Programming paradigms play a crucial role in the realm of computer science. They act as blueprints or frameworks to organize code and tackle problems in a specific manner. Mastery of programming paradigms empowers us to select the most fitting approach for a given problem, considering its requirements, limitations, and inherent nature.

Furthermore, expanding our knowledge of different programming paradigms can widen our horizons and enable us to perceive problems and solutions from a fresh and innovative perspective. By comprehending various programming paradigms, we can gain access to novel techniques and tools that we can leverage to enhance our coding prowess and create software that is more streamlined, powerful, and resilient.

In this Blog Article, we’ll explain what they are, why they are essential, the primary paradigms and sub-paradigms, their defining traits, and their respective advantages and drawbacks. Using a real-life example, we will also illustrate the differences between the main paradigms. Finally, we will furnish a list of the most prominent programming languages along with their paradigmatic structure.

We’ll be using Python scripts which can be found in the Blog Article Repo.

What are programming paradigms?

A programming paradigm is a specific way of conceptualizing how to use a programming language to solve particular problems or build specific applications. It includes a set of guiding principles and best practices that should be followed to get the most out of the language.

Every programming language is designed to include one or more paradigms, while languages that can be used with more than one paradigm are referred to as multi-paradigm languages.

Moreover, programming languages can vary in how strictly they enforce programming style. Typically, multi-paradigm languages are more flexible and can be used by combining functionalities from different paradigms.

Why are they relevant?

Programming paradigms represent diverse strategies for approaching problem-solving. As we highlighted earlier, paradigms are akin to blueprints that shape our code. Consequently, learning about the primary classifications and their defining traits offers numerous advantages, including:

- Broadening our theoretical knowledge: Given its centrality to computer science, understanding programming paradigms provides valuable insights into the historical context of computer theory.

- Expanding our technical knowledge: Learning about paradigms also offers insight into how programming languages work since they are integrated into each language’s architecture.

- Promoting adaptability: Familiarity with existing paradigms makes it easier to shift to new ones.

- Encouraging intellectual growth: Delving into programming paradigms can challenge our thinking and broaden our problem-solving capabilities.

- Customizing our programming style: Grasping different paradigms allows us to design tailored solutions that align with our coding style. While we may loathe object-oriented programming, we might adore functional programming, which could motivate us to start coding in the first place.

- Promoting an appreciation for diversity: Learning diverse paradigms cultivates respect for the varied approaches taken by other programmers.

- Fueling creativity: Experimenting with multiple paradigms can inspire creativity and foster innovative ways of problem-solving.

- Promoting adaptability: Proficiency in multiple paradigms equips us with the versatility to adapt to evolving project requirements or technologies.

- Enhancing communication skills: Understanding diverse paradigms boosts our capacity to convey complex ideas to colleagues and stakeholders, including non-technical audiences.

- Developing intuition: Exploring different paradigms can help us hone our intuition for identifying the most appropriate approach to a particular problem based on what has worked before, what has not, and why.

The main paradigms

The two primary paradigms that give rise to other paradigms are:

- Imperative: As its name suggests, this paradigm centers on defining how a program should execute a task rather than what the task entails.

- Declarative: Unlike the imperative style, the declarative paradigm emphasizes describing the problem to be solved rather than specifying the steps required to solve it.

Let us now examine each of these paradigms in greater depth.

1. Imperative

The imperative style closely resembles the way machines operate and was officially introduced in the mid-1950s with the release of Fortran.

A classic imperative style explicitly defines a sequential set of commands the machine executes step-by-step. This approach focuses on the “how” to solve a problem, making it well-suited for low-level procedures; the hardware implementation of all computers is imperative in nature.

The imperative paradigm is further divided into two main subcategories that should be more familiar to us:

- Procedural

- Object-Oriented (OOP)

1.1 Procedural

The procedural style is founded on structured programming and comprises smaller units called procedures. Procedures define computational steps that need to be executed and can be called at any time during the execution.

Let us discuss some of the main characteristics of procedural programming:

- Predefined functions: These are typically named instructions built into higher-level programming languages. They are usually derived from the library or registry rather than the program. An example of a predefined function is

charAt(), which searches for a character position in a string. - Local variable: A local variable is declared within a method’s primary structure and is limited to the local scope in which it is defined. A local variable can only be used within the method in which it is defined, and if it were to be used outside the defined method, the code would cease to function.

- Global variable: A global variable is a variable that is declared outside every other function defined in the code. As a result, unlike local variables, global variables can be used in all functions.

- Modularity: Modularity involves grouping two different systems with distinct tasks to accomplish a larger task. Each group of systems completes its tasks one after the other until all tasks are completed.

- Parameter passing: Parameter passing is a mechanism used to pass parameters to functions, subroutines, or procedures. Parameter passing can be done through “pass by value,” “pass by reference,” “pass by result,” “pass by value-result,” and “pass by the name.”

Below is a list of the most relevant languages that use procedural style partially (multi-paradigm) or fully (100% procedural):

- C

- Pascal

- Fortran

- COBOL

- Ada

- ALGOL

- BASIC

- Assembly

1.2 Object Oriented

Object-Oriented programming is one of the most widely used paradigms due to its popularity in many high-level programming languages. The paradigm is based on the idea of objects that contain data in the form of fields, where a field represents a variable that is associated with a particular class or object. Fields are used to reflect the state of an object and can be accessed and modified by methods of the class or by external code that has access to the object.

Most OOP implementations use classes and inheritance, which provide extensibility, modularity, and reusability.

Let us discuss some of the main characteristics of OOP:

- Encapsulation: This principle dictates that an object should contain all the necessary information inside it and only expose a limited set of information. The object’s implementation and state are privately held inside a defined class, which other objects cannot access or modify. They can only access a list of public functions or methods. This property of data hiding provides greater security and helps prevent unintended data corruption.

- Abstraction: Objects only reveal internal mechanisms relevant to using other objects, hiding any unnecessary implementation code. This concept can help developers make additional changes or additions more easily over time.

- Inheritance: Classes can reuse code from other classes. Relationships and subclasses between objects can be assigned, enabling us to reuse common logic while maintaining a unique hierarchy.

- Polymorphism: Polymorphism allows different types of objects to pass through the same interface. Objects are designed to share behaviors and can take multiple forms. The program determines which meaning or usage is necessary for each execution of that object from a parent class, reducing the need to duplicate code. A child class is then created, extending the parent class’s functionality.

- Single Responsibility Principle: This principle states that each class or module should have only one responsibility. In other words, each class or module should be responsible for doing one thing and doing it well.

Below is a list of the most relevant languages that use OOP partially (multi-paradigm) or fully (100% OOP):

- Java

- Python

- Ruby

- C++

- PHP

- C#

- Swift

- Kotlin

- JavaScript

- TypeScript

- Golang

- Rust

- Scala

- Lua

1.3 Other paradigms

In addition to Procedural and Object-Oriented Programming, there are other less well-known styles in the Imperative Paradigm, including:

- Imperative Functional Programming: This style combines elements of imperative and functional programming, allowing side effects and mutable state while also supporting higher-order functions and other functional constructs. Imperative functional programming languages include Scala and F#.

- Imperative Dataflow Programming: This approach combines imperative programming with dataflow concepts. In this paradigm, programs are represented as graphs, and data is sent between nodes in the graph using message-passing. Imperative dataflow programming languages include Max and Pure Data.

2. Declarative

The declarative style has its roots in formal logic and mathematical notation, particularly the work of George Boole in the mid-19th century. The idea of describing a problem in terms of logical constraints and relations was further developed in the 20th century, leading to the creation of languages like Prolog in the 1970s.

Declarative programming emphasizes logic and concepts, focusing on the result we want to achieve rather than how to achieve it, in contrast to the “how” of the imperative style.

The declarative paradigm can be divided into three main subcategories, with the most popular being the functional paradigm:

- Logical

- Mathematical

- Functional

2.1 Logical

Logical programming is based on formal logic, a foundation of a significant part of mathematics and computer science. In a logical approach, there are no instructions, but rather, facts and clauses are introduced, relationships are created between them, and relationships are evaluated using pattern matching.

Queries related to the facts and clauses can then be made, and a boolean answer can be returned.

Let us discuss some of the main characteristics of logical programming:

- Declarative programming: Logic programming is a declarative programming paradigm that emphasizes describing what the program should do rather than how to do it.

- Logic facts and clauses: Programs in logic programming consist of a set of logical rules and facts used to derive new conclusions from existing knowledge.

- Backtracking: Logic programming often involves backtracking, where the program systematically explores different paths to find the most optimal solution.

- Unification: In logic programming, unification is used to match patterns in rules and facts and bind variables to values.

- Pattern matching: Logic programming languages often include powerful pattern-matching capabilities used to match and manipulate complex data structures.

- Non-determinism: Logic programming allows for non-determinism, meaning that there may be multiple possible solutions to a problem, and the program may explore multiple paths simultaneously.

Below is a list of the most relevant languages that use logical style partially (multi-paradigm) or fully (100% logical):

- Prolog

- Mercury

- Logtalk

- Gödel

2.2 Mathematical / academic

Mathematical programming is not formally considered a programming paradigm. However, multiple languages behave mathematically in nature. Most of the time, a mathematical language will have a functional component.

Let us discuss some of the main characteristics of mathematical programming:

- Symbolic expressions: Mathematical programming languages often use symbolic expressions, representing mathematical objects like equations and functions using symbolic notation.

- Mathematical operations: Mathematical programming languages include various mathematical operations and functions, such as trigonometric functions, linear algebra operations, and calculus functions.

- Numerical optimization: Mathematical programming often involves numerical optimization, where algorithms are used to find the optimal values of a set of parameters subject to constraints.

- Automatic differentiation: Some mathematical programming languages support automatic differentiation, a technique for efficiently computing the derivatives of functions.

- Statistics and data analysis: Mathematical programming languages often include support for statistical operations and data analysis, including probability distributions, hypothesis testing, and regression analysis.

Below is a list of the most relevant languages that use mathematical style partially (multi-paradigm) or fully (100% mathematical):

- MATLAB

- Mathematica (Wolfram Language)

- Maple

- Maxima

- SageMath

- R

- Julia

- Octave

2.3 Functional

The functional style is commonly acknowledged as the most widely adopted declarative paradigm. Its foundations are grounded in lambda calculus, and like logical and mathematical styles, it has a mathematical nature.

The construction of programs in functional programming is done through the definition and composition of functions. These functions accept input values, evaluate them, and produce output values, all while avoiding mutable state or side effects.

Let us discuss some of the main characteristics of functional programming:

- Pure functions: In functional programming, functions are generally pure, indicating that they do not generate side effects and always return the same output for the same input.

- First-class functions: Functional programming considers functions as first-class citizens, meaning they can be passed as arguments to other functions and returned as results from functions.

- Higher-order functions: The use of higher-order functions, such as map, filter, and reduce, is highly encouraged in functional programming. These are functions that operate on other functions.

- Immutable data: Functional programming highly favors immutable data structures that do not change in place but instead generate new data structures when changes are required. In fact, many of the purely functional languages enforce this rule.

- Recursion: Functional programming often employs recursive functions to process data structures recursively rather than using loops and mutable variables.

- Declarative programming: Functional programming often follows a declarative programming style in which programs describe what they do rather than how they do it.

- Lazy evaluation: Some functional programming languages use lazy evaluation, in which expressions are not evaluated until their values are necessary.

- Pattern matching: Many functional programming languages support pattern matching, an effective method of matching data structures against specific patterns and extracting values from them.

Below is a list of the most relevant languages that use functional style partially (multi-paradigm) or fully (100% functional):

- Haskell

- Common Lisp

- Clojure

- Erlang

- Elixir

- OCaml

- F#

- Scala

- Elm

- PureScript

- Racket

2.4 Other paradigms

While Procedural & OOP are the main imperative paradigms, there are lesser-known styles:

- Constraint logic programming: This paradigm merges the expressiveness of logic programming with the efficiency of constraint solving. In constraint logic programming, constraints are employed to describe relationships among variables and the language is used to determine values for these variables that fulfill the constraints. Mozart/Oz and ECLiPSe are examples of constraint logic programming languages.

- Dataflow programming: Dataflow programming views a program as a directed graph of the data that flows between operations. This approach emphasizes the movement and transformation of data through the graph. Lucid and LabVIEW are examples of dataflow programming languages.

- Query languages: These languages are designed for querying structured data, typically stored in databases or other data storage systems. They are declarative, describing what data should be retrieved but not how to retrieve it. SQL (Structured Query Language) is the most popular example of a query language used for relational databases, while SPARQL is used to query RDF (Resource Description Framework) data.

A practical example: The Clever Weather Wardrobe Oracle

Paradigms are sometimes hard to grasp if we’re thinking in abstract terms. Let us define an example to solidify our understanding:

We live in a world where, interestingly enough, our everyday clothing choices are exclusively selected by a fashion assistant called The Trendminator. This assistant exists to suggest the perfect outfit for every individual using a number of parameters such as current mood, weather, clothing preferences, and personality traits.

The creators of The Trendminator are thinking of multiple possible algorithmic implementations:

- A procedural approach

- An OOP approach

- A logical approach

- A mathematical approach

- A functional approach

The objective is to develop an algorithm that calculates the optimal outfit based on the user’s mood, current weather, clothing preferences, and personality.

1. A procedural approach

As we discussed, a procedural approach consists of a precise step-by-step execution while calling procedures at any given time in the code execution:

- We’ll start by gathering user input for mood, weather, clothing preferences, and personality traits.

- Next, we’ll use conditionals and loops to iterate through different clothing items and identify those that match the input criteria.

- We’ll then create separate functions for evaluating the suitability of each clothing item, like

is_appropriate_for_mood,is_appropriate_for_weather, andmatches_preferences. - Finally, we’ll use a function like

assemble_outfitto assemble a complete outfit from the selected clothing items.

Key takeaways:

- Procedural approaches are sometimes more extensive regarding code length since we need to declare every step of the program explicitly.

- Because of this, we usually have more control over our program.

- It also limits code reusability since functions are often tightly coupled to specific tasks or data structures.

- Additionally, procedural programming reduces flexibility and favors sequential execution (one step after another) over concurrency (alternating execution between two or more processes).

2. An OOP approach

With OOP, we can modularize code by creating classes and hierarchies:

- We’ll design a class hierarchy representing various clothing items, users, and the wardrobe wizard itself.

- We’ll create an abstract

ClothingItemclass with properties likename,type, andstyle, and methods likematches_mood,matches_weather, andmatches_preferences. - We’ll then, define subclasses for different clothing items, like

Shirt,Pants, andAccessories. - Next, we’ll define a

Userclass with properties for mood, weather, clothing preferences, and personality traits, and aWardrobeWizardclass that takes a user as input and has a methodsuggest_outfitwhich iterates through the available clothing items, checks their suitability using thematches_methods, and then assembles and returns the final outfit.

Key takeaways:

- OOP is easy to understand and explain to non-technical stakeholders.

- Inheritance can introduce tight coupling between classes, where changes to the parent class can have unintended consequences on the child class.

- Inheritance can also introduce inflexibility; it can be difficult to change the hierarchy of classes once established. This can make adapting to the evolving requirements or reusing code in different contexts difficult.

3. A logical approach

A logical approach would consist of defining facts and clauses specific to our Trendminator:

- We’ll first define facts and clauses about clothing items, user moods, weather conditions, clothing preferences, and personality traits.

- We’ll then deduce the ideal outfit for each user based on the given facts and rules. For example, we could establish facts like

fits_mood(clothing, mood),suitable_for_weather(clothing, weather), andpreferred_by_user(user, clothing), and then define rules to find the perfect outfit based on these facts.

Key takeaways:

- Logical approaches are perhaps more confusing than others since they require a good understanding of symbolic logic and constraint-solving techniques.

- They also introduce limited expressiveness, which can limit the capabilities of our application.

- Logical approaches can underperform in certain applications. This is because they rely heavily on backtracking and may need to explore many possible solutions before finding the correct one.

4. A mathematical approach

There are multiple ways we can use to approach a problem mathematically. In this case, we’re dealing with the best decision based on rules and constraints, so it would make sense to design our Trendminator’s brain around an optimization approach:

- We can formulate the problem as a mathematical optimization problem to maximize user satisfaction, subject to constraints such as mood, weather conditions, clothing preferences, and personality traits.

- We’ll start by defining variables for each clothing item and user preference and create a linear or integer programming model to represent the problem.

- We’ll then define our constraints to ensure that each clothing item is appropriate for the user’s mood, weather conditions, preferences, and personality traits and then create an objective function that maximizes user satisfaction.

- We’ll finally use a solver method to find the optimal solution.

Key takeaways:

- Mathematical approaches can work as black boxes with multiple levels of abstraction; we don’t need to implement the optimization method ourselves.

- Because of this, they can be trickier to implement and debug without the proper domain knowledge.

5. A functional approach

A functional approach ideally includes the use of higher-order functions, recursion, and pattern matching, to express Trendminator’s logic:

- We’ll start by defining data structures for clothing items, users, and their preferences.

- We’ll use higher-order functions like

filterto create lists of suitable clothing items based on the user’s mood, weather conditions, preferences, and personality traits. - We’ll then write a recursive function

assemble_outfitthat selects one item from each clothing category and combines them into a final outfit.

Key takeaways:

- Functional programming is sometimes simpler and more elegant.

- It makes use of functions instead of classes.

- It does not mutate parameters. Instead, it uses recursion to find the best possible solution.

- It can underperform in cases where low-level memory management is required and the language does not provide that kind of interaction.

Pros, cons, and use cases

Paradigms would not be useful to us if they did not present advantages & disadvantages between each other; each paradigm is tailored towards a specific set of applications, which, if used correctly, can relieve the problem-thinking and code-writing processes. These advantages & disadvantages are highly correlated with the nature of our application (i.e., what’s our code trying to achieve?)

For example, translating a research paper to a mathematical or purely functional language is straightforward, while the same might not be true for OOP or procedural.

More importantly, some applications simply cannot be implemented using specific paradigms in certain languages.

For example, we could never implement an ML model using SQL because the language was not designed to do so; it’s out of its capabilities and highly constrained by its architecture.

We can classify use cases using three particular situations:

- Situation 1: An application is entirely possible to deploy on a given language using a given paradigm:

- Situation 1.1: The translation / problem statement is easy to implement, and the code is performant.

- Situation 1.2: The translation / problem statement is easy to implement, but the code is underperforming.

- Situation 1.3: The translation / problem statement is hard to implement, but the code is performant.

- Situation 1.4: The translation / problem statement is hard to implement, and the code is underperforming.

- Situation 2: An application is not entirely possible to deploy on a given language using a given paradigm. We can encounter roadblocks that could result in low performance, an error-prone implementation, or even the application crashing altogether.

- Situation 3: An application is impossible to deploy on a given language using a given paradigm.

Of course, there’s a grayscale between these steps since writing code is never black & white, but the point is made.

Let us explore each situation in more detail.

Situation 1: Implementation is possible and ideal

This particular case can be rare; such a thing as a perfect implementation does not exist since all implementations have flaws. However, there are cases where the problem matches almost perfectly a given language and its associated paradigm(s).

A good example would be to model a family of 4 using OOP:

Code

class Family():

def __init__(self, family_name):

self.family_name = family_name

def getFamilyName(self):

return self.family_name

def introduceFamily(self):

print(f"Hi, we're the {self.family_name}'s.\n")

class Parent(Family):

def __init__(self, name, age, family_name):

super().__init__(family_name)

self.name = name

self.age = age

def getName(self):

return self.name

def introduceParent(self):

print(f"Hi, my name is {self.name} {self.getFamilyName()}. I'm {self.age} years old\n")

class Child(Parent):

def __init__(self, name, age, family_name, parent1, parent2):

super().__init__(name, age, family_name)

self.name = name

self.age = age

self.parents = [parent1, parent2]

def introduceChild(self):

print(f"Sup!, my name is {self.name} {self.family_name}. I'm {self.age} years old.")

print(f"My parents are {self.parents[0].getName()} and {self.parents[1].getName()}.\n")Now that we have our classes, we can start building some family members:

Code

# Create a family instance

family = Family("Johnson")

# Create 2 parents

parent_1 = Parent("Elena", "29", family.getFamilyName())

parent_2 = Parent("Paul", "32", family.getFamilyName())

# Create 2 children

child_1 = Child("Emma", "13", family.getFamilyName(), parent_1, parent_2)

child_2 = Child("Rowan", "12", family.getFamilyName(), parent_1, parent_2)We can then let them make some proper introductions:

Code

# Introduce family

family.introduceFamily()

# Introduce parents

parent_1.introduceParent()

parent_2.introduceParent()

# Introduce children

child_1.introduceChild()

child_2.introduceChild()Output

Hi, we're the Johnson's.

Hi, my name is Elena Johnson. I'm 29 years old

Hi, my name is Paul Johnson. I'm 32 years old

Sup!, my name is Emma Johnson. I'm 13 years old.

My parents are Elena and Paul.

Sup!, my name is Rowan Johnson. I'm 12 years old.

My parents are Elena and Paul.We can create as many subclasses and methods as we require (e.g., creating a Toddler class where the introduction method includes a Doodle Doo instead).

This implementation is possible and easy to execute since the concept of a family assimilates many of the core features of OOP:

- Abstraction: We can abstract a complex hierarchical structure and translate that into classes and subclasses.

- Inheritance: Children inherit some of their parent’s attributes, such as

family_name. - Single Responsibility: Each class has one function depending on the level of abstraction, and each method has one function (e.g.

introduce,get, etc.).

Another great example would be implementing a telecommunication system infrastructure using a concurrent language such as Erlang or Elixir; these languages were built for concurrency and fault tolerance in complex interconnected systems.

Situation 1.1: Translation is ideal, and the code is performant

What do we mean by translation? Let us think of an example where we have a classroom with 28 students and would like to abstract that concept and write an application that stores student grades.

There are a couple of ways to think of this problem abstraction-wise, but probably the most direct would be by using an OOP approach, where we define a class for the class, a subclass for the students, a subclass for assignments, and attributes for names & grades.

This translation is ideal since it perfectly matches the real-life situation (or at least the relevant aspects of it).

However, a smooth translation does not mean that code will be performant.

Situation 1.2: Translation is ideal, but the code is underperforming

There are situations where the abstraction is ideal, but the application’s performance is inefficient.

Let us look at an example where we want to implement a search algorithm and apply it to a list in Python:

Code

import time

# Implement a linear search algorithm

def linear_search(arr, target):

start_time = time.time()

for i in range(len(arr)):

if arr[i] == target:

end_time = time.time()

total_time = end_time - start_time

print(f'Linear Search: {round(total_time, 4)} s')

return i

return -1

# Implement a binary search algorithm

def binary_search(arr, target):

start_time = time.time()

start = 0

end = len(arr) - 1

while start <= end:

mid = (start + end) // 2

if arr[mid] == target:

end_time = time.time()

total_time = end_time - start_time

print(f'Binary Search: {total_time} s')

return mid

elif arr[mid] < target:

start = mid + 1

else:

end = mid - 1

return -1

# Declare a list and a target value

arr = [i for i in range(1000000000)]

target = 9999999

# Get results for both methods

linear_search(arr, target)

binary_search(arr, target)Output

Linear Search: 0.3736 s

Binary Search: 0.0 sAs we can see, the linear search algorithm takes more time to execute, while the binary search algorithm is much faster. This is due to the algorithm itself and is related to a concept called computational complexity.

Even though the first approach was easier to implement in terms of abstracting the problem, the performance was better for the binary_search implementation.

Situation 1.3: Translation is not ideal, but the code is performant

This situation is the inverse of the previous one: we have a problem abstraction harder to translate, but the results are performant compared to other implementations.

In this case, the binary_search algorithm would serve as a great example.

Situation 1.4: Translation is not ideal, and the code is underperforming

We always have situations where neither the abstraction process nor the performance is ideal. There are multiple reasons for this:

- Incorrect thinking of the problem-solving process.

- Using a non-ideal paradigm for the type of problem we’re trying to solve.

- Using an underperforming language.

- Using underperforming methods.

- Using underperforming data structures.

- Not adhering to a particular language’s best practices.

- Not adhering to programming general best practices.

- Writing crappy code altogether.

Situation 2: Implementation is possible but not ideal

We can have situations where an implementation is possible, but the problem abstraction, the paradigm, or the actual language used are not ideal for the solution; it is technically possible to write an operating system in Python, but it would not be practical nor efficient.

This happens more often than not simply because finding the perfect match is hard. However, we currently have a variety of languages to choose from; the only limitation is actually knowing about them and being critical when evaluating a potential solution to the problem.

Situation 3: Implementation is impossible

There are situations where a given implementation is simply not possible. This can be due to multiple reasons:

- The paradigm is not suited for the required task.

- The language does not support the intended methods.

- There is not enough low-level control.

- The resource allocation mechanisms in a given language are insufficient for a given application.

Use cases

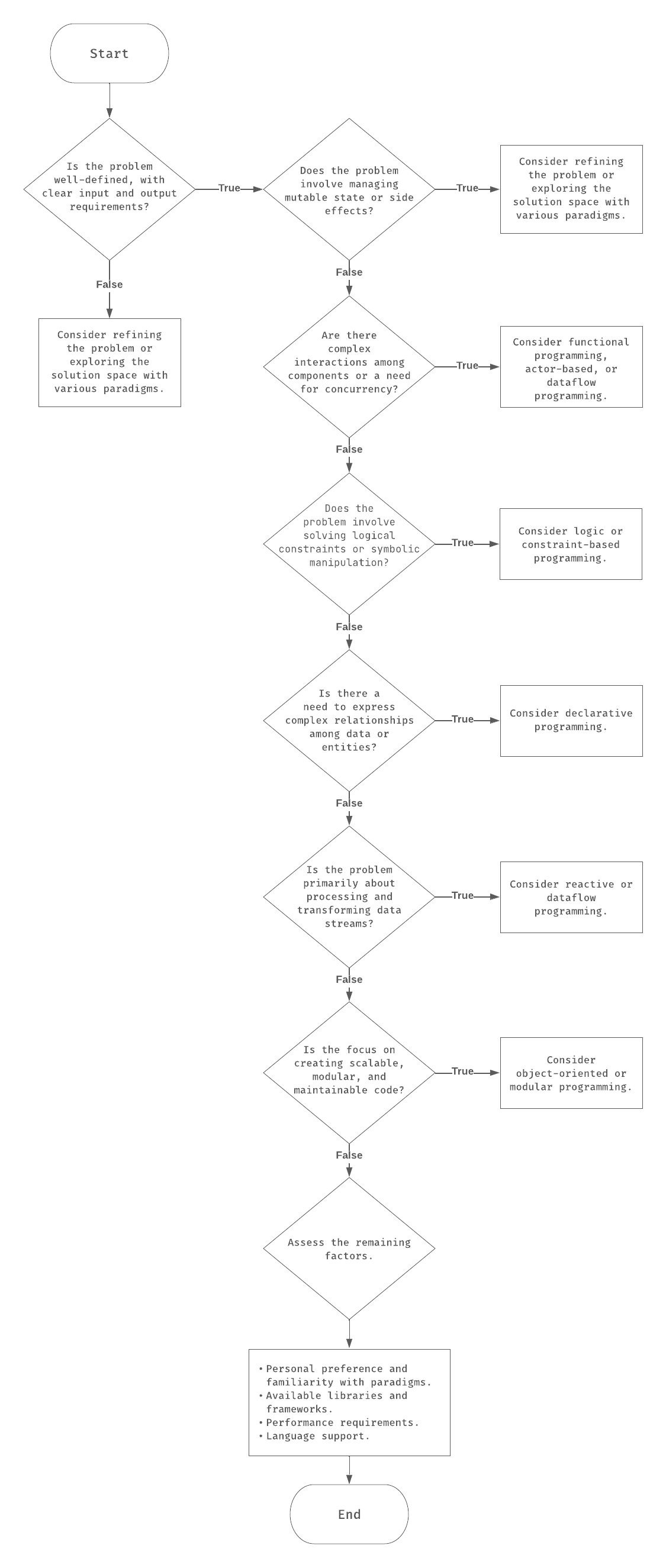

As mentioned, selecting the right workhorse is vital when designing a new application. Although no handbook correctly maps every possible application to a corresponding paradigm, there are guidelines we can follow to make our life easier:

Composition of popular languages

We mentioned that languages can adopt a paradigm as 100% of their structure or include multiple paradigms; it all depends on the problem we’re trying to solve.

Most of the popular languages are comprised of at least two paradigms having one predominant one. Below is a table of the most popular languages with their approximate paradigm composition:

| Language | Main Paradigm | Paradigms | Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ada | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, procedural | OOP: 60%, Procedural: 40% |

| Agda | Functional | Functional, dependent types | Functional: 90%, Dependent types: 10% |

| Assembly | Imperative | Imperative | Imperative: 100% |

| Bash | Procedural | Procedural, functional | Procedural: 70%, Functional: 30% |

| C | Procedural | Procedural | Procedural: 100% |

| C# | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, generic | OOP: 70%, Functional: 15%, Procedural: 10%, Generic: 5% |

| C++ | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Procedural) | Object-oriented, procedural, generic, functional | OOP: 50%, Procedural: 30%, Generic: 15%, Functional: 5% |

| Clojure | Functional | Functional, concurrent, homoiconic, Lisp dialect | Functional: 70%, Concurrent: 20%, Homoiconic: 5%, Lisp dialect: 5% |

| COBOL | Procedural | Procedural, imperative | Procedural: 80%, Imperative: 20% |

| Common Lisp | Multi-paradigm (Functional & OOP) | Functional, object-oriented, procedural, metaprogramming, Lisp dialect | Functional: 40%, OOP: 40%, Procedural: 10%, Metaprogramming: 5%, Lisp dialect: 5% |

| Crystal | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, procedural, functional | OOP: 60%, Procedural: 25%, Functional: 15% |

| Dart | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, generic | OOP: 60%, Functional: 20%, Procedural: 15%, Generic: 5% |

| DAX | Data-driven | Data-driven, functional | Data-driven: 80%, Functional: 20% |

| Elixir | Functional | Functional, concurrent, process-oriented | Functional: 60%, Concurrent: 30%, Process-oriented: 10% |

| Elm | Functional | Functional, reactive, static typing | Functional: 80%, Reactive: 15%, Static typing: 5% |

| Erlang | Functional | Functional, concurrent, process-oriented | Functional: 60%, Concurrent: 30%, Process-oriented: 10% |

| F# | Functional | Functional, object-oriented, procedural, generic | Functional: 60%, OOP: 25%, Procedural: 10%, Generic: 5% |

| Fortran | Imperative | Imperative, procedural | Imperative: 70%, Procedural: 30% |

| Go | Procedural | Procedural, concurrent, functional | Procedural: 70%, Concurrent: 20%, Functional: 10% |

| Groovy | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Functional) | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, metaprogramming | OOP: 50%, Functional: 30%, Procedural: 15%, Metaprogramming: 5% |

| Haskell | Functional | Functional, lazy evaluation, type-driven | Functional: 80%, Lazy evaluation: 15%, Type-driven: 5% |

| HTML/CSS | Markup/Stylesheet | Markup, stylesheet | Markup: 50%, Stylesheet: 50% |

| Idris | Functional | Functional, dependent types | Functional: 90%, Dependent types: 10% |

| Java | Object-oriented | Object-oriented | OOP: 100% |

| JavaScript | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Functional) | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, event-driven | OOP: 40%, Functional: 40%, Procedural: 15%, Event-driven: 5% |

| Julia | Multi-paradigm (Procedural & Functional) | Procedural, functional, object-oriented, metaprogramming | Procedural: 40%, Functional: 40%, OOP: 15%, Metaprogramming: 5% |

| Kotlin | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Functional) | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, generic | OOP: 50%, Functional: 40%, Procedural: 5%, Generic: 5% |

| Lisp | Multi-paradigm (Functional & Procedural) | Functional, procedural, object-oriented | Functional: 50%, Procedural: 40%, OOP: 10% |

| Lua | Multi-paradigm (Procedural & Functional) | Procedural, functional, object-oriented, data-driven | Procedural: 50%, Functional: 30%, OOP: 15%, Data-driven: 5% |

| MATLAB | Multi-paradigm (Procedural & Functional) | Procedural, functional, array | Procedural: 60%, Functional: 30%, Array: 10% |

| OCaml | Multi-paradigm (Functional & OOP) | Functional, object-oriented, procedural, generic | Functional: 50%, OOP: 30%, Procedural: 15%, Generic: 5% |

| Perl | Multi-paradigm (Procedural & Functional) | Procedural, functional, object-oriented | Procedural: 50%, Functional: 40%, OOP: 10% |

| PHP | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Procedural) | Object-oriented, procedural, functional | OOP: 50%, Procedural: 40%, Functional: 10% |

| PowerShell 7 | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, procedural, functional, pipeline-based | OOP: 50%, Procedural: 25%, Functional: 20%, Pipeline-based: 5% |

| Prolog | Logic | Logic, declarative | Logic: 70%, Declarative: 30% |

| PureScript | Functional | Functional, strong static typing | Functional: 90%, Strong static typing: 10% |

| Python | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Procedural) | Object-oriented, procedural, functional | OOP: 60%, Procedural: 30%, Functional: 10% |

| R | Multi-paradigm (Functional & Procedural) | Functional, procedural, object-oriented | Functional: 60%, Procedural: 30%, OOP: 10% |

| Racket | Multi-paradigm (Functional & OOP) | Functional, object-oriented, metaprogramming, Lisp dialect | Functional: 50%, OOP: 30%, Metaprogramming: 15%, Lisp dialect: 5% |

| Ruby | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, functional, procedural | OOP: 80%, Functional: 10%, Procedural: 10% |

| Rust | Multi-paradigm (Procedural & Functional) | Procedural, functional, concurrent, generic | Procedural: 50%, Functional: 30%, Concurrent: 10%, Generic: 10% |

| Scala | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Functional) | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, concurrent | OOP: 40%, Functional: 40%, Procedural: 10%, Concurrent: 10% |

| Smalltalk | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, message-passing | OOP: 90%, Message-passing: 10% |

| SQL | Declarative | Declarative, data manipulation, data definition | Declarative: 100% |

| Swift | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Functional) | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, generic | OOP: 50%, Functional: 40%, Procedural: 5%, Generic: 5% |

| TypeScript | Multi-paradigm (OOP & Functional) | Object-oriented, functional, procedural, event-driven | OOP: 40%, Functional: 40%, Procedural: 15%, Event-driven: 5% |

| Visual Basic | Object-oriented | Object-oriented, procedural | OOP: 70%, Procedural: 30% |

Conclusions

Throughout this article, we explored the primary programming paradigms and sub-paradigms, examining their defining characteristics and pros and cons. We also highlighted the differences between the main paradigms using a practical example, demonstrating each paradigm’s unique advantages in particular scenarios.

Moreover, we presented a comprehensive list of popular programming languages along with their paradigmatic affiliations. This knowledge can guide us in choosing the right language for our projects and encourage us to investigate new languages and paradigms, expanding our skill set and fostering innovation.

Programming paradigms are invaluable tools in computer science, providing frameworks and methodologies for effectively tackling various problems. Understanding and mastering these paradigms allows us to select the most appropriate approach for specific challenges, leading to more efficient and robust software solutions.