In the last part of this 3-segment Guided Project, we introduced the concept of Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA). We made some initial data exploration and chose a set of risk factors which could be potentially used to predict the severity of a given patient’s Lung Cancer condition. We also introduced a simple business case requested by our client, an insurance company, and proceeded to analyze a data set provided.

In this section, we will go over 12 different classification algorithms. We will start by preparing our data. We will then discuss, in a very general way, the underlying theory behind each model and its assumptions. We will finally implement each method step-by-step and make a performance comparison.

We’ll use Python scripts found in the Guided Project Repo.

The generated plots and test results from the last segment can also be found in the plots and outputs folder respectively.

Classification model implementation

Classification models are a subset of supervised machine learning algorithms. A typical classification model reads an input and tries to classify it based on some predefined properties. A straightforward example would be the classification of a mail containing spam vs one without spam.

The other type of supervised algorithm, perhaps more familiar, is regression models. These differ because they don’t classify our inputs but predict continuous variables. A typical example would be predicting the stock market behaviour for a given asset.

1. Selecting our methods

We can implement multiple supervised models to try to predict the severity of Lung Cancer for a given patient. It’s always a good idea to test at least a set of different models and compare their accuracy. Since we have categorical, ordinal variables, we will test different classification algorithms.

It’s also important to consider that not every classification algorithm is appropriate for every classification problem. Each model is based on assumptions that may render it unusable for certain applications.

In this example, we will be working with 12 classification models, which we’ll explain in more detail further on:

- Multinomial Logistic Regression

- Decision Tree

- Random Forest

- Support Vector Machine

- K-Nearest Neighbors

- K-Means Clustering

- Gaussian Naïve Bayes

- Bernoulli Naïve Bayes

- Stochastic Gradient Descent

- Gradient Boosting

- Extreme Gradient Boosting

- Deep Neural Networks

2. Creating a Virtual Environment

Before anything else, we need to check our current Python version. This is important because although we’ll not be using tensorflow directly, we will require it for our Deep Neural Network model using keras, and tensorflow currently supports *Python versions 3.7 – 3.10:

Code

import sys

sys.versionOutput

'3.11.1 (tags/v3.11.1:a7a450f, Dec 6 2022, 19:58:39) [MSC v.1934 64 bit (AMD64)]'We can consult each operating system’s tensorflow installation requirements here.

If we have a Python version within the range above, we’ll be fine and can skip to the module installation part. Otherwise, we have two options:

- Install an older version of Python user-wide or system-wide, and use it as our default interpreter.

- Create a new virtual environment containing a downgraded Python version.

The second option is always best practice because another program we wrote might be using a newer Python version. If we replace our current Python version with an older one, we could break any program we wrote using more recent versions. Virtual environments handle these types of conflicts; we can have multiple Python installations and selectively choose which environment to work with, depending on each case.

Since we require a different Python version than the one we have, we will first download and install our target version by heading to the Python Releases for Windows site.

We will then select the version that we want to download. For this case, we will use Python 3.10.0 – Oct. 4, 2021 by getting the corresponding 64-bit Windows installer. Upon download, we will execute the installer and wait for it to conclude. A new Python version will be installed on our system.

Since we installed it user-wide, the executable will be found on C:/Users/our_username/AppData/Local/Programs/Python. We must remember this path since we will use it to point to the Python version upon our venv creation.

We will then create a new virtual environment dedicated to this project. For this, we will need to first cd into our project directory:

Code

cd 'C:/Users/our_username/exploratory-data-analysis'We will then create the environment using the built-in venv package. We can provide whichever name we like. Since we don’t have Python 3.10 specified in PATH, we will need to refer to it by specifying the full absolute path.

Code

C:\Users\our_username\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python310\python.exe -m venv 'eda_venv'We will see that a new folder was created on our working directory:

lsOutput

eda_venv

outputs

plots

cancer patient data sets.csv

exploratory-data-analysis-1.py

exploratory-data-analysis-2.pyWe can then activate our environment:

Code

cd eda_venv\Scripts

.\Activate.ps1We must remember that this Activate.ps1 is intended to be run by Microsoft PowerShell. We must check which activate version to use if we’re running a different shell. The activate.bat file should be executed for cmd.

We are now inside our virtual environment using Python 3.10. To confirm, we can look at the left of our command prompt, which should display eda_venv.

In order to start using the new environment in our IDE, there’s one additional step we must perform; this heavily depends on which IDE we’re using, but typically we’ll have to point it to our new interpreter (eda_venv/Scripts/python.exe) by specifying its path on our preferences menu.

- On Spyder:

- We can head to Tools, Preferences, Python Interpreter.

- We can then input the interpreter’s path.

- On VS Code:

- We can open the command palette by pressing F1.

- We can then search for Python: Select Interpreter.

- We can input our interpreter’s path.

We can manage the required dependencies for our project by using arequirements.txt file. If we’re using a version control system such as GitHub, the best practice is to add our eda_venv folder to our .gitignore file. For this, we will create a new requirements.txt file and place it in our folder project:

Code

cd exporatory-data-analysis

New-Item requirements.txtWe will then include the following and save it:

Code

matplotlib

seaborn

numpy

pandas

scipy

scikit-learn

keras

xgboost

tensorflow==2.10

xlsxwriter

visualkeras

pydot

pydotplusIf we’re using a Windows machine, we can install tensorflow r2.10 since this was the last release to support GPU processing on native Windows. We can also stick with the tensorflow-cpu package since our data set is not extensive, but tensorflow leverages GPU processing power to perform faster, especially in deep learning models. We will use the GPU-powered tensorflow package for this segment, hence the version definition on our requirements.txt file.

We will also need to install the NVIDIA CUDA Toolkit & the CUDA Deep Neural Network (cuDNN) library if we wish to enable GPU processing. We can head to the CUDA Toolkit Downloads page and get the version for our case (it’s important to read all CUDA requirements, i.e. Visual Studio is required for it to work properly. Also, tensorflow requires a specific CUDA version). For cuDNN, we can head to the NVIDIA cuDNN page (we will have to create an NVIDIA developer account for this one).

3. Preparing our environment

Now that we have our environment ready, we can install all our packages using the requirements.txt file we just generated:

Code

cd exploratory-data-analysis

pip install -r requirements.txtAnd that’s it; we have every package we need on our virtual environment and ready to be imported.

We can then import the required modules:

Code

# Data manipulation modules

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import xlsxwriter

import re

# Plotting modules

import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sn

from sklearn import tree

import visualkeras

from PIL import ImageFont

# Preprocessing modules

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder, StandardScaler, FunctionTransformer

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, KFold

# Evaluation & performance modules

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, classification_report

# Machine Learning models

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.naive_bayes import GaussianNB, BernoulliNB

from sklearn.linear_model import SGDClassifier

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingClassifier

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.layers import Dense, Dropout, Activation

# Utility modules

import warnings

import shutilWe can suppress unnecessary warnings and define plot parameters:

Code

# Supress verbose warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

# Define plot parameters

# Before anything else, delete the Matplotlib

# font cache directory if it exists, to ensure

# custom font propper loading

try:

shutil.rmtree(matplotlib.get_cachedir())

except FileNotFoundError:

pass

# Define main color as hex

color_main = '#1a1a1a'

# Define title & label padding

text_padding = 18

# Define font sizes

title_font_size = 17

label_font_size = 14

# Define rc params

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = [14.0, 7.0]

plt.rcParams['figure.dpi'] = 300

plt.rcParams['grid.color'] = 'k'

plt.rcParams['grid.linestyle'] = ':'

plt.rcParams['grid.linewidth'] = 0.5

plt.rcParams['font.family'] = 'sans-serif'

plt.rcParams['font.sans-serif'] = ['Lora']As we have multiple models, it will be best to build a dictionary with each name as Key and each model as Value. We will also define our model parameters inside each model so we don’t have to define them as additional variables in our workspace:

Code

# Define model dictionary

model_dictionary = {

'Multinomial Logistic Regressor': LogisticRegression(multi_class='multinomial',

solver='lbfgs',

random_state=42,

max_iter=100000,

penalty='l2',

C=24),

'Logistic Regressor' : LogisticRegression(C=24),

'Decision Tree Classifier': DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=9),

'Random Forest Classifier': RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators = 100),

'Support Vector Classifier': SVC(C=0.12, gamma=0.02, kernel='linear'),

'Support Vector Classifier Polynomial Kernel': SVC(C=1, gamma=0.6, kernel='poly', degree=8),

'Support Vector Classifier Radial Kernel': SVC(C=1, gamma=0.6, kernel='rbf'),

'K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier' : KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=5),

'Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier': GaussianNB(),

'Bernoulli Naive Bayes Classifier': BernoulliNB(),

'Stochastic Gradient Descent': SGDClassifier(loss='log',

max_iter=10000,

random_state=42,

penalty='l2'),

'Gradient Boosting Classifier': GradientBoostingClassifier(),

'Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier' : XGBClassifier(),

'Sequential Deep Neural Network' : Sequential()

}We can then define a dictionary which will contain all the preprocessing functions that we will need:

Code

preprocessing_dictionary = {'Right Skew Gaussian' : FunctionTransformer(func = np.square),

'Left Skew Gaussian' : FunctionTransformer(func = np.log1p),

'Standard Scaler' : StandardScaler()

}We can then import our data set and do some preprocessing:

Code

# Read the data set

df = pd.read_csv('cancer patient data sets.csv')

# Remove index column

df.drop(columns = "index", inplace = True)

# Map Level to numeric values

illness_level_dict = {'Low' : 1,

'Medium' : 2,

'High': 3}

df['Level'] = df['Level'].map(illness_level_dict)

# Remove columns that we will not study

remove_cols = ['Patient Id',

'Gender',

'Age',

'Chest Pain',

'Coughing of Blood',

'Fatigue',

'Weight Loss',

'Shortness of Breath',

'Wheezing',

'Swallowing Difficulty',

'Clubbing of Finger Nails',

'Frequent Cold',

'Dry Cough',

'Snoring']

df = df.drop(columns = remove_cols)

print(df.shape)

print(list(df.columns))We end up with a DataFrame with the following characteristics:

Output

(1000, 26)

['Air Pollution', 'Alcohol use', 'Dust Allergy', 'OccuPational Hazards', 'Genetic Risk', 'chronic Lung Disease', 'Balanced Diet', 'Obesity', 'Smoking', 'Passive Smoker', 'Level']If we recall from the last section, these are the potential risk factors that our client is looking to study. We had to remove all the other symptomatic characteristics as our client is not interested in these.

We will now define a simple function that will help us split our data into train and test sets:

Code

def sep(dataframe):

'''

Parameters

----------

dataframe : DataFrame

Contains our data as a DataFrame object.

Returns

-------

x : DataFrame

Contains our features.

y : DataFrame

Contains our labels.

'''

target = ["Level"]

x = dataframe.drop(target , axis = 1)

y = dataframe[target]

return x, yWe will now define three functions that will help us with the results generation:

cm_plotwill plot a confusion matrix for each method. Confusion matrices are a special kind of contingency table with two dimensions (actual and predicted). The idea behind the confusion matrix is to get a quick graphical grasp of how our model performed in predicting compared to the test data. It is a widely used and straightforward method to implement and explain to a non-technical audience.model_scorewill calculate the model score as the coefficient.

coefficient.classification_repwill calculate ,

,  ,

,  and

and  for each label and return it as a DataFrame object.

for each label and return it as a DataFrame object.

Code

# Define Confusion Matrix Function

def cm_plot(model_name, model, test_y, predicted_y):

'''

Parameters

----------

model_name : Str

Contains the used model name.

model : sklearn or keras model object

Contains a model object depending on the model used.

test_y : DataFrame

Contains the non-scaled test values for our data set.

predicted_y : Array

Contains the predicted values for a given method.

Returns

-------

None.

'''

cm = confusion_matrix(test_y, predicted_y)

plt.figure(f'{model_name}_confusion_matrix')

sn.heatmap(cm, annot=True, linewidth=0.7, cmap="rocket")

plt.title(f'{model_name} Confusion Matrix\n')

plt.xlabel('y Predicted')

plt.ylabel('y Test')

plt.savefig('plots/' + f'{model_name}_confusion_matrix_tp.png', format = 'png', dpi = 300, transparent = True)

plt.close()

return None

# Define model score

def model_score(model, test_x, test_y):

'''

Parameters

----------

model : sklearn or keras model object

Contains a model object depending on the model used.

test_x : Array

Contains the transformed / scaled test values for the features.

test_y : DataFrame

Contains the un-scaled / un-transformed test values for the labels.

Returns

-------

sc : Float

Contains the score model.

'''

sc = model.score(test_x, test_y)

return sc

# Define Classification Report Function

def classification_rep(test_y, predicted_y):

'''

Parameters

----------

test_y : DataFrame

Contains the non-scaled test values for our data set.

predicted_y : Array

Contains the predicted values for a given method.

Returns

-------

cr : DataFrame

Contains a report showing the main classification metrics.

'''

cr = classification_report(test_y, predicted_y, output_dict=True)

cr = pd.DataFrame(cr).transpose()

return crWe will now transform our data in order to make it usable for each model:

Code

# For Normal Distribution Methods, we can approximate our data set to

# a normal distribution

right_skew = []

left_skew = []

for i in df_x.columns:

if df_x[i].skew() > 0:

right_skew.append(i)

else:

left_skew.append(i)

right_skew_transformed = preprocessing_dictionary['Right Skew Gaussian'].fit_transform(df_x[right_skew])

left_skew_transformed = preprocessing_dictionary['Left Skew Gaussian'].fit_transform(df_x[left_skew])

df_gaussian = pd.concat([right_skew_transformed,

left_skew_transformed ,

df_y] ,

axis = 1,

join = "inner")

# We can divide into train & text, x & y

train_G, test_G = train_test_split(df_gaussian, test_size=0.2)

train_Gx, train_Gy = sep(train_G)

test_Gx, test_Gy = sep(test_G)

# For other methods, we can scale using Standard Scaler

train, test = train_test_split(df, test_size=0.2)

train_x, train_Sy = sep(train)

test_x, test_Sy = sep(test)

train_Sx = preprocessing_dictionary['Standard Scaler'].fit_transform(train_x)

test_Sx = preprocessing_dictionary['Standard Scaler'].transform(test_x)Now that we have our transformed sets, we can start talking about the selected models. For each case, we will briefly describe what the model is about, its general mathematical intuition, and its assumptions.

The mathematical background provided in this segment is, by any means, a rigorous derivation. We could spend an entire series talking about one model’s mathematical background. Instead, we will review the main mathematical formulae involved in each model.

4. A word on model assumptions

Assumptions denote the collection of explicitly stated (or implicit premised) conventions, choices and other specifications on which any model is based.

Every model is built on top of assumptions. They provide the theoretical foundation for it to exist and be valid, and machine learning models are no exception. That is not to say that every assumption must be rigorously met for a given model to work as expected, but we cannot bypass every assumption and expect our model to work as designed.

If we understand the underlying theory behind our model, we can be selective in the assumptions we can live without; we can gain knowledge on the implications of bypassing a particular assumption and thus make a supported decision on which model to use. It’s a matter of balance and finding out what’s suitable for our case.

5. Multinomial Logistic Regression

Multinomial Logistic Regression is a classification method that generalizes logistic regression to multiclass problems, i.e. when we have more than two possible discrete outcomes.

Logistic Regression, or Logit Model, contrary to what its name may suggest, is not a regression model but a parametric classification one. In reality, this model is very similar to Linear Regression; the main difference between the two is that in Logistic Regression, we don’t fit a straight line to our data. Instead, we fit an ![]() shaped curve, called Sigmoid, to our observations.

shaped curve, called Sigmoid, to our observations.

5.1 Mathematical intuition overview

Logistic Regression fits data to a ![]() function:

function:

![]()

It first calculates a weighted sum of inputs:

![]()

It then calculates the probability of the weighted feature belonging to a given group:

![]()

Weights are calculated using different optimization models, such as Gradient Descent or Maximum Likelihood.

Multinomial Logistic Regression uses a linear predictor function ![]() to predict the probability that observation

to predict the probability that observation ![]() has outcome

has outcome ![]() , of the following form:

, of the following form:

![]()

Where:

is the set of regression coefficients.

is the set of regression coefficients. is the outcome.

is the outcome. is a row vector containing the set of explanatory variables associated with observation

is a row vector containing the set of explanatory variables associated with observation  .

.

We can express our predictor function in a more compact form, since the regression coefficients and explanatory variables are normally grouped into vectors of size ![]() :

:

![]()

When fitting a multinomial logistic regression model, we have several outcomes (![]() ), meaning we can think of the problem as fitting

), meaning we can think of the problem as fitting ![]() independent Binary Logit Models. From the Binary Logit Model equation, we can express our predictor functions as follows:

independent Binary Logit Models. From the Binary Logit Model equation, we can express our predictor functions as follows:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

We can then exponentiate both sides of our equation to get probabilities:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

5.2 Assumptions

- It requires the dependent variable to be binary, multinomial or ordinal.

- It has a linear decision surface, meaning it can’t solve non-linear problems.

- Requires very little to no multicollinearity, meaning our independent variables must not be correlated with each other.

- Usually works best with large data sets and requires sufficient training examples for all the categories to make correct predictions.

5.3 Implementation

We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Multinomial Logistic Regressor'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_MLogReg = model_dictionary['Multinomial Logistic Regressor'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Multinomial Logistic Regressor',

model_dictionary['Multinomial Logistic Regressor'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_MLogReg)

# Define model score

score_MLogReg = model_score(model_dictionary['Multinomial Logistic Regressor'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_MLogReg = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_MLogReg)

print(score_MLogReg)Output

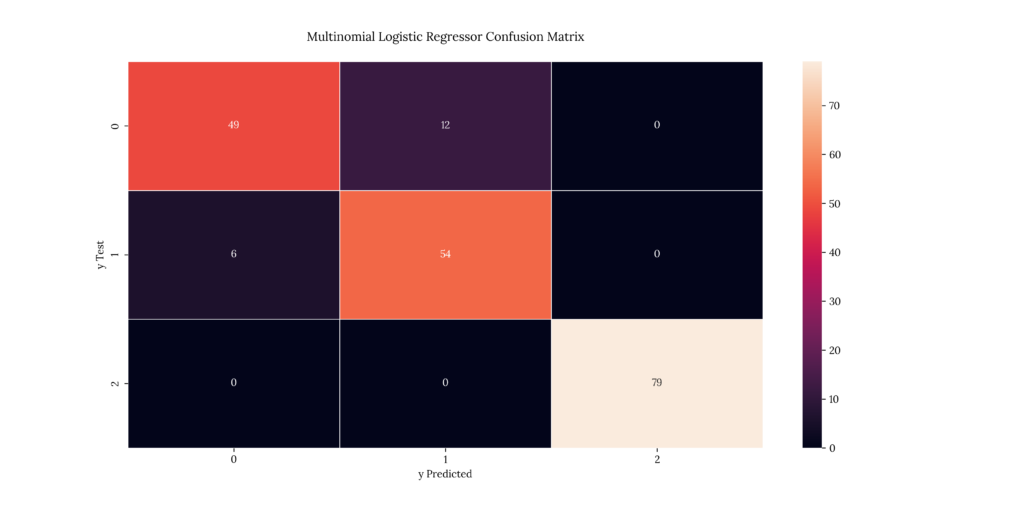

As we discussed earlier, a confusion matrix tells us the number of predicted values for each severity level vs the test values we’re comparing results with. The matrix diagonal denotes the predicted & test value match.

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.890909 | 0.803279 | 0.844828 | 61 |

| 2 | 0.818182 | 0.9 | 0.857143 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| macro avg | 0.90303 | 0.901093 | 0.900657 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 0.912182 | 0.91 | 0.909815 | 200 |

A classification report has 7 different metrics:

The precision is the number of true positive results divided by the number of all positive results, including those not identified correctly:

![]()

Where:

are the true positives.

are the true positives. are the false positives.

are the false positives.

The recall is the number of true positive results divided by the number of all samples that should have been identified as positive:

![]()

Where:

are the true positives.

are the true positives. are the false positives.

are the false positives.

The f1-score is the harmonic mean of the precision and recall. The highest possible value of an F-score is 1.0, indicating perfect precision and recall, and the lowest possible value is 0 if either precision or recall is zero:

![]()

The accuracy is the sum of true positives and true negatives divided by the total number of samples. This is only accurate if the model is balanced. It will give inaccurate results if there is a class imbalance:

![]()

Where:

are the true positives.

are the true positives. are the true negatives.

are the true negatives. are the false positives.

are the false positives. are the false negatives.

are the false negatives.

In our case, we have a balanced class. We can confirm this fact:

Code

df.groupby('Level')['Level'].count() / len(df) * 100Output

Level

1 30.3

2 33.2

3 36.5

Name: Level, dtype: float64We can see that we have roughly the same percentage of patients distributed along Lung Cancer severity levels, so for our case, the accuracy metric will be the most helpful way to evaluate our models.

If we had an unbalanced label class, we would have to perform special treatments to implement our models, and we would not be able to use accuracy as our model evaluator.

The macro-averaged f1-score is computed using the arithmetic or unweighted mean of all the per-class f1 scores.

The weighted average of precision, recall and f1-score takes the weights as the support values.

If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 91.5% accuracy:

Output

0.915Not to worry, we will explore the results in more detail in the Method Comparison section.

We can now use a Binomial Logistic Regression model and see what we get:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Logistic Regressor'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)

# Predict

y_predicted_BLogReg = model_dictionary['Logistic Regressor'].predict(test_Sx)

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Logistic Regressor',

model_dictionary['Logistic Regressor'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_BLogReg)

# Define model score

score_BLogReg = model_score(model_dictionary['Logistic Regressor'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_BLogReg = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_BLogReg)

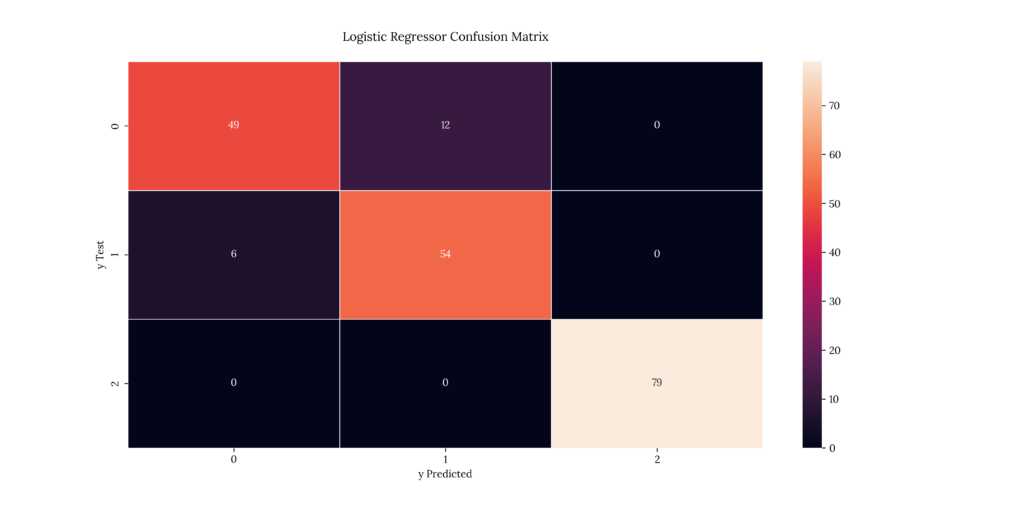

print(score_BLogReg)If we look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 91.5% accuracy. Same as its multinomial cousin:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.890909 | 0.803279 | 0.844828 | 61 |

| 2 | 0.818182 | 0.9 | 0.857143 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| macro avg | 0.90303 | 0.901093 | 0.900657 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 0.912182 | 0.91 | 0.909815 | 200 |

Output

0.9156. Decision Tree

A Decision Tree is a technique that can be used for classification and regression problems. In our case, we’ll be using a Decision Tree Classifier.

A Decision Tree has two types of nodes:

- Decision Node: These are in charge of making decisions and branch in multiple nodes.

- Leaf Node: These are the outputs of the decision nodes and do not branch further.

A Decision Tree algorithm starts from the tree’s root node containing the entire data set. It then divides the root node into subsets containing possible values for the best attributes. It then compares values of the best attribute using Attribute Selection Measures (ASM). It then generates a new node, which includes the best attribute. Finally, it recursively makes new decision trees using the subsets of the dataset and continues until a stage is reached where it cannot further classify the nodes. This is where the final node (leaf node) is created.

6.1 Mathematical intuition overview

Attribute Selection Measures (ASM) determine which attribute to select as a decision node and branch further. There are two main ASMs:

6.1.1 Information Gain

Measures the change in entropy after the segmentation of a dataset based on an attribute occurs:

![]()

We can interpret entropy as impurity in a given attribute:

![]()

Where:

is the data set

is the data set  .

. is the dataset

is the dataset  .

. represents the proportion of the values in

represents the proportion of the values in  to the number of values in dataset,

to the number of values in dataset,  .

. is the probability of class

is the probability of class  in a node.

in a node.

The more entropy removed, the greater the information gain. The higher the information gain, the better the split.

6.1.2 Gini Index

Measures impurity; if all the elements belong to a single class, it can be called pure. The degree of the Gini Index varies between 0 and 1. A Gini Index of 0 denotes that all elements belong to a certain class or only one class exists (pure). A Gini Index of 1 denotes that the elements are randomly distributed across various classes (impure).

Gini Index is expressed with the following equation:

![]()

Where:

is the squared probability of class

is the squared probability of class  in a node.

in a node.

6.2 Assumptions

- In the beginning, the whole training set is considered the root.

- Feature values are preferred to be categorical.

- Records are distributed recursively based on attribute values.

6.3 Implementation

We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Decision Tree Classifier'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_DecTree = model_dictionary['Decision Tree Classifier'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Decision Tree Classifier',

model_dictionary['Decision Tree Classifier'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_DecTree)

# Define model score

score_DecTree = model_score(model_dictionary['Decision Tree Classifier'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_DecTree = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_DecTree)

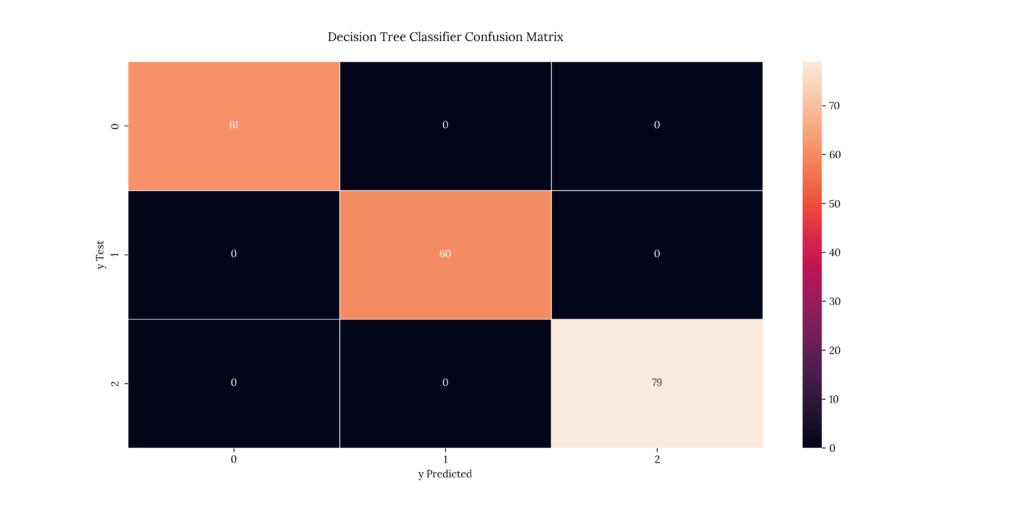

print(score_DecTree)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 100% accuracy:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| macro avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

Output

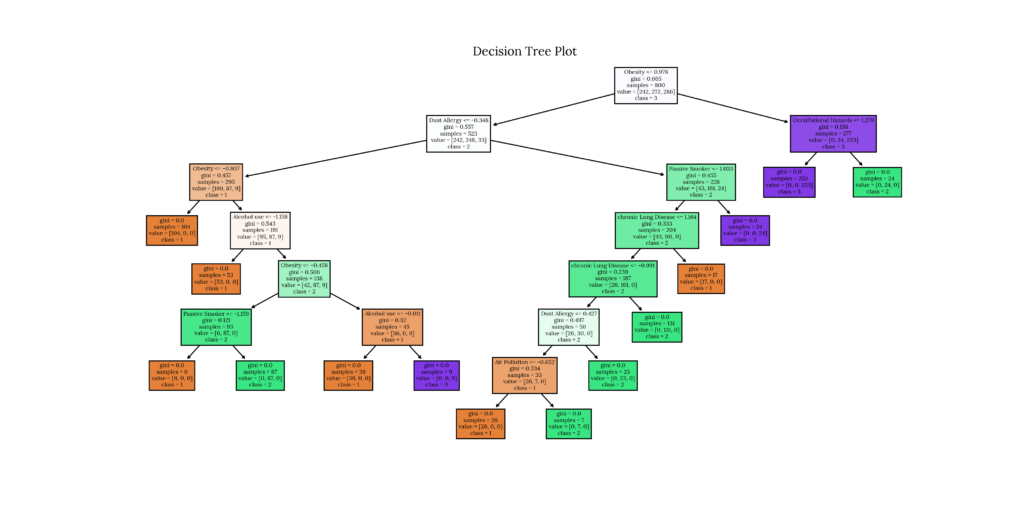

1.0The interesting thing about Decision Trees is that we can visualize them using multiple methods.

We can display a simple text representation:

Code

# Text Representation

DecTree_text_rep = tree.export_text(model_dictionary['Decision Tree Classifier'])

print(DecTree_text_rep)Output

|--- feature_7 <= 0.99

| |--- feature_2 <= -1.29

| | |--- feature_6 <= 0.50

| | | |--- class: 1

| | |--- feature_6 > 0.50

| | | |--- class: 3

| |--- feature_2 > -1.29

| | |--- feature_9 <= 1.03

| | | |--- feature_1 <= -0.00

| | | | |--- feature_7 <= -0.89

| | | | | |--- feature_1 <= -1.16

| | | | | | |--- feature_3 <= -0.63

| | | | | | | |--- class: 2

| | | | | | |--- feature_3 > -0.63

| | | | | | | |--- class: 1

| | | | | |--- feature_1 > -1.16

| | | | | | |--- class: 1

| | | | |--- feature_7 > -0.89

| | | | | |--- feature_6 <= -0.42

| | | | | | |--- feature_1 <= -0.77

| | | | | | | |--- feature_0 <= -0.14

| | | | | | | | |--- feature_1 <= -1.16

| | | | | | | | | |--- feature_7 <= -0.42

| | | | | | | | | | |--- class: 1

| | | | | | | | | |--- feature_7 > -0.42

| | | | | | | | | | |--- class: 2

| | | | | | | | |--- feature_1 > -1.16

| | | | | | | | | |--- class: 2

| | | | | | | |--- feature_0 > -0.14

| | | | | | | | |--- class: 1

| | | | | | |--- feature_1 > -0.77

| | | | | | | |--- feature_6 <= -0.89

| | | | | | | | |--- class: 1

| | | | | | | |--- feature_6 > -0.89

| | | | | | | | |--- class: 2

| | | | | |--- feature_6 > -0.42

| | | | | | |--- feature_7 <= 0.28

| | | | | | | |--- class: 1

| | | | | | |--- feature_7 > 0.28

| | | | | | | |--- class: 2

| | | |--- feature_1 > -0.00

| | | | |--- feature_5 <= 1.17

| | | | | |--- class: 2

| | | | |--- feature_5 > 1.17

| | | | | |--- class: 1

| | |--- feature_9 > 1.03

| | | |--- class: 3

|--- feature_7 > 0.99

| |--- feature_0 <= -0.63

| | |--- class: 2

| |--- feature_0 > -0.63

| | |--- class: 3We can also plot the tree using plot_tree:

Code

# Tree plot using plot_tree

fig = plt.figure('Decision Tree plot_tree')

tree.plot_tree(model_dictionary['Decision Tree Classifier'],

feature_names=df_x.columns,

class_names=df_y['Level'].astype('str'),

filled=True)

plt.title('Decision Tree Plot')

plt.savefig('plots/' + 'Decision Tree Classifier_Decision Tree_tp.png', format = 'png', dpi = 300, transparent = True)

plt.close()Output

7. Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method for classification, regression and other methods. It works by constructing a multitude of decision trees at training time; the output of the random forest is the class selected by most trees.

7.1 Mathematical intuition overview

Given a training set ![]() with responses

with responses ![]() bagging repeatedly (B times) selects a random sample with replacement of the training set and fits trees to these samples.

bagging repeatedly (B times) selects a random sample with replacement of the training set and fits trees to these samples.

After training, predictions for unseen samples ![]() can be made by averaging the predictions from all the individual regression trees on

can be made by averaging the predictions from all the individual regression trees on ![]() or by taking the majority vote from the set of trees.

or by taking the majority vote from the set of trees.

We can also include a measure of the uncertainty of the prediction calculating the standard deviation of the predictions from all the individual regression trees on ![]() .

.

7.2 Assumptions

- It inherits assumptions from the decision tree model.

- There should be some actual values in the feature variables of the dataset, which will give the classifier a better chance to predict accurate results.

- The predictions from each tree must have very low correlations.

7.3 Implementation

We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Random Forest Classifier'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_RandomFor = model_dictionary['Random Forest Classifier'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Random Forest Classifier',

model_dictionary['Random Forest Classifier'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_RandomFor)

# Define model score

score_RandomFor = model_score(model_dictionary['Random Forest Classifier'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_RandomFor = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_RandomFor)

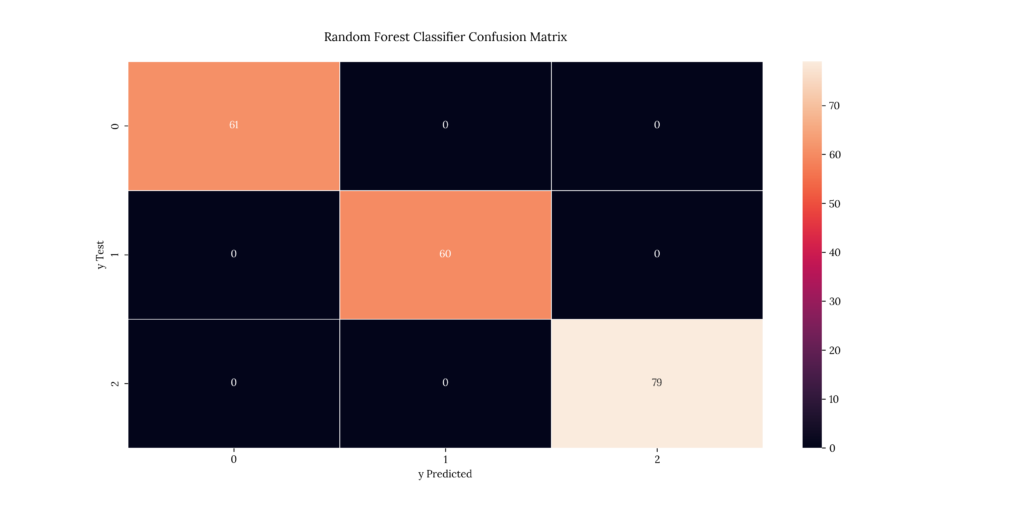

print(score_RandomFor)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 100% accuracy:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| macro avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

Output

1.08. Nonlinear Support Vector Machine

Support Vector Machines (SVM) are a class of supervised models originally developed for linear applications, although a nonlinear implementation using nonlinear Kernels was also developed; the resulting algorithm is similar, except that every dot product is replaced by a nonlinear kernel function.

8.1 Mathematical intuition overview

The SVM model amounts to minimizing an expression of the following form:

![]()

Where:

is the loss function.

is the loss function. is the regularization.

is the regularization.

With the different nonlinear Kernels being:

- Polynomial homogeneous (when

, this becomes the linear kernel):

, this becomes the linear kernel):

- Polynomial homogeneous:

- Gaussian Radial Basis Function (RBF):

, for

, for

- Sigmoid function:

, for some

, for some  and

and

8.2 Assumptions

There are no particular assumptions for this model. If we scale our variables, we might increase its performance, but it is not required.

8.3 Implementation

For this part, we’ll be using three different approaches; we mentioned that Support Vector Machines are fit for linear applications, although we can use nonlinear Kernels to fit nonlinear data.

There are two particular Kernels we will implement:

- Polynomial Kernel: As its name suggests, this Kernel represents the similarity of vectors in a feature space over polynomials of the original variables. We can select the order of the polynomial as a parameter.

- Radial Basis Function Kernel: This Kernel is the most generalized form of kernelization and is one of the most widely used in SVM due to its similarity to the Gaussian distribution.

We can start by fitting our models to our data:

Code

# Train models

model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)

model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Polynomial Kernel'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)

model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Radial Kernel'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained models:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_SVM = model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier'].predict(test_Sx)

y_predicted_SVMp = model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Polynomial Kernel'].predict(test_Sx)

y_predicted_SVMr = model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Radial Kernel'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our models using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Support Vector Classifier',

model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_SVM)

cm_plot('Support Vector Classifier Polynomial Kernel',

model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Polynomial Kernel'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_SVMp)

cm_plot('Support Vector Classifier Radial Kernel',

model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Radial Kernel'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_SVMr)

# Define model score

score_SVM = model_score(model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

score_SVMp = model_score(model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Polynomial Kernel'], test_Sx, test_Sy)

score_SVMr = model_score(model_dictionary['Support Vector Classifier Radial Kernel'], test_Sx, test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_SVM = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_SVM)

report_SVMp = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_SVMp)

report_SVMr = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_SVMr)

print(score_SVM)

print(score_SVMp)

print(score_SVMr)If we look at our results, we can see that we get the following accuracies:

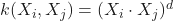

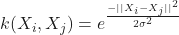

- Linear SVM: 88.5%

- Polynomial SVM, 8th degree: 100%

- Radial Kernel: 100%

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.780822 | 0.934426 | 0.850746 | 61 |

| 2 | 0.888889 | 0.666667 | 0.761905 | 60 |

| 3 | 0.95122 | 0.987342 | 0.968944 | 79 |

| accuracy | 0.875 | 0.875 | 0.875 | 0.875 |

| macro avg | 0.873643 | 0.862812 | 0.860532 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 0.880549 | 0.875 | 0.870782 | 200 |

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| macro avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| macro avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

Output

0.885

1.0

1.09. K-Nearest Neighbors

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) is a non-parametric, supervised learning classifier which uses proximity to classify and group data points. A class label is assigned based on a majority vote i.e. the label that is most frequently represented around a given data point is used. The KNN model chooses ![]() nearest points by calculating distances using different metrics and calculating an average to make a prediction.

nearest points by calculating distances using different metrics and calculating an average to make a prediction.

9.1 Mathematical intuition overview

Several distance metrics can be used:

9.1.1 Euclidean distance

This is the most one, and it is limited to real-valued vectors. It measures a straight line between two points: We can then predict some values using our trained models:

![]()

9.1.2 Manhattan distance

It is also referred to as taxicab distance or city block distance as it is commonly visualized using a grid:

![]()

9.1.3 Minkowski distance

This metric is the generalized form of Euclidean and Manhattan distance metrics. Euclidean distance takes ![]() , while Manhattan distance takes

, while Manhattan distance takes ![]()

![]()

9.1.4 Hamming distance

This technique is typically used with Boolean or string vectors. Interestingly, it’s also used in information theory as a way to measure the distance between two strings of equal length:

![]()

- If

,

,  ,

, - If

,

,

9.2 Assumptions

- Items close together in the data set are typically similar

9.3 Implementation

We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_KNN = model_dictionary['K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier',

model_dictionary['K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_KNN)

# Define model score

score_KNN = model_score(model_dictionary['K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_KNN = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_KNN)

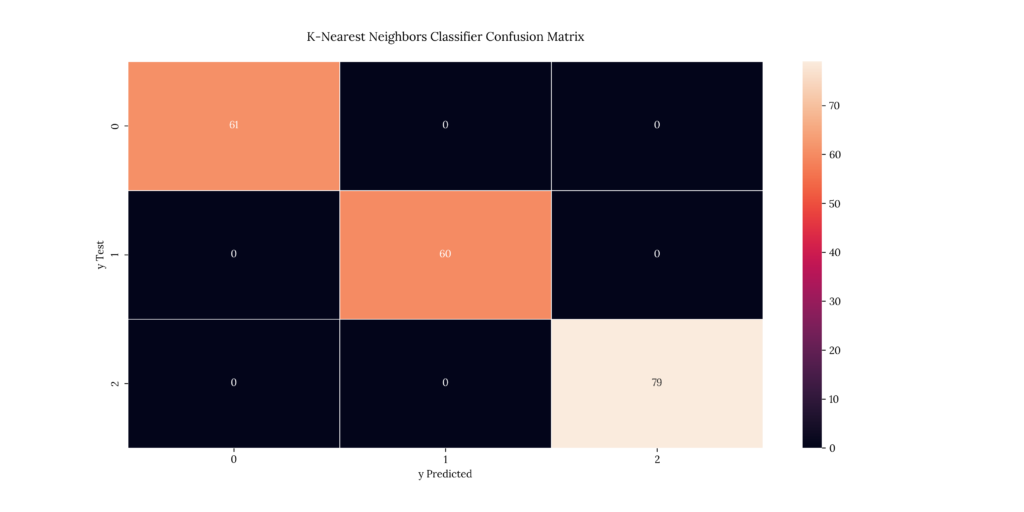

print(score_KNN)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with an 100% accuracy:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| macro avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

Output

1.011. Gaussian Naïve Bayes

Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB) is a probabilistic machine learning algorithm based on the Bayes’ Theorem. It is the extension of the Naïve Bayes algorithm, and as its name suggests, it approximates class-conditional distributions as a Gaussian distribution, with a mean ![]() and a standard deviation

and a standard deviation ![]() .

.

11.1 Mathematical intuition overview

We can start with the Bayes’ Theorem:

![]()

Where:

is the probability of

is the probability of  occurring.

occurring. is the probability of

is the probability of  occurring.

occurring. is the probability of

is the probability of  given

given  .

. is the probability of

is the probability of  given

given  .

. is the probability of

is the probability of  and

and  occurring.

occurring.

We can then translate the formula above to the Gaussian Naïve Bayes equation:

![]()

We can see that the form of this equation is almost identical to the Gaussian distribution density function. The main difference is that in the first one, we’re defining our function as a probability function, while in the latter, we’re defining it as a density function:

![]()

11.2 Assumptions

- Features are independent (hence Naïve).

- Class-conditional densities are normally distributed.

11.3 Implementation

Since we are using the Gaussian variant of the model, we will use the normally-approximated values we generated earlier. We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier'].fit(train_Gx, train_Gy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_GNB = model_dictionary['Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier'].predict(test_Gx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier',

model_dictionary['Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier'],

test_Gy,

y_predicted_GNB)

# Define model score

score_GNB = model_score(model_dictionary['Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier'],

test_Gx,

test_Gy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_GNB = classification_rep(test_Gy,

y_predicted_GNB)

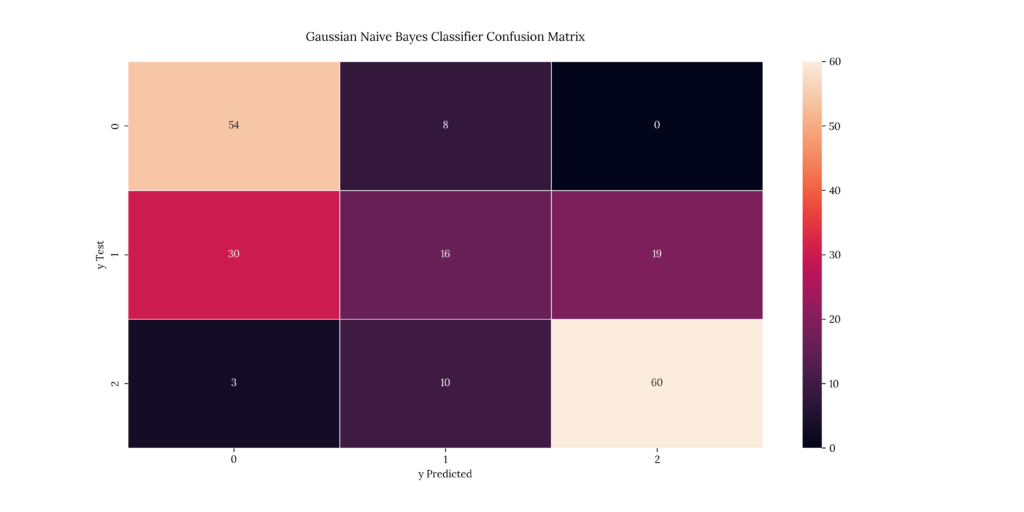

print(score_GNB)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 60.5% accuracy. This is the lowest score we’ve gotten so far:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.62069 | 0.870968 | 0.724832 | 62 |

| 2 | 0.470588 | 0.246154 | 0.323232 | 65 |

| 3 | 0.759494 | 0.821918 | 0.789474 | 73 |

| accuracy | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| macro avg | 0.616924 | 0.646346 | 0.612513 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 0.62257 | 0.65 | 0.617906 | 200 |

Output

0.60512. Bernoulli Naïve Bayes

Bernoulli Naïve Bayes (BNB) is similar to Gaussian Naïve Bayes in that it also uses Bayes’ Theorem as its foundation. The difference is that Bernoulli Naïve Bayes approximates class-conditional distributions as a Bernoulli distribution. This fact makes this variation more appropriate for discrete random variables instead of continuous ones.

12.1 Mathematical intuition overview

Since we already went over Bayes’ Theorem, we can start by defining the Bernoulli distribution function:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com p(x) =P[X=x] =\begin{cases}p & \text{if $x = 1$}, \\q=1 - p & \text{if $x = 0$}.\end{cases}](https://pabloagn.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c4cdd1e55d72e4f99e13d909ade8d0b3_l3.png)

From the above, we can then define the Bernoulli Naïve Bayes Classifier:

![]()

12.2 Assumptions

- The attributes are independent of each other and do not affect each other’s performance (hence Naïve).

- All of the features are given equal importance.

12.3 Implementation

We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Bernoulli Naive Bayes Classifier'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_BNB = model_dictionary['Bernoulli Naive Bayes Classifier'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Bernoulli Naive Bayes Classifier',

model_dictionary['Bernoulli Naive Bayes Classifier'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_BNB)

# Define model score

score_BNB = model_score(model_dictionary['Bernoulli Naive Bayes Classifier'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_BNB = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_BNB)

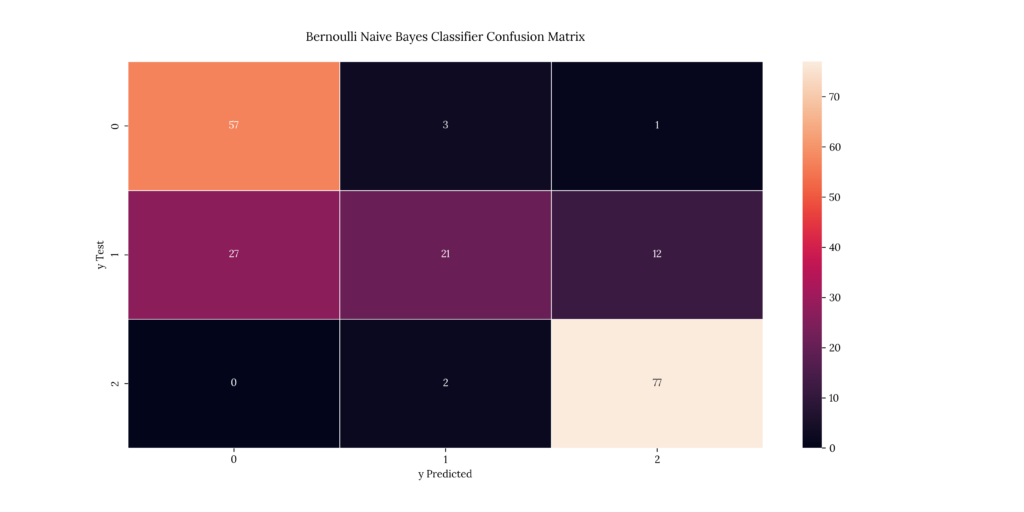

print(score_BNB)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 77.5% accuracy:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.678571 | 0.934426 | 0.786207 | 61 |

| 2 | 0.807692 | 0.35 | 0.488372 | 60 |

| 3 | 0.855556 | 0.974684 | 0.911243 | 79 |

| accuracy | 0.775 | 0.775 | 0.775 | 0.775 |

| macro avg | 0.780606 | 0.753037 | 0.728607 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 0.787216 | 0.775 | 0.746246 | 200 |

Output

0.77513. Stochastic Gradient Descent

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is an optimization method. It can be used in conjunction with other Machine Learning algorithms.

In general, gradient descent is used to minimize a cost function. There are three main types:

- Batch gradient descent

- Mini-batch gradient descent

- Stochastic gradient descent

Stochastic Gradient Descent computes the gradient by calculating the derivative of the loss of a single random data point rather than all of the data points (hence the name, stochastic). It then finds a minimum by taking steps. What makes it different from other optimization methods is its efficiency, i.e. it only uses one single random point to calculate the derivative.

The Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier is a linear classification method with SGD training.

13.1 Mathematical intuition overview

The SGD gradient function can be expressed as follows:

![]()

Where:

is a given training example.

is a given training example. is a given label.

is a given label. is the true gradient of

is the true gradient of

is the approximation of the true gradient

is the approximation of the true gradient  at time

at time  by a gradient at a single sample.

by a gradient at a single sample. is the position of the previous step.

is the position of the previous step.

As the algorithm sweeps through the training set, it performs the above update for each training sample. Several passes can be made over the training set until the algorithm converges.

13.2 Assumptions

- The errors at each point in the parameter space are additive

- The expected value of the observation picked randomly is a subgradient of the function at point

.

.

13.3 Implementation

For this example, we’ll use a Logistic Regressor with SGD training. We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Stochastic Gradient Descent'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_SGD = model_dictionary['Stochastic Gradient Descent'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Stochastic Gradient Descent',

model_dictionary['Stochastic Gradient Descent'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_SGD)

# Define model score

score_SGD = model_score(model_dictionary['Stochastic Gradient Descent'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_SGD = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_SGD)

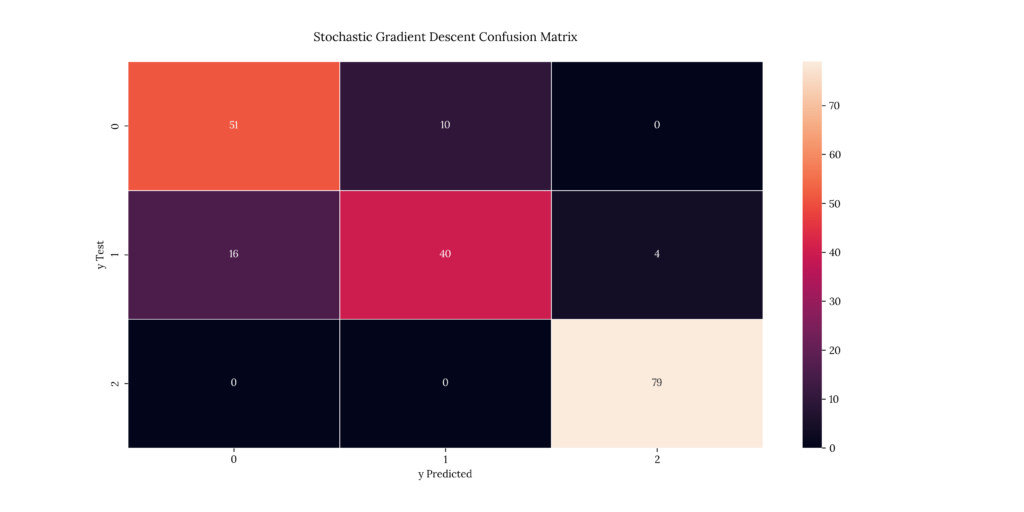

print(score_SGD)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with an 80.5% accuracy:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.761194 | 0.836066 | 0.796875 | 61 |

| 2 | 0.8 | 0.666667 | 0.727273 | 60 |

| 3 | 0.951807 | 1 | 0.975309 | 79 |

| accuracy | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| macro avg | 0.837667 | 0.834244 | 0.833152 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 0.848128 | 0.85 | 0.846476 | 200 |

Output

0.8514. Gradient Boosting

Gradient Boosting (GBM) is a machine learning technique used in regression and classification tasks to create a stronger model using an ensemble of weaker models. The objective of Gradient Boosting classifiers is to minimize the loss or the difference between the actual class value of the training example and the predicted class value. As with other classifiers, GBM depends on a loss function, which can be customized to improve performance.

Gradient Boosting Classifiers consist of three main parts:

- The weak model, usually a Decision Tree

- The additive component

- A loss function that is to be optimized

The main problem with Gradient Boosting is the potential of overfitting the model. We know that perfect training scores will lead to this phenomenon. This can be overcome by setting different regularization methods such as tree constraints, shrinkage and penalized learning.

14.1 Mathematical intuition overview

We can generalize a Gradient-Boosted Decision Tree model.

We can initialize our model with a constant loss function:

![]()

We can then compute the residuals:

![]()

We can then train our Decision Tree with features ![]() against

against ![]() and create terminal node regressions

and create terminal node regressions ![]() .

.

Next, we can compute a ![]() which minimizes our loss function on each terminal node:

which minimizes our loss function on each terminal node:

![]()

Finally, we can recompute the model with our new ![]() :

:

![]()

Where:

is the residual or gradient of our loss function.

is the residual or gradient of our loss function. is our first iteration.

is our first iteration. is the updated prediction.

is the updated prediction. is the previous prediction.

is the previous prediction. is the learning rate between 0 and 1.

is the learning rate between 0 and 1. is the value which minimizes the loss function on each terminal node.

is the value which minimizes the loss function on each terminal node. is the terminal node.

is the terminal node.

14.2 Assumptions

- The sum of its residuals is 0, i.e. the residuals should be spread randomly around zero.

14.3 Implementation

For this example, we’ll use a Gradient Boosting Classifier. We will leave parameters as default (100 estimators), although these can be fine-tuned. We can start by fitting our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Gradient Boosting Classifier'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_GBC = model_dictionary['Gradient Boosting Classifier'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

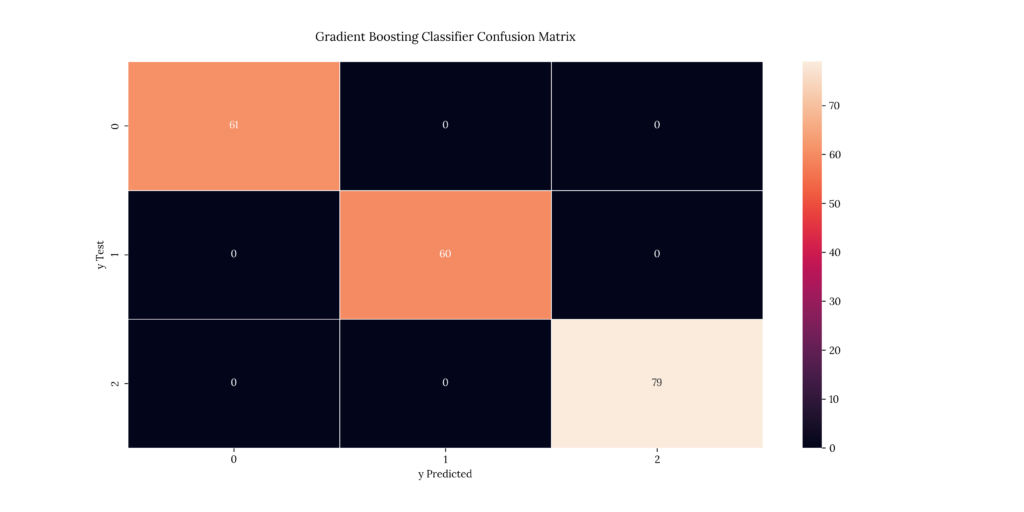

cm_plot('Gradient Boosting Classifier',

model_dictionary['Gradient Boosting Classifier'],

test_Sy,

y_predicted_GBC)

# Define model score

score_GBC = model_score(model_dictionary['Gradient Boosting Classifier'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_GBC = classification_rep(test_Sy,

y_predicted_GBC)

print(score_GBC)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 100% accuracy:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| macro avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

Output

1.015. Extreme Gradient Boosting

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a more regularized form of the previous Gradient Boosting technique. This means that it controls overfitting better, resulting in better performance; as opposed to GBM, XGBoost uses advanced regularization (L1 & L2), which improves model generalization capabilities. It also has faster training capabilities and can be parallelized across clusters, reducing training times.

Some other differences between XGBoost over GBM are:

- The use of sparse matrices with sparsity-aware algorithms.

- Improved data structures for better processor cache utilization which makes it faster.

We will skip the mathematical intuition for XGBoost since it’s extensive and similar to its GBM cousin.

15.1 Assumptions

- Encoded integer values for each input variable have an ordinal relationship.

- The data may not be complete (can handle sparsity)

15.2 Implementation

We’ll use a different library called XGBoost for this implementation. Apart from the advantages of the mathematical treatment, XGBoost is written in C++, making it comparatively faster than other Gradient Boosting libraries. Also, XGBoost was specifically designed to support parallelization onto GPUs and computer networks. These make this library extremely powerful when handling extensive data sets.

Before we can start, we will need to re-encode our labels since XGBoost requires our values to start from 0 and not 1:

Code

# Re-encode labels

train_Sy_XGBC = LabelEncoder().fit_transform(train_Sy)

test_Sy_XGBC = LabelEncoder().fit_transform(test_Sy)We will then fit our model to our data:

Code

# Train model

model_dictionary['Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier'].fit(train_Sx, train_Sy_XGBC)We can then predict some values using our trained model:

Code

# Predict

y_predicted_XGBC = model_dictionary['Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier'].predict(test_Sx)We can finally evaluate our model using the metrics we defined earlier:

Code

# Evaluate the model and collect the scores

cm_plot('Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier',

model_dictionary['Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier'],

test_Sy_XGBC,

y_predicted_XGBC)

# Define model score

score_XGBC = model_score(model_dictionary['Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier'],

test_Sx,

test_Sy_XGBC)

# Define Classification Report Function

report_XGBC = classification_rep(test_Sy_XGBC,

y_predicted_XGBC)

print(score_XGBC)If we take a look at our results, we can see that it predicted with a 100% accuracy:

Output

Output

| X | precision | recall | f1-score | support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 79 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| macro avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

| weighted avg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 200 |

Output

Output

1.016. Deep Neural Networks

Deep Neural Networks are simply Neural Networks containing at least two interconnected layers of neurons. Its functioning and the theory behind them are somewhat different from what we’ve seen so far. Also, they belong to another branch of Artificial Intelligence called Deep Learning, which is itself a subgroup of Neural Networks. The model that would assimilate more (in a sense ) is Decision Trees, although even they process data differently.

Neural Networks were created based on how actual neurons work (in a very general way); they are comprised of node layers containing an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each node connects to another and has an associated weight and threshold. These parameters define the signal intensity from one neuron to another; if the output of a given individual node is above the specified threshold value, that node is activated, sending a signal to the next layer of the network; else, the signal doesn’t pass through.

Although Deep Neural Networks can achieve complex classification tasks, there are some significant disadvantages:

- It takes time and domain knowledge to fine-tune a Neural Network.

- They’re sensitive to data inputs.

- They are computationally expensive, making them challenging to deploy in a production environment.

- Their hidden layers work as black boxes, making them hard to understand or debug.

- Most of the time, they require more data to return accurate results.

- They rely more on training data, potentially leading to overfitting.

A simpler alternative, such as the Decision Tree Classifier, often gives better accuracy without all the disadvantages above.

Apart from all the points mentioned, there are also significant advantages:

- They can perform unsupervised learning.

- They have good fault tolerance, meaning the output is not affected by the corruption of one or more than one cell.

- They have distributed memory capabilities.

16.1 Mathematical intuition overview

As we have mentioned, a Neural Network works by propagating signals depending on the weight and threshold of each neuron.

The most basic Neural Network is called perceptron and consists of ![]() number of inputs, one neuron, and one output.

number of inputs, one neuron, and one output.

A perceptron’s forward propagation starts by weighting each input and adding all the multiplied values. Weights decide how much influence the given input will have on the neuron’s output:

![]()

Where:

is a vector of inputs.

is a vector of inputs. is a vector of weights.

is a vector of weights. is the dot product between

is the dot product between  and

and  .

.

Then, a bias is added to the summation calculated before:

![]()

Where:

is the bias

is the bias

Finally, we pass ![]() to a non-linear activation function. Perceptrons have binary step functions as their activation functions. This is the most simple type of function; it produces a binary output:

to a non-linear activation function. Perceptrons have binary step functions as their activation functions. This is the most simple type of function; it produces a binary output:

A perceptron is the simplest case, and of course, the more layers we have, the more complex the mathematical derivation gets. Also, more complex and appropriate activation functions are available since the binary activation functions present important disadvantages.

The theory behind Deep Neural Networks is extensive and complex, so we will not explain each step in detail; instead, we will stick with a general description of what is being done. A rigorous & exhaustive explanation of these models can be found in Philipp Christian Petersen’s Neural Network Theory.

16.2 Assumptions

- Artificial Neurons are arranged in layers, which are sequentially arranged.

- Neurons within the same layer do not interact or communicate with each other.

- All inputs enter the network through the input layer and pass through the output layer.

- All hidden layers at the same level should have the same activation function.

- Artificial neurons at consecutive layers are densely connected.

- Every inter-connected neural network has its weight and bias associated with it.

16.3 Implementation

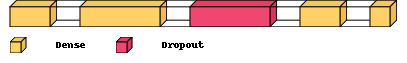

Deep Neural Networks require a different treatment than we’ve already seen. For this case, a simpler 5-layer Sequential model will suffice. The first thing we’ll need to do is define which model we will use.

A Sequential Neural Network passes on the data and flows in sequential order from top to bottom until the data reaches the end of the model.

We can start by making defining our model:

Code

# Define model

DNN = model_dictionary['Sequential Deep Neural Network']Then, we can add the first two dense layers, both using ![]() (Rectified Linear Unit) activation functions:

(Rectified Linear Unit) activation functions:

Code

# Add first two layers using ReLU activation function

DNN.add(Dense(8, activation = "relu", input_dim = train_Sx.shape[1]))

DNN.add(Dense(16, activation = "relu"))Next, we will add a ![]() regularization layer. A dropout layer randomly sets input units to 0 with a frequency rate between 0 and 1 at each step during training time. This helps prevent overfitting:

regularization layer. A dropout layer randomly sets input units to 0 with a frequency rate between 0 and 1 at each step during training time. This helps prevent overfitting:

Code

# Add Dropout regularization layer

DNN.add(Dropout(0.1))We will conclude with our model by adding one last dense ![]() activation layer and one dense

activation layer and one dense ![]() (normalized exponential function) activation layer, which will serve as the activation function for our output layer. The

(normalized exponential function) activation layer, which will serve as the activation function for our output layer. The ![]() activation function converts an input vector of real values to an output vector that can be interpreted as categorical probabilities. It is specially used for categorical variables:

activation function converts an input vector of real values to an output vector that can be interpreted as categorical probabilities. It is specially used for categorical variables:

Code

# Add third layer using ReLU, and output layer using softmax

DNN.add(Dense(8, activation = "relu"))

DNN.add(Dense(3, activation = "softmax"))We will finally compile our model using ![]() as our loss function and

as our loss function and ![]() (adaptive moment estimation) as our optimization function. The

(adaptive moment estimation) as our optimization function. The ![]() loss, also called

loss, also called ![]() , is a

, is a ![]() activation plus a

activation plus a ![]() . It is used for categorical multi-class classification and accepts labels as one-hot encoded. The

. It is used for categorical multi-class classification and accepts labels as one-hot encoded. The ![]() optimizer is an extension to stochastic gradient descent:

optimizer is an extension to stochastic gradient descent:

Code

# Compile our model

DNN.compile(optimizer = "adam", loss = "categorical_crossentropy", metrics = ["accuracy"])Below is a summary of our Deep Neural Network architecture:

- Layer 1:

- Dense with 8 nodes.

- Serves as our input layer as well as our first hidden layer.

- Its shape is given by the feature DataFrame dimensions.

- Uses

activation function.

activation function.

- Layer 2:

- Dense with 16 nodes.

- Serves as our second hidden layer.

- Uses

activation function.

activation function.

- Layer 3:

- Dropout with

, meaning 1 in 10 inputs will be randomly excluded from each update cycle.

, meaning 1 in 10 inputs will be randomly excluded from each update cycle. - Serves as our third hidden layer.

- Dropout with

- Layer 4:

- Dense with 8 nodes.

- Serves as our fourth hidden layer.

- Uses

activation function.

activation function.

- Layer 5:

- Dense with 3 nodes, meaning 3 categorical outputs to be predicted.

- Uses

activation function

activation function

- Compiled model:

- Is Sequential.

- Uses the

optimizer.

optimizer. - Uses a

loss function.

loss function.

Before training our model, we will need to re-encode & dummify our labels:

Code

# Re-encode & dummify labels

df_y_D = LabelEncoder().fit_transform(df_y)

df_y_D = pd.get_dummies(df_y_D)We will then fit our model:

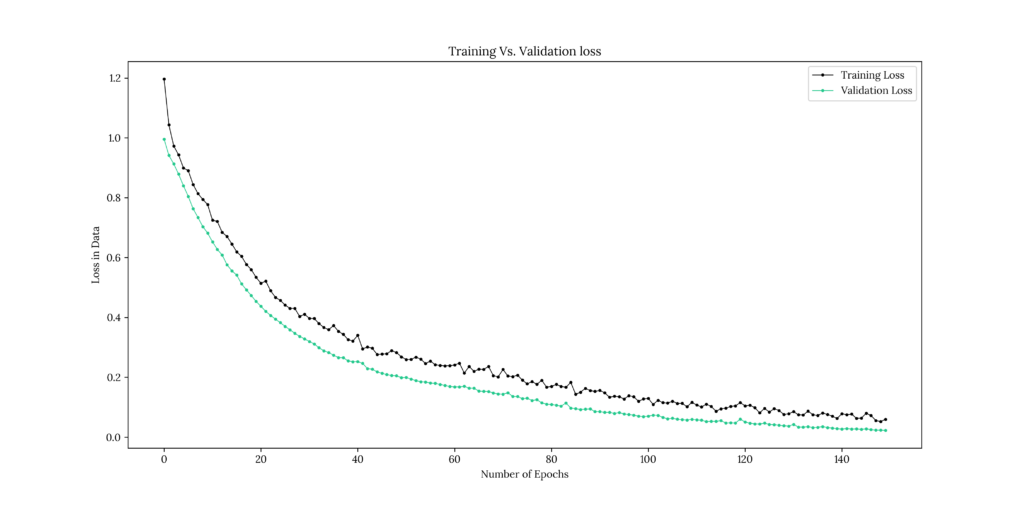

Code

# Fit our compiled model

DNN_Fit = DNN.fit(df_x, df_y_D, epochs = 150, validation_split = 0.3)Output

Epoch 1/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 6ms/step - loss: 1.1964 - accuracy: 0.3643 - val_loss: 0.9955 - val_accuracy: 0.3967

Epoch 2/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 1.0430 - accuracy: 0.3871 - val_loss: 0.9412 - val_accuracy: 0.4600

Epoch 3/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.9726 - accuracy: 0.4986 - val_loss: 0.9127 - val_accuracy: 0.5367

Epoch 4/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.9428 - accuracy: 0.5214 - val_loss: 0.8785 - val_accuracy: 0.5733

Epoch 5/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.8994 - accuracy: 0.5729 - val_loss: 0.8400 - val_accuracy: 0.5833

Epoch 6/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.8901 - accuracy: 0.5843 - val_loss: 0.8042 - val_accuracy: 0.6400

Epoch 7/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.8438 - accuracy: 0.6057 - val_loss: 0.7630 - val_accuracy: 0.6500

Epoch 8/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.8136 - accuracy: 0.6471 - val_loss: 0.7340 - val_accuracy: 0.6800

Epoch 9/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.7942 - accuracy: 0.6271 - val_loss: 0.7032 - val_accuracy: 0.7200

Epoch 10/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.7768 - accuracy: 0.6457 - val_loss: 0.6817 - val_accuracy: 0.7067

Epoch 11/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.7246 - accuracy: 0.6871 - val_loss: 0.6524 - val_accuracy: 0.7600

Epoch 12/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.7206 - accuracy: 0.7086 - val_loss: 0.6272 - val_accuracy: 0.7367

Epoch 13/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.6841 - accuracy: 0.7086 - val_loss: 0.6084 - val_accuracy: 0.7700

Epoch 14/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.6706 - accuracy: 0.7171 - val_loss: 0.5760 - val_accuracy: 0.7967

Epoch 15/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.6454 - accuracy: 0.7371 - val_loss: 0.5556 - val_accuracy: 0.8200

Epoch 16/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.6189 - accuracy: 0.7371 - val_loss: 0.5415 - val_accuracy: 0.7967

Epoch 17/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.6040 - accuracy: 0.7500 - val_loss: 0.5121 - val_accuracy: 0.7567

Epoch 18/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.5769 - accuracy: 0.7586 - val_loss: 0.4923 - val_accuracy: 0.8133

Epoch 19/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.5599 - accuracy: 0.7643 - val_loss: 0.4731 - val_accuracy: 0.7833

Epoch 20/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.5339 - accuracy: 0.7757 - val_loss: 0.4536 - val_accuracy: 0.8133

Epoch 21/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.5142 - accuracy: 0.7814 - val_loss: 0.4372 - val_accuracy: 0.8300

Epoch 22/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.5214 - accuracy: 0.7929 - val_loss: 0.4202 - val_accuracy: 0.8767

Epoch 23/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4892 - accuracy: 0.7957 - val_loss: 0.4068 - val_accuracy: 0.7800

Epoch 24/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4669 - accuracy: 0.8071 - val_loss: 0.3943 - val_accuracy: 0.8533

Epoch 25/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4572 - accuracy: 0.8243 - val_loss: 0.3826 - val_accuracy: 0.8400

Epoch 26/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4411 - accuracy: 0.8171 - val_loss: 0.3701 - val_accuracy: 0.7900

Epoch 27/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4304 - accuracy: 0.8314 - val_loss: 0.3587 - val_accuracy: 0.8400

Epoch 28/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4302 - accuracy: 0.8343 - val_loss: 0.3470 - val_accuracy: 0.9033

Epoch 29/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4032 - accuracy: 0.8643 - val_loss: 0.3367 - val_accuracy: 0.9033

Epoch 30/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.4106 - accuracy: 0.8471 - val_loss: 0.3283 - val_accuracy: 0.8533

Epoch 31/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3970 - accuracy: 0.8543 - val_loss: 0.3197 - val_accuracy: 0.8933

Epoch 32/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3964 - accuracy: 0.8414 - val_loss: 0.3114 - val_accuracy: 0.8933

Epoch 33/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3795 - accuracy: 0.8614 - val_loss: 0.2986 - val_accuracy: 0.9300

Epoch 34/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3663 - accuracy: 0.8800 - val_loss: 0.2885 - val_accuracy: 0.9300

Epoch 35/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3590 - accuracy: 0.8786 - val_loss: 0.2829 - val_accuracy: 0.8933

Epoch 36/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3729 - accuracy: 0.8671 - val_loss: 0.2737 - val_accuracy: 0.9300

Epoch 37/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3536 - accuracy: 0.8614 - val_loss: 0.2659 - val_accuracy: 0.9300

Epoch 38/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3436 - accuracy: 0.8700 - val_loss: 0.2655 - val_accuracy: 0.9033

Epoch 39/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3260 - accuracy: 0.8829 - val_loss: 0.2550 - val_accuracy: 0.9300

Epoch 40/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3210 - accuracy: 0.9000 - val_loss: 0.2519 - val_accuracy: 0.9300

Epoch 41/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3401 - accuracy: 0.8714 - val_loss: 0.2525 - val_accuracy: 0.8633

Epoch 42/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2945 - accuracy: 0.8957 - val_loss: 0.2467 - val_accuracy: 0.8633

Epoch 43/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.3014 - accuracy: 0.8900 - val_loss: 0.2291 - val_accuracy: 0.9400

Epoch 44/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2970 - accuracy: 0.8914 - val_loss: 0.2270 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 45/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2764 - accuracy: 0.9029 - val_loss: 0.2181 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 46/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2774 - accuracy: 0.9171 - val_loss: 0.2132 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 47/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2787 - accuracy: 0.9071 - val_loss: 0.2091 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 48/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2893 - accuracy: 0.8971 - val_loss: 0.2058 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 49/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2826 - accuracy: 0.8986 - val_loss: 0.2049 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 50/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2684 - accuracy: 0.9043 - val_loss: 0.1988 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 51/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2594 - accuracy: 0.9186 - val_loss: 0.1996 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 52/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2597 - accuracy: 0.9157 - val_loss: 0.1939 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 53/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2674 - accuracy: 0.9086 - val_loss: 0.1891 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 54/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2608 - accuracy: 0.9129 - val_loss: 0.1852 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 55/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2460 - accuracy: 0.9143 - val_loss: 0.1840 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 56/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2544 - accuracy: 0.9186 - val_loss: 0.1809 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 57/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2419 - accuracy: 0.9200 - val_loss: 0.1799 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 58/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2395 - accuracy: 0.9086 - val_loss: 0.1761 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 59/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2383 - accuracy: 0.9114 - val_loss: 0.1728 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 60/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2389 - accuracy: 0.9114 - val_loss: 0.1691 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 61/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2411 - accuracy: 0.9171 - val_loss: 0.1680 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 62/150

22/22 [==============================] - 0s 2ms/step - loss: 0.2472 - accuracy: 0.9071 - val_loss: 0.1678 - val_accuracy: 0.9600

Epoch 63/150