Whether we want to write in a more traditional, object-oriented style or if we want to adopt functional programming, Scala enables us to scale our programming paradigm as well. This kind of flexibility is what makes Scala a truly scalable language, not just in terms of project size but also in terms of programming style and team skill levels.

2. Parallelism

In this era where hardware evolution means more cores, not just faster clock speeds, being able to write software that takes advantage of parallel computing capabilities is becoming increasingly important. This is where Scala comes into its own. Its functional nature and a robust collection of libraries make it significantly easier to write parallel and concurrent programs.

Scala’s support for immutability and higher-order functions allows us to write code that is easier to reason about in a parallel execution context. Furthermore, libraries such as Akka enable us to write resilient message-driven applications, providing powerful abstractions for parallel and concurrent code.

3. Security

Scala’s strong static type system and design decisions around immutability make our code safer. The Scala compiler has a remarkable eye for catching errors at compile-time rather than at run-time, dramatically reducing the likelihood of encountering bugs in production. This emphasis on security can save us a considerable amount of debugging time and make our software more robust.

Beyond this, Scala’s expressiveness and type inference allows us to write concise code without sacrificing readability or safety. This means we spend less time on boilerplate code and more time thinking about the logic and security of our applications.

4. Adoption

Scala isn’t just a language that’s good on paper. It’s got credibility among top-tier companies all around the world. Multinational tech companies like Twitter, LinkedIn, and Netflix have all integrated Scala into their tech stacks, and for good reasons.

Below is a list of just some companies that currently use Scala in some part of their process:

- Twitter: They use Scala to handle their immense scale. It is used in their core API services due to its functional nature and powerful concurrency libraries.

- LinkedIn: LinkedIn uses Scala for high-performance applications. The Play Framework, which is written in Scala, is used heavily for building web services.

- Netflix: Netflix uses Scala in their recommendation and personalization algorithms, given Scala’s powerful data processing libraries and capabilities.

- Airbnb: Airbnb uses Scala for data analysis and processing. Its Apache Spark integration, also written in Scala, is particularly valuable for processing large datasets.

- Guardian: The Guardian newspaper uses Scala for their content management system, allowing them to efficiently manage and distribute a vast amount of content.

- SoundCloud: SoundCloud uses Scala for processing its enormous amount of data and to handle its back-end services.

- Sony: Sony uses Scala in their Playstation Network backend services for its robustness and reliability.

- Foursquare: Foursquare uses Scala to handle its location-based services and data.

- Zalando: The European fashion platform uses Scala for many of their backend services and for data processing.

- UBS: The global bank uses Scala for creating high-performance systems in their financial services.

- Apache Spark Project: The Apache Spark project uses Scala for its powerful data processing and distributed computing capabilities.

- Coursera: The online learning platform uses Scala for backend services, providing scalability and efficiency in serving millions of learners.

5. Functional programming

Finally, Scala shines when it comes to functional programming. With its sophisticated blend of functional and OOP paradigms, Scala provides an excellent platform to delve into functional programming. It allows us to take a gentle step into the functional domain, letting us embrace it to the extent we’re comfortable with, without forcing us into a complete paradigm shift overnight.

What to expect

Scala leverages multiple core functionalities, such as a rich type system, implicits, advanced pattern matching, powerful abstraction capabilities, and much more, to execute safely and highly-performantly. However, this makes Scala difficult to learn, even when discussing introductory topics.

Because of this, we must set realistic expectations: Scala takes time to get used to since the way of thinking for writing proper Scala code is different from other languages; it elegantly combines functional & OOP to create powerful abstractions; this means that we might have to think of how to approach problems differently.

1. The Scala way of thinking

We can, of course, write Scala code as if it were Python (with some exceptions, of course), but we would not be leveraging the full power that this language has in store for us. To properly write a Scala application, we must think the Scala way.

This encompasses one main rule of thumb: Scala seamlessly combines two programming paradigms while enforcing the key components of each one, unlike other languages that can be thought of as more “relaxed“:

- Functional: Immutability, higher-order functions, pattern matching for comprehensions, collections, and functional transformations.

- Object-Oriented: Classes and objects, traits, inheritance and polymorphism, and encapsulation.

So, what does this mean? Well, in practical terms, the Scala way of thinking can be summarized in six core concepts:

- Embracing immutability: It’s easy to reassign variables as we write our code, but this significantly affects compile time, execution performance, and safety. Thinking in terms of immutability forces us to be creative when approaching problems: one excellent example is using recursion in favor of loops.

- Using pattern matching and deconstruction: Pattern matching can be considered the more powerful brother of

if-elsestatements: this technique can be used for checking types and deconstructing complex data structures. - Adjusting to a type-driven development: If there’s one fundamental aspect that can take time to get used to when coming from other dynamically-typed languages, it’s type-driven development. It lets us think of our code less ambiguously; we don’t have to guess the expected input & output types in a function because we closely delimit the rules of what can and cannot be done. We can use multiple techniques such as type annotations, type inheritance, bounds, and higher-kinded types for this.

- Favoring composition over inheritance: Although Scala supports inheritance, it encourages using composition and traits to promote code reuse and modularity.

- Using powerful abstractions: Scala enables the creation of powerful abstractions, such as type classes, implicit conversions, and context bounds. While Python has similar features, such as decorators and context managers, Scala’s features are more versatile and expressive.

- Taking advantage of concurrency and parallelism: This one does not apply to all Scala applications but is one characteristic deeply embedded in the Scala ecosystem. It provides excellent support for concurrent and parallel programming through libraries like Akka, Spark, Cats Effect, and Monix. This differs from Python, which has the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) that can limit parallelism.

- Unit testing: Unit testing is relevant in most modern programming languages but is particularly prevalent in Java & Scala: it ensures that individual units of code (such as functions, methods, or classes) work correctly and helps maintain code quality, catch regressions, and improve the overall robustness of the software. Scala has an entire ecosystem dedicated to unit testing, something we might not have done extensively in other languages; we can design & build entire test suites that, thanks to Metals, are extremely easy to execute and debug.

2. Versioning and IDEs

Also, we’ll be using VS Code along with the Metals extension for this segment. However, there are more options for writing Scala code:

Although we can also use Scala 2 for some of the examples covered in this segment, it’s best to use Scala 3 since the latter contains many powerful improvements over Scala 2.

Preparing our environment

Although environment setup in Scala is not as straightforward as in other languages, we have some great tools to aid us in the process: we will make sure to have the following components ready before starting to write code:

- The Scala 3 language.

- A Scala 3 build tool, in this case, sbt.

- An IDE supporting Scala 3 syntax (in this case, VS Code).

- An IDE productivity tool, in this case, Metals.

1. Installing Scala 3 & sbt using Coursier

For Scala 3 installation, we’ll use a special tool called Coursier. This tool is a package & artifact manager that will:

- Install a JVM if none is present.

- Update the

JAVA_HOMEandPATHenvironment variables. - Add

~\AppData\Local\Coursier\data\bintoPATH. - Install the following packages:

ammonitecscoursierscalascalacscala-clisbtsbtnscalafmt

- Download & install the Simple Build Tool (sbt).

To begin, we’ll do the following:

- Download the latest release of

Coursiermatching our operating system. - Execute the installer.

- Add

CoursiertoPATHin case we missed it. - Setup our Scala environment running the following in PowerShell:

Code

cs setup --jvm adopt:11To verify our installation, we can use the following commands:

Code

java -version

scala --version

sbt aboutWhich should print the following:

Output

java version "20.0.1" 2023-04-18

Java(TM) SE Runtime Environment (build 20.0.1+9-29)

Java HotSpot(TM) 64-Bit Server VM (build 20.0.1+9-29, mixed mode, sharing)

Scala code runner version 3.2.2 -- Copyright 2002-2023, LAMP/EPFL

This is sbt 1.8.2Now that our installation is complete, we can install our IDE.

2. Installing VS Code

If we don’t yet have VS Code installed, we can get it from the official downloads page. We need to select the Windows 8, 10, 11 executable and wait for it to download. When the installation is complete, we can verify by opening the Visual Studio Code application directly from the Windows start menu. A detailed configuration guide for VS Code is out of the scope of this article but can be consulted on the VS Code official documentation site.

3. Installing Metals for VS Code

Once we have Scala 3, sbt, and VS Code installed, we will proceed to install the Metals VS Code Extension:

- Open VS code and head to the Extensions menu in the left panel. We can also open the Extensions menu by using the shortcut Ctrl + Shift + X or by opening the command palette by typing F1 and searching for Extensions: Install Extensions.

- We will search for

Scala (Metals), maintained by Scalameta, and install and enable it. We can also get the extension using this link.

Now that everything’s in place, we’re ready to start configuring our working environment.

The Scala REPL

As with many programming languages, Scala provides a REPL (Read-Evaluate-Print-Loop), a tool for evaluating expressions in Scala.

A Scala REPL can be opened from anywhere by using the following command:

Code

scalaOutput

Welcome to Scala 3.2.2 (11, Java OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM).

Type in expressions for evaluation. Or try :help.We can then input any expression we’d like to evaluate:

Code

println("Hello Scala")Output

Hello ScalaAlthough most of the code we’ll be writing will be inside Scala files, we can also use the REPL to quickly evaluate any expression on-the-fly.

Creating a new project

A typical Scala 3 generalized workflow consists of the following steps:

- Create a project folder.

- Create a project using sbt and a selected template (can be external or our own).

- Import our project’s main

build.sbtfile. - Write our Scala 3 code in a file appended by the

.scalaextension. - Compile & run our Scala 3 source file using sbt.

- Test our source code if a test suite is included in our project.

- Debug as per required.

We’ll follow each step in detail.

1. Creating a project

The first step is to create a project folder, where our project will reside:

Code

cd Documents

New-Item -ItemType Directory -Path scala-for-beginners

cd scala-for-beginnersWe can then create our project using a predefined template. Templates in sbt are predefined project structures or scaffolding that can be used as a starting point for new projects. Templates provide a convenient way to set up common project configurations, directory structures, and build settings.

There are several templates available for Scala sbt, including:

- Basic Template: This template provides a simple project structure with minimal configuration.

- Giter8 Template: Giter8 is a project templating tool that generates projects from templates hosted on GitHub. It allows us to choose from a wide range of community-maintained templates.

- Play Framework Template: Play Framework is a web development framework for Scala. This template creates a Play project with the necessary configurations and directory structure.

For this segment, we’ll be using the basic template. Once we’re in our project folder, we can execute the following command in PowerShell:

Code

sbt new scala/scala3.g8This will create a new project based on the Scala 3 seed template. It’s important to use scala3. Otherwise, a project using Scala 2 will be created.

We will then need to provide a name for our project when prompted:

Code

name [Scala 3 Project Template]: scala-for-beginnersThis will create one main folder with the name of our project, as well as multiple subfolders.

2. The directory structure

If we take a look inside our main project folder, we’ll see the following directory structure:

scala-for-beginners/

│

├── project/

│ ├── build.properties

│ └── plugins.sbt

│

├── src/

│ ├── main/

│ │ ├── resources/

│ │ └── scala/

│ │ └── Main.scala

│ │

│ └── test/

│ ├── resources/

│ └── scala/

│ └── MainSpec.scala

│

├── build.sbt/

├── .gitignore/

└── README.mdLet us explore each component in detail:

scala-for-beginners/: Is the root directory of our sbt project, named after the project name.project/: Contains sbt build configuration files.build.properties: Specifies the sbt version to be used for the project.plugins.sbt: Contains sbt plugin dependencies for the project.

src/: The source code directory, containing both main and test code.main/: Contains the main application code and resources.scala/: Contains the main Scala source code files.Main.scala: A sample Scala source file (not required to be namedMain; it’s just a convention to call the file containing the main methodsMain.scala).

test/: Contains the test code and resources.scala/: Contains the Scala test source code files.MainSpec.scala/: A sample Scala test source file.

build.sbt: The main sbt build configuration file, where we define project settings, the Scala version we’re using, library dependencies, and other build-related configurations. This file is extremely important and should always be located under the root directory..gitignore/: A sample.gitignorefile if we’re working with code versioning tools such as GitHub or GitLab.README.md: A samplereadmefile that should be included as an entry point to our project.

There are three directories/files we’ll usually modify during project development:

src/: This directory is meant to be modified and contains our source code.build.sbt: This file is intended to be modified if required..gitignore,README.md: These, of course, are intended to be modified since the already provided are just templates.

Apart from this base structure, we’ll include one additional element. For this, we will head to scala-for-beginners/src/ and create a new folder called worksheets. We will then cd into our new directory, and create a new file called MyExamples.worksheet.sc; we’ll see what this is in a moment.

3. Basic build configuration

When we created our project, a build.sbt file was also generated; this is the main build file for our application, and contains a structure like such:

Code

val scala3Version = "3.2.2"

lazy val root = project

.in(file("."))

.settings(

name := "scala-for-beginners",

version := "0.1.0-SNAPSHOT",

scalaVersion := scala3Version,

libraryDependencies += "org.scalameta" %% "munit" % "0.7.29" % Test

)This file is intended to be modified; here, we can add dependencies, packages, and the Scala version we’re using for this project.

Let us break this down in more detail:

scala3Version: The scala version we’re using for our project.libraryDependencies: The key denoting the packages we plan to install in our project. A dependency can be added by simply appending a newkey := dependencyentry:

Code

libraryDependencies += "org.typelevel" %% "cats-core" % "2.7.0"Where:

org.typelevel: Is the organization or group ID of the library, typically representing the package structure. In our case, it’s the group ID for the Cats library.%%: Is ansbt-specific shorthand that automatically appends the Scala binary version (e.g., 3.20 for Scala 3.20) to the library’s name. This helps us fetch the correct library version compatible with our project’s Scala version.cats-core: Is the library name or artifact ID. In our case, it’s the core module of the Cats library.%: Separates the library’s organization, name, and version in the dependency definition. It’s used to build the complete dependency string.2.7.0: Is the library version we want to include in our project. It represents the specific release of the Cats library we’ll be using.

4. Working with Scala worksheets

A couple of minutes ago, we created a new file called MyExamples.worksheet.sc. This file is a worksheet Scala file and will let us evaluate Scala code snippets incrementally as if we were using the Scala REPL.

Scala Worksheets use the .sc extension, and unlike a typical .scala file, they’re not compiled but run by the interpreter in real-time.

Worksheet files can be located in the following directory:

projectname/src/worksheet/MyExamples.worksheet.scThe name structure must be the following:

- Start with the parent directory name, followed by a dot.

- Include worksheet

keyword. - End with

.scextension.

Whenever we write code in the worksheet.sc file and save it, the Scala interpreter will automatically run the code and produce the output inside the file.

Let us write a simple line in our newly-created worksheet and check its output:

Code

println("Hello, World")Output

println("Hello, World")

// Hello, WorldIf there’s any problem with our code, the compiler will throw an error.

5. Working with Scala source files

Scala files have the .scala extension and are compiled when we run the project if a main class exists.

We can have multiple .scala files with multiple classes, objects, and methods inside, but there will be one main class required for each project. This class should be treated as the entry point to our application.

5.1 Programs

We’ll see classes & objects in more detail later on, but for now, we must know that a main class can be defined using three different ways:

- Using a

Mainobject with Java-like syntax. - Using a

Mainobject which extends App, and saves us the Java-like syntax. - Using the

@mainannotation.

5.1.1 Using a Main object with Java-like syntax

This method includes a Main object along with a main method sticking to Java syntax:

Code

object Main {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

println("Hello, world!")

}

}If we compare this with a Java main Class & method, we can see it’s very similar:

Code

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args){

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

}This way of declaring Main objects is too verbose, defeating one of Scala’s purposes compared to Java: Creating a more concise language.

5.1.2 Using a Main object extending App

This is a more concise version of the above since we can effectively save the Java-like syntactic verbosity, but we still declare a Main object:

Code

object Main extends App {

println("Hello, world!")

}As we’ll see later on, the extends keyword extends the behavior of A with B, in this case, App with Main; by extending the App trait, we automatically get a main method for our application, so we don’t need to define it ourselves. We can write our application’s code directly within the Main object body, and the App trait executes it.

One thing to note is that when using object Main extends App, our application’s code will be executed when the Main object is run. This approach was commonly used in Scala 2, but it’s worth noting that the App trait relies on the DelayedInit feature, which is deprecated in Scala 3. For new Scala 3 projects, it is recommended to use the @main annotation to define a main method or implement a main method within an object, as these approaches are more concise and do not rely on deprecated features.

5.1.3 Using the @main annotation

This is the more concise method since we don’t even need to define a Main object or method explicitly:

Code

@main def hello(): Unit = {

println("Hello Scala")

}When we annotate a method with @main, the Scala 3 compiler automatically generates a wrapper object with a main method that calls our annotated method. This wrapper object serves as the entry point for our application and does not require any explicit main method declaration.

If we’re wondering which one to use, it’s really up to us to decide. However, the preferred method is the last one since it’s more concise and extremely easy to read.

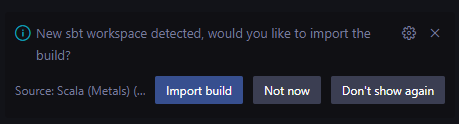

6. Opening our project in VS Code

We will need to open our project in the root directory. This directory can be found by locating the build.sbt file, which will be the main build file for our project. We can then simply open VS Code and select import build:

When we import the main build, some additional folders will be created in our root directory:

scala-for-beginners/

│

├── .bloop/

├── .bsp/

├── .metals/

└── plugins.sbtWe’ll not be working directly with these folders. However, it’s important to know they belong to the Metals extension and the sbt compiler.

7. Compiling and running a Scala project

If we have our .scala file, we can compile it and run it using sbt:

- Go to our project’s main directory.

- Initialize an

sbtprompt. - Execute the

runcommand.

This command will run only if a main class is associated with our project. Else, it will throw an error.

We can try this command on our Main.scala predefined template, which should look like such:

Code

@main def hello: Unit =

println("Hello world!")

println(msg)

def msg = "I was compiled by Scala 3. :)"Code

runOutput

[info] running hello

Hello world!

I was compiled by Scala 3. :)

[success] Total time: 0 s, completed May 12, 2023, 5:34:12 PMThis should run our main source file, and create a new directory under our project’s root folder:

scala-for-beginners/

│

└── target/The target/ folder contains all the information produced by the compiler on our first compilation. This includes the Java Bytecode files, which are under scala-for-beginners\target\scala-3.2.2\classes.

Files with the .class extension are Java Bytecode files that can directly run on the JVM.

8. Working with the SBT shell

The build tool we installed earlier (sbt) provides a shell we can access to perform several operations on our Scala project, such as compiling, executing, testing, debugging, and more. We can access the sbt shell whenever we’re under an existing sbt project (that is, under the root folder of our project).

An sbt instance can be executed by using the following command:

Code

sbtOutput

[info] welcome to sbt 1.8.2 (Oracle Corporation Java 11)

[info] loading project definition from C:\Users\Pablo\OneDrive\Documents\Blog\computer-science\scala-3-for-beginners\scala-for-beginners\project

[info] loading settings for project root from build.sbt ...

[info] set current project to scala-for-beginners (in build file:/C:/Users/Pablo/OneDrive/Documents/Blog/computer-science/scala-3-for-beginners/scala-for-beginners/)

[info] sbt server started at local:sbt-server-6ea3b4cc30af6310f6a2

[info] started sbt server

sbt:scala-for-beginners>Any command we execute inside of this shell will be in reference to our newly-created project.

There are two main commands we’ll be using extensively throughout this segment:

run: Compiles and runs a main class, passing along arguments provided on the command line.test: Executes all tests.

If we have questions about any command in sbt, we can execute the following command:

Code

help <command_name>For example:

Code

help projectOutput

project

Displays the name of the current project.

project name

Changes to the project with the provided name.

This command fails if there is no project with the given name.

project {uri}

Changes to the root project in the build defined by `uri`.

`uri` must have already been declared as part of the build, such as with Project.dependsOn.

project {uri}name

Changes to the project `name` in the build defined by `uri`.

`uri` must have already been declared as part of the build, such as with Project.dependsOn.

project /

Changes to the initial project.

project ..

Changes to the parent project of the current project.

If there is no parent project, the current project is unchanged.

Use n+1 dots to change to the nth parent.

For example, 'project ....' is equivalent to three consecutive 'project ..' commands.We can also consult the full sbt documentation here.

Basic syntax

Scala syntax is similar to Java’s. However, it’s considerably less verbose, more compact & concise, & more expressive. Especially Scala 3 possesses several syntax improvements over its predecessor, Scala 2.

1. Commenting

There are two ways we can use to comment in Scala:

- Single-line commenting

- Multi-line commenting

1.1 Single-line commenting

Single-line commenting is done via double forward slashes //:

Code

// Single commenting1.2 Multi-line commenting

Multi-line commenting is achieved by enclosing our comment in single forward slashes / and asterisks *:

Code

/*

Multi-line

commenting

*/2. Immutable variables

Variables in Scala can be mutable or immutable. Upon starting to write Scala code, we might be tempted to use mutable variables since this might seem “easier” at first glance but is not recommended in functional programming, and we’ll see why in more detail. For now, we’ll focus exclusively on immutable variables and only briefly mention mutable variables.

There are two main ways we can declare immutable variables in Scala 3, depending on the evaluation strategy we’re after:

- Using

def: Lazy evaluation (this is not exactly a variable. Instead, it’s a function declaration, but it can be used to declare variables also). - Using

val: Eager evaluation.

2.1 Lazy evaluation

Lazy evaluation is an evaluation strategy that delays the evaluation of an expression until its value is needed. This means we can declare a variable or function, and the compiler will not evaluate until explicitly called.

Lazy evaluation in Scala for variables can be achieved by using the def keyword:

Code

def mylazyvar = 21We might recall that the keyword def is sometimes used to declare functions in other languages, and that also applies to Scala; we’re essentially defining a method with no parameters and a returning value.

2.2 Eager evaluation

Eager evaluation is the opposite of lazy evaluation; it evaluates the expressions upon declaration. We can achieve this in Scala by using the val keyword.

We can declare a variable using the following syntax:

Code

// Eager evaluation using val

val myeagerval = 313. Mutable variables

We mentioned that declaring mutable variables in Scala and functional languages is not a good idea. This is because of multiple reasons:

- Predictability and Understanding: When we use immutable data, it’s easier to reason about our code because we don’t have to worry about data changing unexpectedly. Once a

valis set, we know it will stay the same. - Concurrency and Parallelism: Immutable data is inherently thread-safe, meaning it can be used across multiple threads without synchronization. This is a big advantage when dealing with concurrent or parallel processing because it avoids issues with data inconsistency and race conditions.

- Purity: Functions in functional programming are usually pure, meaning they don’t have side effects, and their output depends solely on their input. This is easier to achieve with immutable data.

In short, working with immutable variables results in safer and more predictable behavior upon our application’s execution.

However, there are instances when we might want to declare mutable variables, for example, when dealing with iterators that include an accumulator variable or when performance is a concern and creating new immutable objects would be costly regarding memory or processing time.

We use the var keyword to declare a mutable variable:

Code

// Eager evaluation using var

var myeagervar = 32

// Reassign variable

myeagervar = 33

// Print final evaluation

println(myeagervar)Output

// 33As with val, declarations with var are eager, meaning they will be evaluated when declared.

4. Printing & strings

Printing in Scala can be achieved using two main methods:

println()print()

The first one is short for “print line” and adds a new line character at the end of each print statement, while the second one does not:

Code

// Declaring a simple variable

val myString = "Howdy hey"

// Using println

println(myString)

// Using print

print(myString)Since we’re working inside a workbook, we’ll be unable to see the difference between the two, but when compiling, the first adds the new line, while the second does not. This means that if we insert two println() statements in consecutive order, they will be printed in new lines, while two print() statements will print the content in the same line:

Output

Howdy hey

Howdy hey

Howdy heyHowdy heyPrinting variables to stdout is often accompanied by a combination of strings and variables. Scala provides a handy mechanism called string interpolation, which allows us to mix both types, similar to what f-strings in Python would do:

Code

// Declaring a simple variable

val myImportantVal = 1000

// Print using string interpolation

println(s"This is one very important value: ${myImportantVal}")Output

// This is one very important value: 10005. Optional braces & semicolons

Scala 3 has brought a really useful improvement to the table: The capacity to declare anything without the use of two components:

- Curly braces

- Semicolons

This is a relevant improvement since it makes the code clearer and easier to read; we rely on the indentation to provide structure to our declarations. However, this is optional; thus we can or cannot omit both components, and the result will be the same:

Code

// Declaring a function including braces & semicolons

def myFun1 = {

7 * 7;

}

// Declaring a function omitting braces & semicolons

def myFun2 =

7 * 7We’ll see function declarations in a second, but the relevant thing here is to illustrate that both options are plausible; it simply depends on personal preference.

6. Indentation

Like its predecessor Scala 2, Scala 3 does not rely on indentation as part of its syntax. However, since curly brackets are not optional in Scala 3, indentation provides a visual guideline on variable & function declarations (blocks in general).

Because of this, we can declare a function without indenting:

Code

def myUnindentedFun(a: Int): Unit =

println(a)

def myIndentedFun(a: Int): Unit =

println(a)

myIndentedFun(7)

myUnindentedFun(7)As expected, both will produce the same result:

Output

// 7

// 7This also applies to other definitions when when we’re using curly brackets {} to denote blocks:

Code

val myUnindentedVar: Int =

{

val a = 1

a

}

val myIndentedVar: Int =

{

val a = 1

a

}Even though the first approach is awful, it works as expected:

Output

myIndentedVar: Int = 1

myUnindentedVar: Int = 17. Functions

Functions are a core part of Scala’s architecture; they let us abstract methods in multiple ways. Functions possess a wide variety of properties and can be often declared using combinations of syntactic sugar components.

A function in Scala is defined using the keyword def.

There are 3 main types of functions:

- Named functions without arguments

- Named functions with arguments

- Anonymous functions

7.1 Functions without arguments

As we’ve already seen, functions in Scala can be declared without any argument:

Code

// Declaring a function without arguments

def simpleFun = 7 * 7This function simply evaluates the multiplication operation and returns its value.

7.2 Functions with arguments

The more common use-case of functions in Scala is by including arguments that can be evaluated:

Code

// Declaring a function with arguments

def moreElaborateFun(x: Int, y: Int) = x * yHowever, in this case, we do need to include types for our arguments. Else, the compiler will return an error (we’ll see type definition in a second).

Functions can be declared using one-line expressions or can also be continued in the next lines:

Code

def multilineFunction(x: Int, y: Int) =

val myvar_1 = 14

val myvar_2 = 7

x + y + (myvar_1 * myvar_2)We can then call our function:

Code

multilineFunction(5, 5)And it will return the expected result:

Output

res0: Int = 1087.3 Anonymous functions

It might be of no surprise that Scala supports and encourages anonymous functions, also called literal functions, if they’re required or could simplify our code.

Anonymous functions can be declared using the following syntax:

Code

val myNewInt = (a: Int, b: Int) => a * bHere, we’re declaring a new variable, myNewInt, that will hold the resulting evaluation of our anonymous function, (a: Int, b: Int) => a * b.

The difference with a named function is that in the latter, we declare a function explicitly and separately from our variable assignment, then evaluate and assign.

In the case of an anonymous function, we do both evaluations in one single step. So when we call our variable with the two parameters, a and b, we evaluate the anonymous function and assign it:

Code

println(myNewInt(5, 7))Output

// 35Of course, here we’re doing a fairly simple product operation, but anonymous functions can be extremely handy when we want to apply more complex operations to variables.

8. Blocks

Blocks in Scala are a scope-delimitation mechanism to group multiple expressions or statements together. They are declared using curly brackets {} and serve several purposes, including scoping and variable visibility; when we’re defining variables, the Scala compiler provides a dedicated namespace.

If we recall, variables in Scala are immutable, meaning we need to get creative with naming conventions if we’re working with extensive programs. What blocks allow us to do, is to create a restricted namespace, where we can use variable names that were used outside the block without any problem:

Code

{

val inside_1 = 14

val inside_2 = 21

}

// Try to reference inside variable outside block

inside_2Output

Not found: inside_2This error is thrown since the variable is not in the global scope where it’s being referenced.

Blocks are not common as standalone elements but are usually employed in variable or function definitions:

Code

// Declare a variable using blocks

val my_extense_var = {

val a = 5 * 4

val b = 7 * 2

b

}Here, we’re declaring an immutable variable using a block that contains a set of expressions, including two additional variables, a, b, and the eventual return of the last variable, b.

This might seem weird, but it’s part of Scala’s magic; we can define variables inside variables. What’s cooler is that we don’t even need to declare a return statement. In fact, Scala encourages not to use return statements since, by default, the last evaluated expression inside any block or function is returned.

9. Type declaration

Up until now, we have not included much data type declaration. But wait, didn’t we say that Scala was a strong statically typed language? Yes, indeed, but the compiler is smart enough to infer the data types on compile time in some cases (there are exceptions, for example, with lists or other more elaborate structures, where we have to explicitly declare the types of the variables inside our list).

However, we’re talking about a strong statically typed language here, so it’s best practice to try to always explicitly declare the data types. This is because, unlike other languages like Python, Scala is strict in terms of which operations can be performed with which data types, and it might be easier if we have a clear sense of what data types we have before performing any operation on our variables.

Type declaration is performed using the colon symbol :, followed by the type we’re using:

Code

// Declaring a variable with its type

val myval_1: Int = 14

// Declaring a function with its type

def myfun_1: Int = 7 * 7

// Declaring a function with its type, including its arguments

def myfun_2(x: Int, y: Int): Int = x * yBasic data types

Scala encourages type-driven development simply because it possesses a rich type system that lets us perform multiple manipulations and even create our own very complex type hierarchies, similar to what we would do with classes & objects in an OOP approach (Scala combines these two approaches seamlessly).

1. An introduction to type-driven development

Having discussed data type declarations, it’s helpful to consider the data types available in Scala. This is because Scala programming can and should utilize types and type hierarchies extensively, a practice often referred to as type-driven development (TDD). Scala’s robust type system, while not strictly adhering to the Hindley–Milner (HM) system found in some purely functional languages, allows for powerful type inference.

The concept of type-drive development is sometimes hard to grasp since we might be accustomed to other styles, such as OOP. Let us try to explain this using two examples:

- Object-Oriented Programming (OOP): We’re building a toy car using LEGO blocks. The car’s wheels are designed to roll, the doors can open and close, and so on. The blocks (objects) have specific shapes and sizes, and each has its own role in the structure. In essence, each object carries both data (the specifics of the block) and behavior (what the block does in context).

- Type-Driven Development (TDD): We’re putting together a jigsaw puzzle. Each piece (type) has a specific shape, pre-defined where and how it fits into the overall picture. Before adding a piece, we know exactly what shape we’re looking for due to the constraints provided by the pieces we’ve already placed.

If this was still confusing, we might want to start cooking a pizza to better illustrate:

- Object-Oriented Programming (OOP): We’re cooking freestyle. We have ingredients (objects) and know what to do with them (methods). We decide on the fly what to do next, depending on how the dish is coming along. We might add onions, then decide to season with some peperoncino or maybe add some garlic.

- Type-Driven Development (TDD) We’re now following a recipe. We have a list of ingredients (types) and specific steps (functions) outlined. We follow the recipe step by step. The recipe tells us when to chop the onions when to add them, and when to season with peperoncino.

In short, both cooking styles can result in a delicious pizza, but they use different approaches; with OOP, we have flexibility but might make mistakes or changes along the way. With TDD, we have a solid plan that ensures the dish turns out as expected, provided we follow the recipe correctly.

However, this doesn’t mean that TDD is rigid (in the context of limited or not flexible). On the contrary: The approach is flexible but under our own terms, which reduces the potential errors that might arise with the preparation of a pizza; it ensures that the pizza will turn out to be a pizza and not a suspicious blob of dubious precedence.

Of course, since we usually define the general rules in the first place, TDD requires technical knowledge of what can and cannot be done with certain types provided by the language, in this case, Scala. This knowledge is called type-system knowledge and is especially relevant in languages with rich type systems like Scala.

Now that we have more clarity about TDD, we can describe Scala’s type system.

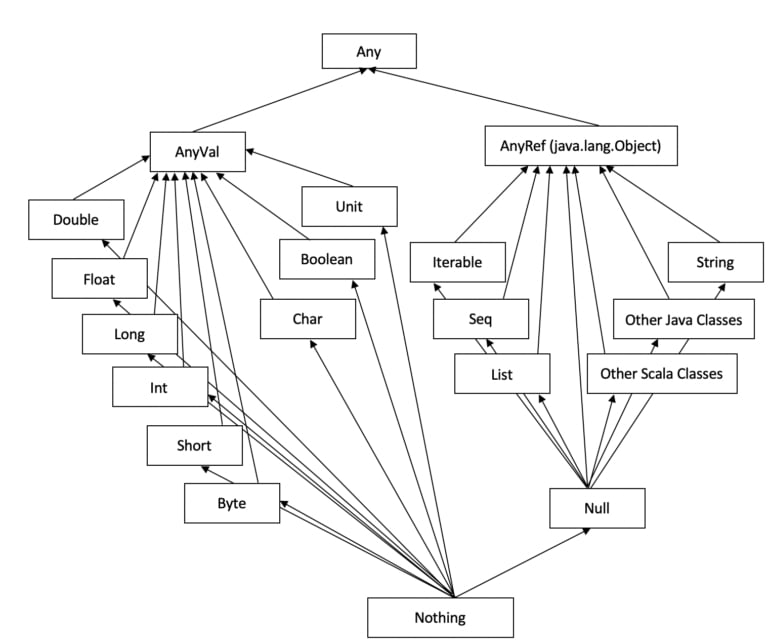

2. Scala’s type system overview

Scala follows a hierarchical type system that contains its own defined types, as well as some inherited types from Java:

Let us break this hierarchy down into its individual components:

Any: The supertype of all types, defining methods like==,!=, andtoString.AnyValrepresents value types. These includeDouble,Float,Long,Int,Short,Byte,Char,Unit, andBoolean. They correspond to primitive types in Java and cannot benull.AnyRef: Represents reference types. All non-value types are defined as reference types. This is equivalent tojava.lang.Object.

Null: A subtype of allAnyReftypes, and its only instance isnull.Nothing: A subtype of all other types, with no instances. It’s used to denote abnormal termination and as a type for empty collections.

So, in short:

AnyVal: Represents value types. They are lightweight, non-nullable, and usually have better performance characteristics.AnyRef: Represents reference types, meaning all types that are subclasses ofjava.lang.Objectin Java. They are typically more complex, can benull, and include all user-defined and most built-in types.

Let us start from the more basic types and build from there.

3. Numeric types (AnyVal)

Scala provides six main numeric types, from Byte to Double. From bottom to top:

ByteShortIntLongFloatDouble

3.1 Byte

A Byte in Scala represents an 8-bit signed integer. Its value range is from -128 to 127. We can declare a Byte variable using the following syntax:

Code

val myByte: Byte = 127Since we’re dealing with a Byte type, we can perform arithmetic operations only with another Byte-type variable: Arithmetic operations in Scala return an Int value as a result. This is why these are not possible:

Code

// Declare a Byte

val myByte: Byte = 127

// Impossible operations with Byte

val myByte_2: Byte = myByte - 7

val myByte_3: Byte = (myByte - 7.toByte)Output

Found: Int

Required: Bytemdoc

val myByte: ByteWhile these are possible:

Code

// Possible operations with Byte

val myByteToInt = myByte - 7

val myByte_2: Byte = (myByte - 7).toByteOutput

myByteToInt: Int = 120

myByte_2: Byte = 1203.2 Short

A Short is a 16-bit signed integer data type. It has a value range from -32768 to 32767. We can declare a Short variable using the following syntax:

Code

val myShort: Short = 32767The same Byte rules apply to this data type.

3.3 Int

The Int type is probably the more well-known data type when referring to integer values. It represents a 32-bit signed integer data type. It has a value range from -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647. The Int type is the default type when we’re declaring an integer variable without its explicit type:

Code

// Declare an Int with explicit type

val myIntExp: Int = 1

// Declare an Int with inferred type

val myIntInf = 1Here, both declarations will result in the same data type:

Output

myIntExp: Int = 1

myIntInf: Int = 1It’s true that Int is the default integer value type in Scala, but it’s not necessarily the most adequate when dealing with large numbers. If we want to define a number larger than what Int lets us do, we must use the Long type. This is true for all previous cases: We need to have clarity on what we’re expecting from our variable since integer arithmetic can overflow and underflow without warning if the result of an operation exceeds the maximum or minimum value.

3.4 Long

The Long type is a 64-bit signed integer data type. It has a value range from -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807. The Long type is used when the value to be stored exceeds the range provided by Int.

A Long value can be declared the same as with previous examples, but with the difference that we must append the L character (for Long) at the end of the number:

Code

val myLong: Long = 9223372036854775807LWe append this L suffix because, by default, Scala treats integer literals as Int. The type annotation : Long tells Scala that the variable is of type Long, but it doesn’t change how Scala interprets the literal number.

Consequently, this would result in an error:

Code

val myLong: Long = 9223372036854775807Output

integer number too large3.5 Float

The Float type is a 32-bit floating point number. This means it can represent decimal numbers but with a limit to the amount of precision. It’s sometimes referred to as a single-precision floating-point number in the IEEE 754 standard and has a precision of about seven decimal digits.

We can declare a Float variable as follows:

Code

val myFloat: Float = 3.141592653589793238462643383279502884197We can see that even though we include the complete decimal precision for ![]() , we only get up to 7 decimal numbers in return:

, we only get up to 7 decimal numbers in return:

Output

myFloat: Float = 3.1415927We can also declare decimal numbers using scientific notation:

Code

val myFloat_2: Float = 2.102030E1Which will result in the following:

Output

myFloat_2: Float = 21.0203If we’d like decimal numbers with increased precision, we can instead use a Double type.

3.6 Double

The Double type represents a 64-bit double-precision floating-point number. This type can be used to store decimal numbers with a larger range and precision than Float.

We can declare a Double type variable using the following syntax:

Code

val myDouble: Double = 3.141592653589793238462643383279502884197Which will result in the following:

Output

myDouble: Double = 3.141592653589793As we can see, we get a precision of about 15 decimal numbers.

With this, we wrap up the numeric types under AnyVal. We can now proceed to non-numeric types.

4. Non-numeric types (AnyVal)

Non-numeric types under AnyVal in Scala include the following subclassification:

- Textual types

BooleantypeUnittype

In the case of AnyVal, the only textual type is Char, while the boolean type is the well-known True / False type.

4.1 Char

A Char is a 16-bit unsigned Unicode character type. It can represent any character in the Unicode character set, including ASCII and other characters from various languages worldwide. A ‘Char’ ranges from U+0000 to U+FFFF.

Because a Char represents integer Unicode code point values, we can treat them as such, meaning we can perform arithmetic & relational comparison operations:

Code

// Declare some chars

val myChar_1: Char = 'a'

val myChar_2: Char = 'b'

val myChar_3: Char = '1'

// Perform arithmetic operations with chars

myChar_1 > myChar_2

myChar_1 < myChar_2

myChar_1 >= myChar_2

myChar_1 <= myChar_2

myChar_1 != myChar_2

myChar_1 + myChar_2

myChar_1 - myChar_2

myChar_1 * 1

myChar_2 * 1

myChar_3 * 1Output

// res5: Boolean = false

// res6: Boolean = true

// res7: Boolean = false

// res8: Boolean = true

// res9: Boolean = true

// res10: Int = 195

// res11: Int = -1

// res12: Int = 97

// res13: Int = 98

// res14: Int = 49A Char is represented as a 16-bit unsigned integer in memory. This means it can take on a value between 0 and 65535. These numbers correspond to the Unicode values of the characters the Char can represent.

If we would like to convert a char to its unsigned integer type, we can do so:

Code

// Convert Char to Int

myChar_1.toIntOutput

res15: Int = 974.2 Boolean type

The Boolean type in Scala, as in any other language, can take one of two possible values:

truefalse

Keep in mind that in Scala, boolean values are declared in lowercase (in other languages, this might change):

Code

val myBoolTrue: Boolean = true

val myBoolFalse: Boolean = false4.2.1 Logical operators in Boolean variables

We can use logical operators on boolean types:

Code

// Boolean types

val myBoolTrue: Boolean = true

val myBoolFalse: Boolean = false

// AND Operator

myBoolTrue && myBoolTrue

myBoolTrue && myBoolFalse

myBoolFalse && myBoolTrue

myBoolFalse && myBoolFalse

// OR Operator

myBoolTrue || myBoolTrue

myBoolTrue || myBoolFalse

myBoolFalse || myBoolTrue

myBoolFalse || myBoolFalseWhich will result in the following:

Output

// res16: Boolean = true

// res17: Boolean = false

// res18: Boolean = false

// res19: Boolean = false

// res20: Boolean = true

// res21: Boolean = true

// res22: Boolean = true

// res23: Boolean = false4.3 Unit type

The Unit type is used when there is no meaningful value to return. It’s similar to the void keyword in other languages like Java or C++.

For example, suppose we have a function that evaluates a certain expression and prints it out to stdout without returning the actual value as a result of the evaluation. In that case, we can use the Unit return type as follows:

Code

def myFun(x: Int, y: Int): Unit =

val a = x + y

println(a)

myFun(1, 2)Output

// 35. Nothing type

Nothing is a subtype of every other type (including Null). It represents “no value at all“. There are no values of type Nothing. It’s used in Scala to signal abnormal termination. This is frequently used in methods with an abnormal exit, like throwing an exception.

We can define a function that throws an exception:

Code

def myErrorFun(x: Int): Nothing = x match {

case x:Int => throw new IllegalArgumentException(s"{s} is not of the correct type.")

}

myErrorFun(1)Output

java.lang.IllegalArgumentException: {s} is not of the correct type.The only constraint is that this function will need to throw an exception since the type Nothing cannot be defined as a return type of other types (e.g., Int, Double, etc.). In other words, we have to ensure that our function’s return type is an exception or something returning Nothing. There are other ways to manage the return of two potential types; for example, if the exception is not met and we return an Int instead. We’ll look at that later.

Control structures

Control structures are used to control the flow of execution of our program. Scala offers multiple ways to do this, but the two main ones are:

- Using the

if-elseconstruct. - Using pattern matching.

The first option is more simple & straightforward but limited, while the second one is slightly more elaborate but much more powerful regarding reach & capabilities.

Let us look at both.

1. Conditionals

Conditionals in Scala are mostly used to evaluate simple single statements. They consist of a simple if-else structure and can be nested if we need more conditions, although this is discouraged in favor of pattern matching.

Conditional statements can be written using two different ways:

Code

// Using no parenthesis and then

if a+b then c

else d

// Using parenthesis

if (a+b) c

else dLet us declare a simple function that verifies if an integer value is greater than another number:

Code

def getBiggest(x: Int, y: Int): Int =

if (x >= y) x

else y

getBigger(1, 2)

getBigger(4, 1)Output

res25: Int = 2

res26: Int = 4Multiple conditions can also be evaluated using two approaches:

- Logical operators

- Nested

if-elseconstructs

We can include more than one condition on a single if statement by using logical operators:

Code

def checkInBetween(x: Int, y: Int, z: Int): Boolean =

if ((y > x) & (y < z)) true

else false

checkInBetween(2, 3, 4)

checkInBetween(3, 2, 4)Output

res27: Boolean = true

res28: Boolean = falseWe can also nest multiple if-else statements for more elaborate tests:

Code

def checkSmallest(x: Int, y: Int, z: Int): Int =

if ((x <= y) & (x <= z)) x

else if ((y <= x) & (y <= z)) y

else z

checkSmallest(1, 2, 3)

checkSmallest(5, 2, 10)

checkSmallest(1, 1, 2)Output

res29: Int = 1

res30: Int = 2

res31: Int = 1Here, we only have one nested statement, so it’s fairly easy to read, but whenever we add more conditions, our code will get messier; the if-else construct was not designed for multiple tests. This is where pattern matching comes into play.

2. Pattern matching

Pattern matching might be one of the most powerful features in Scala; it lets us destructure and examine complex data types clearly and concisely, providing a mechanism to execute code conditionally based on the structure or values of the data. It also enables seamless matching of sequence types, with capabilities to inspect sequence length and element position.

These are just two more sophisticated use cases, but we can also match using simpler statements. We’ll start with a base definition using a code block:

Code

val match_using_anonymous = (x: Int) => x match {

case 1 => s"${x} is equals to 1"

case 2 => s"${x} is equals to 2"

case _ => s"${x} is neither 1 nor 2"

}

match_using_anonymous(1)

match_using_anonymous(10)Output

res32: String = 1 is equals to 1

res33: String = 10 is neither 1 nor 2Where:

_is a wildcard that matches any other value.

But this is a useless example, right? Who would want to check if a value is 1 or 2 using a pattern-matching implementation? Too much hustle, which can be simplified using a conditional construct.

That is correct. However, pattern matching is clearly not restricted to comparing integer numbers as we just did. In fact, this construct is much more powerful.

Since pattern matching can be used to deconstruct types, we can use it to check if a given class is a subclass of another class by trying to feed an animal, only if it’s a dog:

Code

// Define abstract Animal class with unimplemented methods

abstract class Animal:

val name: String

val age: Int

val species: String

def salutes: Unit

end Animal

// Define Human class extending Animal

class Human(val name: String, val age: Int) extends Animal:

val species: String = "human"

def salutes =

println(s"Hi, my name is ${this.name}, I'm ${this.age} years of age, and I'm a proud ${this.species}.")

end Human

// Define Doggo class extending Animal

class Doggo(val name: String, val age: Int) extends Animal:

val species: String = "doggo"

def salutes =

println(s"Woof woof!!, My name is ${this.name}, I'm ${this.age} years of age, and I'm a happy big ${this.species}.")

end Doggo

// Define a weird Animal subclass

class WeirdGuy(val name: String, val age: Int) extends Animal:

val species: String = "weird guy"

def salutes =

println(s"Howdy doody, partner! I'm ${this.name}, ${this.age} olde, and I'm somewhat of a ${this.species}. Why don't ya grab yerself a cold one and sit a spell, ya hear?")

// Instanciate

val Chad = new Human("Chad", 23)

Chad.salutes

val Napoleon = new Doggo("Napoleon", 5)

Napoleon.salutes

val Skeeter = new WeirdGuy("Skeeter", 20)

Skeeter.salutes

// Declare feeding function (is not a method, since it does not belong to Animal or any of its subclasses)

def feedAnimal(subject: Animal): String = subject match

case subject: Doggo => s"Here you go ${subject.name} big boy, take some bacon!"

case subject: Human => s"Hey my friend ${subject.name}, that bacon's not for you. Hands off please!"

case _ => "I don't know who or what you are, kindly leave my house or I'll call the police, my good sir."

// Feed the dog animals only

feedAnimal(Napoleon)

feedAnimal(Chad)

feedAnimal(Skeeter)Output

// Hi, my name is Chad, I'm 23 years of age, and I'm a proud human.

// Woof woof!!, My name is Napoleon, I'm 5 years of age, and I'm a happy big doggo.

// Howdy doody, partner! I'm Skeeter, 20 olde, and I'm somewhat of a weird guy. Why don't ya grab yerself a cold one and sit a spell, ya hear?

res37: String = Here you go Napoleon big boy, take some bacon!

res38: String = Hey my friend Chad, that bacon's not for you. Hands off please!

res39: String = I don't know who or what you are, kindly leave my house or I'll call the police, my good sir.Let us explain what’s happening in more detail:

- We first declare an

Animalabstract class (we’ll discuss them later in more detail) with some unimplemented methods. - We then declare three subclasses:

Human,Doggo, andWeirdGuy - Next, we implement their methods and create new instances for each subclass.

- Finally, we declare a feeding function that accepts an

Animalinstance and prints something tostdout, depending on the type of the subclass we’re including. Since abstract classes cannot be instantiated, our only options are:- To try to feed a

Doggo. - To try to feed a

Human. - To try to feed a

WeirdGuy.

- To try to feed a

Since we as humans can usually eat our own food, at least when we’re grown-ups, and it would not be the best idea to let a weird guy inside our house, we can assume that a doggo will be the only candidate to be fed.

We check if the Animal is one of the two and decide whether to feed it or not. Lastly, we leave any other options at the end, including a not-so-friendly message.

This is just a simple pattern-matching example, but a wide variety of operations can be done using the match-case construct.

3. Loops

Loops in functional languages are sometimes not implemented in the traditional sense, at least not exactly. One of the characteristics of the functional style is that it discourages the use of for loops. This is because:

- Loops can and usually will involve a mutation of some variable(s). This, in turn, can result in impure implementations with side effects associated.

- Scala provides more powerful and concise ways to loop over things without explicitly writing a

forloop, or even worse, a set of nested loops that quickly becomes unreadable, confusing, and bug-prone. - Functional programming is more declarative than imperative, focusing on the “what” rather than the “how“. Using higher-order functions or recursion instead of

forloops is more in line with this style, as it focuses on the result of the operation rather than the specific steps needed to achieve it.

In short, using loops in Scala is like building a house with the wrong, expensive tools; we’re better off using Python since, in that case, it’s “cheaper” to learn, if that makes sense.

We’ll briefly mention loops to illustrate why they’re discouraged and what functional approaches we can use instead.

3.1 while loops

A while loop loops through a block of code as long as a specified condition is true. This specified condition usually involves some kind of variable mutation since, otherwise, the condition is never met, and the loop goes forever and ever.

We can define a simple while loop that checks for even numbers when dividing an initial number by 2:

Code

// Declare a simple integer mutable variable

var y: Int = 100

// Declare a while loop

while (y % 2 == 0)

println(s"${y} is still even")

y /= 2Output

// 100 is still even

// 50 is still evenNow for the functional approach, we implement a tail-recursive function:

Code

// Declare a functional-style equivalent

def checkEven(y: Int): Unit =

if (y / 2 % 2 != 0) println(s"${y} is still even")

else checkEven(y / 2)

checkEven(100)Output

// 50 is still evenIn this last approach, we don’t care for the even intermediate numbers; we just care for the last even number when divided by 2.

At first, the recursive approach might seem more confusing, but we’re saving ourselves a potential future headache: We don’t mutate any variable; thus we don’t need to track its development over time.

3.2 for loops

In contrast to while loops, for loops loop over their body a defined number of times. These are helpful when we have a known range of values to cover. A typical for loop can be declared using the following syntax:

Code

// Declare a for loop

for (x <- 1 to 10)

println(x)Output

// 1

// 2

// 3

// 4

// 5

// 6

// 7

// 8

// 9

// 10Now for the functional-style equivalent:

Code

// Declare a functional-style equivalent

def printInteger(x: Int): Unit =

if (x == 10) println(x)

else printInteger(x + 1)

printInteger(1)Output

// 103.3 for comprehensions

In contrast to the previous two approaches, for comprehensions are syntactic constructs to build a new collection by applying some operations to each element of an existing collection.

We might already know comprehensions from other languages, such as Python:

Code

# Comprehensions in Python

# List comprehension

mylist = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

mylist_squared = [x**2 for x in mylist]

print(mylist_squared)Output

[1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]In Scala, things are similar:

Code

// Declare a list

val mynumbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

// Apply squared and create new list

val mynumbers_squared: List[Int] = for (n <- mynumbers) yield n * nOutput

mynumbers_squared: List[Int] = List(1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81)In this example, n <- numbers is a generator that generates a new n for each element in numbers. yield n * n then creates a new element for the new list.

As with list comprehensions in Python, we can also add conditions to for comprehensions in Scala:

Code

// for comprehensions with conditions

val numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

// Apply modulus and filter by odd & even numbers

val numbers_odd: List[Int] = for (n <- numbers if n % 2 != 0) yield n

val numbers_even: List[Int] = for (n <- numbers if n % 2 == 0) yield nOutput

numbers_odd: List[Int] = List(1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

numbers_even: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8)4. Exception handling

Exception handling in Scala is similar to that in Java and other languages, with try, catch, and finally blocks used to handle exceptions.

We can declare a simple exception-handling implementation by using the following syntax:

Code

def parseStringToInt(x: String): Unit =

try

val parsed: Int = x.toInt

println(parsed)

catch

case e: NumberFormatException => println(s"Couldn't parse '${x}' to an integer.")

parseStringToInt("7")

parseStringToInt("a")Output

// 7

// Couldn't parse 'a' to an integerThere are other methods we can use to catch exceptions:

- Using the

scala.util.Trymethod. - Using

Option - Using

Either

However, we’ll not review those in this segment.

Collections

Collections in Scala are simply containers of things. They can be sequenced, linear sets of items like List, Tuple, Option, Map, Set, etc.

1. List

A List is an ordered collection of elements. It’s a linear sequence that can contain duplicate elements. Elements in a list can be accessed using an index.

Code

val myIntList: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

val myStringList: List[String] = List("a", "a", "b", "b", "c", "c")

val myFloatList: List[Float] = List(1f/2f, 1f/4f, 1f/8f)

val myMixedList: List[Matchable] = List(1, "2", 3.0)Output

myIntList: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

myStringList: List[String] = List(a, a, b, b, c, c)

myFloatList: List[Float] = List(0.5, 0.25, 0.125)

myMixedList: List[Matchable] = List(1, 2, 3.0)As we might have noticed, we had to declare the float list using at least one of the operands in each division: a Float or Double. This is because Scala handles integer division by discarding the remainder and keeping only the integer part of the result. In other words, if we’d like to perform a float division, we must provide at least one float (numerator or denominator).

Another interesting detail is that we use the Matchable type to be able to declare a list of mixed types. In general, it’s not a good practice to create lists with mixed types in Scala (or in most other statically-typed languages) because it reduces the type safety that Scala’s static typing provides. However, it’s possible to do, and the code executes without errors.

2. Array

An Array is a mutable, indexed collection of elements. Arrays are fixed-size, and their length is unchangeable. Unlike Lists, we can change the value of elements in an array after it’s been created.

One thing to note about arrays is that by default, they get printed using the toString representation, which is not very meaningful (it shows the type and hashcode of the array, like [I@77e8d3b1).

To print the contents of the array in a more readable way, we can use two different methods:

mkStringforeach

Code

// Declare array

val myArray: Array[Int] = Array(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

// Print string representation

print(myArray)

// Change array value using index (zero-based indexing)

myArray(0) = 0

// Print array elements using foreach

myArray.foreach(println)Output

// [I@3112137

// 0

// 2

// 3

// 4

// 53. Set

A Set is a collection of distinct elements. Elements in a set are not ordered. Scala provides both mutable and immutable Set.

Code

val mySet: Set[Int] = Set(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

println(mySet)Output

// HashSet(5, 1, 2, 3, 4)But wait a second…why is the Set printed in a different order than how it was originally declared? What happens is that, as mentioned, the Set collection in Scala does not maintain the order of elements. This is because Set is implemented as a HashSet by default, a data structure designed to optimize lookup times (checking if an element is contained in the set) rather than preserving insertion order.

In a HashSet, elements are organized based on their hash codes for quick lookup, which may not reflect the order in which they were added.

4. Map

A Map is a collection of key-value pairs. The keys in a map are unique. If we’ve worked with dictionaries in Python, this structure is what most resembles them:

Code

// Declare Map of Int -> String

val myMapInt: Map[Int, String] = Map(1 -> "one", 2 -> "two", 3 -> "three")

// Index Map by Int key

myMapInt(1)

// Declare Map of String -> Int

val myMapString: Map[String, Int] = Map("one" -> 1, "two" -> 2, "three" -> 3)

// Index Map by String key

myMapString("two")Output

res57: String = one

res58: Int = 2Keys can be of multiple types (Int, String); the only constraint is that they must be the same type and be unique values.

5. Tuple

A Tuple is an ordered group of elements. Unlike Lists and Arrays, Tuples are designed to hold elements of different types. They are immutable data structures useful when we want to return multiple values from a function.

We can declare tuples using three different ways:

Code

// Declare a tuple using a single type

val myTupleSingle: Tuple = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

// Declare a tuple using multiple but explicitly declared types

val myTupleMulti: (String, Int, String, String, Int) = ("1", 2, "3", "4", 5)

// Declare a tuple using multiple inferred types

val myTupleMulti_2 = (1, "2", 3, "4", "5", '6', 7)- In the first line, we declare a

Tuplecontaining one data type (Int), but without explicitly declaring the types. - In the second line, we declare a

Tuplecontaining multiple data types but explicitly declaring the types of each value. - In the last line, we declare a

Tuplecontaining multiple data types, but without explicitly declaring the types.

6. Option

An Option is a more advanced collection representing a value that may or may not exist. An Option can be either Some value or None.

Let us imagine we have a Map structure mapping names with ages and would like to retrieve a value given a key. In this case, a key might not exist in the Map declaration, so we can use an Option to ensure we don’t get errors when trying to index a non-existing key:

Code

val personAge = Map("John" -> 30, "Amy" -> 25)

def getAge(name: String): Option[Int] = {

personAge.get(name)

}

val johnAge = getAge("John")

val amyAge = getAge("Amy")

val unknownAge = getAge("Unknown")Output

johnAge: Option[Int] = Some(30)

amyAge: Option[Int] = Some(25)

unknownAge: Option[Int] = NoneWhat’s happening here is:

- We first declare a

Mapwith unique keys and values. - We then declare a function called

getAge, with the evaluation result asOption(it might or might not exist, it might or might not be anInt). - Next, we index using some existing and non-existing keys.

- In the first two cases, we get

Someas the output type, meaning it exists. - In the last case, we get

None, which means that no key was found; thus the correspondingAgeinteger value does not exist.

This is extremely useful because now, we can use pattern matching to make more sense of the data we’re getting:

Code

def checkAge(age: Option[Int]): Unit = age match

case Some(age) => println(s"The age is: ${age}")

case None => println(s"Sorry! Person does not exist.")

checkAge(johnAge)

checkAge(unknownAge)Output

// The age is: 30

// Sorry! Person does not exist.7. Vector

A Vector is a general-purpose, immutable data structure. It provides random access and updates in constant time, providing very fast append and prepend mechanisms.

Vectors support elements of the same type:

Code

val myVector: Vector[Int] = Vector(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)Higher-order functions

Higher-order functions are more of an advanced topic, but they’re worth mentioning since they’re a key aspect of Scala & functional programming in general.

Higher-order functions are functions that:

- Accept functions as parameters

- Can return functions as results

This is somewhat confusing, so let us explain it with a simple example:

Suppose we want to implement a method that sums all the items in a given list while performing some intermediate operation beforehand. This is called a variation of the summation operation and is very common in mathematics.

For the product variation, the mathematical expression would look something like such:

![]()

Normally, we would use one single function definition to approach this. However, one key aspect in functional programming is modularizing our functions, meaning one function ideally performs one single operation, and no more.

Thus, we can create two separate definitions that will complement each other:

Code

// Defining a list of values to operate on

val myTargetList: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

// Define the summation function

def sumList(l: List[Int], f: Int => Int): Int =

def sumNumbers(h: Int, t: List[Int], f: Int => Int): Int =

if (t.isEmpty) f(h)

else f(h) + sumNumbers(t.head, t.tail, f)

sumNumbers(l.head, l.tail, f)

def intSquared(x: Int): Int =

x*x

// Call function

sumList(myTargetList, intSquared)Let us break this step by step:

- We first declare a simple target